Introduction

Introduction

The SDG Summit in September 2019 was marked by renewed commitment from world leaders to accelerate progress towards the SDGs. Scientific assessments such as those in the Global Sustainable Development Report identified strategic entry points through which targeted efforts, for example to build sustainable food systems, invest in human well-being or protect the global environmental commons, could lead to positive outcomes that would cascade across many of the SDGs. Although the way ahead appeared steep, stakeholders were energized by the launch of the Decade of Action. Then, only months later, the COVID-19 pandemic unleashed a tsunami of human suffering with far reaching implications on efforts to improve lives and achieve the SDGs. This grim crisis is still unfolding. While it may take months, even years, to know the impacts of the crisis with certainty, the channels through which they occur are already becoming clear, and initial assessments are sobering with enormous losses of lives and livelihoods; and deepening poverty and hunger. If responses are ad-hoc, underfunded and without a view to long-term goals, the consequences of COVID-19 will be deep and long-lasting and risk reversing decades of progress. However, as countries begin to move towards recovery, coherent actions can place the world on a robust trajectory towards achieving sustainable development.

Recent assessments

Eventual impacts will depend on how severe the initial effects are, whether the recovery is gradual or rapid, and on whether we return to the pre-pandemic world or to one that is more sustainable and equitable. Initial assessments already point towards likely outcomes in the short term and alert us to the immense risks of failing to act swiftly and in a coordinated manner. Global GDP is expected to contract sharply in 2020 – estimates range from 3.2 percent to 5.2 per cent- potentially the largest contraction in economic activity since the Great Depression, and far worse than the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. (United Nations, 2020; World Bank, 2020). In 2020 alone, millions (estimates range from around 35 to 60 million) could be pushed into extreme poverty, reversing the declining global trend of the last twenty-plus years (United Nations, 2020; World Bank). Some 1.6 billion people working in the informal sector including the gig economy are estimated to be at risk of losing their livelihoods and many lack access to any form of social protection (ILO, 2020). An additional 10 million of the world’s children could face acute malnutrition, and the number of people facing acute food insecurity could almost double relative to 2019, rising to 265 million (WFP, 2020a; 2020b). School closures have affected over 90 per cent of the world’s student population—1.6 billion children and youth (UNESCO, 2020). Accounting for the inability to access the internet for remote learning, this could result in out-of-school rates in primary education not seen since the mid-1980s (UNDP, 2020). Assessments such as these are especially worrisome as they can translate into life-long deficits, perpetuating inequalities across generations. The overall slowdown in normal economic activity and travel has, however, resulted in a temporary alleviation of some of the pressures on nature. Air quality has improved across the world, and daily global CO2 emissions fell an estimated 17 per cent in early April, relative to mean levels of 2019 (Le Quéré, et al., 2020). Current estimates for 2020 CO2 emissions are 4-7 per cent lower than last year; however, these improvements may turn out to be only transitory with no real impact on climate change unless the recovery from the pandemic also leads to a rapid transition to a low-carbon way of life.

SDG progress: protection during the pandemic

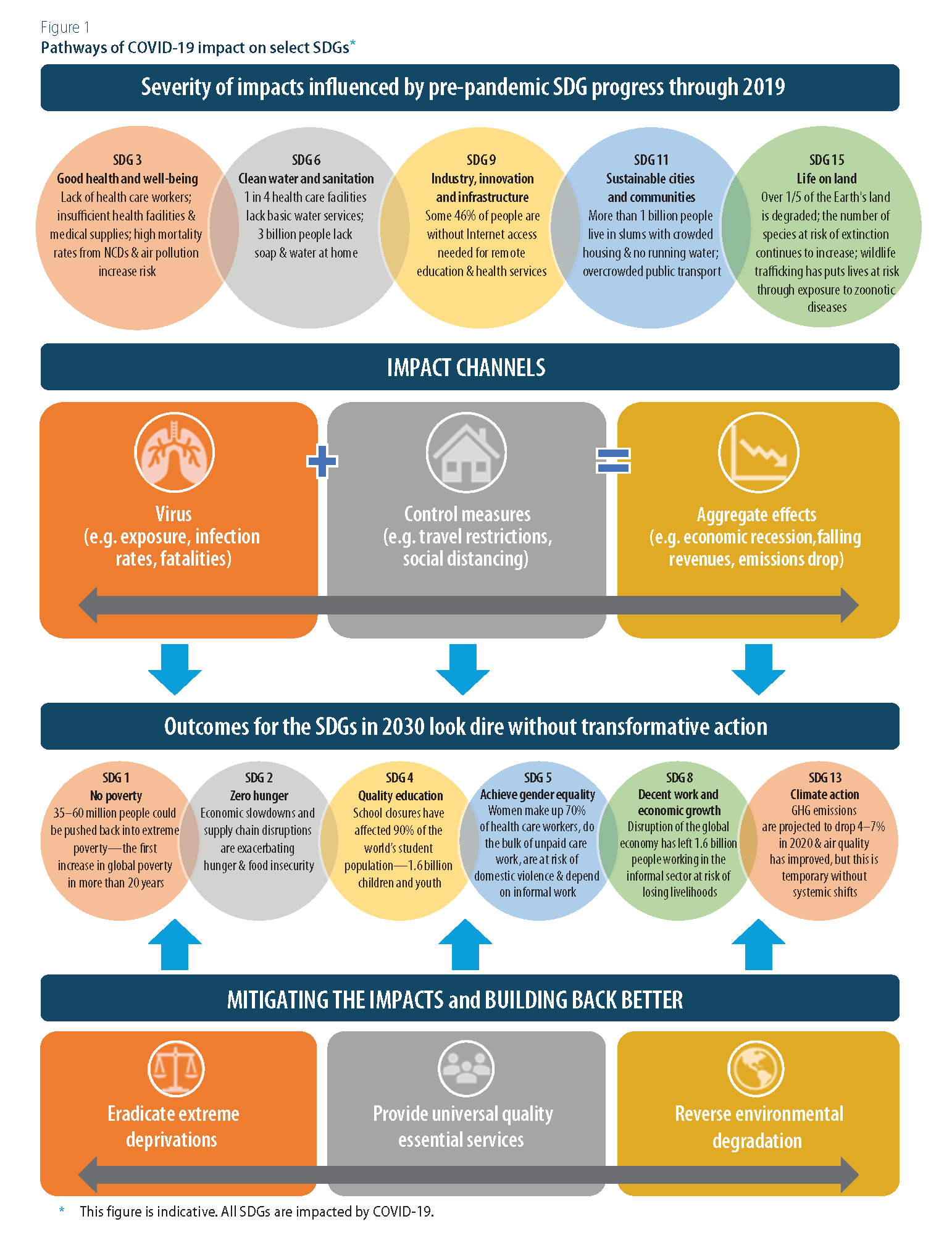

A recovery that puts the world on track to reach the SDGs must begin by considering how the pandemic is likely to affect SDG progress (see Figure 1). There are several channels through which the pandemic affects the well-being of individuals and households—directly due to the health impacts of the virus itself; through crisis response measures like travel restrictions and business closures; and through the aggregated effects of both of these. The disease itself impacts an individual’s health in various ways, some of which are still being understood including in terms of how individual and group characteristics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, living and working conditions) are linked to virus exposure and the severity of illness. Then there are effects arising from crisis response measures such as social distancing and mandated lockdowns. These, too, vary across individuals—lost livelihoods, forced absences from the classroom, foregone vaccinations against other infectious diseases, stresses on mental health, and, for women in particular, a disproportionate increase in the burden of care work as well as greater risk of domestic violence. Finally, there are the aggregate effects across economies and societies—economic recession, falling public revenues and shrinking fiscal space, price increases or quantity disruptions, balance of payments stress due to capital flow reversals, collapses in tourism, decreases in commodity exports and remittances, and more persistent inequalities. Also included are the potential for sustained declines in emission levels and perhaps, in the longer term, collective changes in behaviour and societal norms. These aggregate effects in turn impact individuals, for example shrinking fiscal space could result in poorer public services leading to higher levels of poverty and ill-health; disruptions in the food supply chain could portend poorer nutrition. Notably, the severity of impacts through these channels are influenced by pre-pandemic factors, many of which are at the heart of the SDGs. For example, access to clean water (SDG 6) is a pre-requisite for being able to handwash frequently; living in substandard, unsanitary and overcrowded conditions such as slums (SDG 11) increases the risk of exposure to the virus; and pre-existing health conditions such as non-communicable diseases (SDG 3) tend to worsen disease outcomes. The same is true for the impacts of crisis response measures. Past progress in promoting formal employment (SDG 8); increasing access to quality health care (SDG 3); being covered by social protection floors (SDG 1); ICT availability (SDG 9) that facilitates participation in a virtual classroom to name a few, help mitigate the severity of adverse impacts. At the aggregate level, too, there are distinct benefits from past progress on the SDGs: for example, more diversified economies (SDG 8) may experience less precipitous declines in GDP than those dependent primarily on tourism or petroleum production. This pandemic shows, once again, that the SDGs are tightly interlinked: progress on one goal (or lack thereof) affects other goals. Moreover, the degree of progress along multiple goals and targets is itself likely to contribute to the eventual impacts of the crisis on the SDGs.

Reinforcing the SDGs through crisis response and recovery

While the anticipated outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic are dire, they can be averted by the actions we take now—some of which may already be under way. The aggregate amount of fiscal stimulus across countries is estimated to be USD 9 trillion (Battersby, et al., 2020) and according to a World Bank compilation from late May, 190 countries and territories have planned, introduced or adapted social protection measures in response to COVID-19 (Gentilini, et al., 2020). These responses can contribute to addressing immediate challenges brought on by the pandemic, and also build towards longer-term SDG commitments. Each country will identify tailored solutions to respond to their greatest needs, and efforts at the local level need to be strengthened and supported, but all of these responses must add up to coordinated action that matches the global scale of COVID-19 in order to counter the universal risk of falling short on the SDGs. Three priorities in particular will enable the world to build back better in a unified way. The multilateral system is crucial to supporting their implementation. 1. Maintain past progress made towards eradicating basic deprivations. Backsliding on the progress already made on the SDGs not only imperils prospects for eradicating basic deprivations, it also reduces resilience to other shocks in the future especially for those least able to cope. Maintaining the progress already made must continue to be a priority during the crisis response and beyond—supporting those at immediate risk of poverty, hunger or disease, while facilitating their safe return to work and education, and their access to health care. Such measures must not be exclusively focused on the short term but should also address the root causes of these deprivations, including by the elimination of social or legal barriers for marginalized and disadvantaged groups; and the provision of support that responds directly to their specific needs. No less important is acting to swiftly tackle deprivations where even short-term losses can turn into life-long set-backs—such as preventing the types of limitations throughout the life-course that can be brought about by malnutrition or the denial of education for children. 2. Accelerate the universal provision of quality essential services. The pandemic has exposed the multiple determinants of vulnerability: apart from the basic deprivations indicated above, these now also encompass lack of access to water, sanitation, clean energy and the Internet. Taken together, these constitute a suite of services which, if accessible to all, would help secure well-being, develop resilience and combat inequalities. Guaranteed universal access to services that provide quality healthcare, education and basic income security; as well as to water, sanitation, clean energy and the Internet must therefore become an integral part of the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. Virtually all countries have gaps of one kind or another that need addressing in this regard but it is especially important for multilateral efforts to support the deployment of systems to provide such services in poorer countries. These would continue and build upon initiatives to establish social protection floors, a movement that gained momentum in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. The expansion of services can also generate stable jobs and support the economic empowerment of women or those living in marginalized regions, in themselves valuable outcomes. For example, women make up over 70 per cent of the healthcare workforce, and expanding access to these services can enable their economic empowerment (ILO, 2018). Some of the necessary investments today can come from COVID-19 stimulus packages complemented by technical capacity building and delivery against commitments to provide official development assistance (ODA). Partnerships with the private sector would also be crucial. 3. Reverse course on the degradation of nature. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, several trends related to nature were not even moving in the right direction. These included greenhouse gas emissions, land degradation, biodiversity loss, wildlife trafficking, absolute material footprints, overfishing and the deterioration of coastal waters. Unlike the sudden onset of the pandemic, the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss have built up more slowly. However, these crises are no less destructive to human well-being and they may be even harder to reverse. At the same time, these trends represent the pre-pandemic world—one in which the trade-offs to growth and development were not adequately addressed and to which we cannot afford to return. The pandemic itself reveals the size of the challenge, but also affords a chance to observe—even if for a short period—the plausibility of being able to reverse the degradation of nature. As it stands, an annual decline of 7.6 per cent in greenhouse gas emissions is estimated to be necessary over the next ten years if we are to be on track to limit global warming to 1.50C above pre-industrial levels—even with all of the disruptions due to the crisis, we are unlikely to achieve this in 2020. On the other hand, the economic, social and political costs of taking action may now be lower than before. With oil prices at historic lows and employment in the sector shrinking, steps to initiate a just transition for workers, zero out fuel subsidies and introduce carbon taxes—or increase them where they exist—could set the stage for meeting the most ambitious goals of the Paris Agreement. Historically low interest rates, and complementary investments from stimulus packages can keep costs low for investing in low carbon solutions including those that enable current shifts in behaviour such as tele-working to become more permanent. And a better understanding of the zoonotic origins of many recent disease outbreaks can help support changes in human activity that threaten biodiversity.

Conclusion

The pandemic has generated a pause on ‘business-as-usual’ activities, forcing us to face terrible human outcomes but also encouraging us to envision a realistic way forward towards achieving the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement on climate change. It has also brought to the fore how central the SDGs are, including past progress on the SDGs, for building resilience against shocks and avoiding backslides into poverty. This brief has indicated strategic objectives that are common across countries. Realizing them is within reach but requires both greater coherence and coordination of national actions, as well as a re-invigorated global partnership for development (SDG 17). The United Nations is committed to facilitating a global response that leads towards this end and turns this moment in history into an inflection point for humanity to overcome hardship and transform together toward a more sustainable future.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations