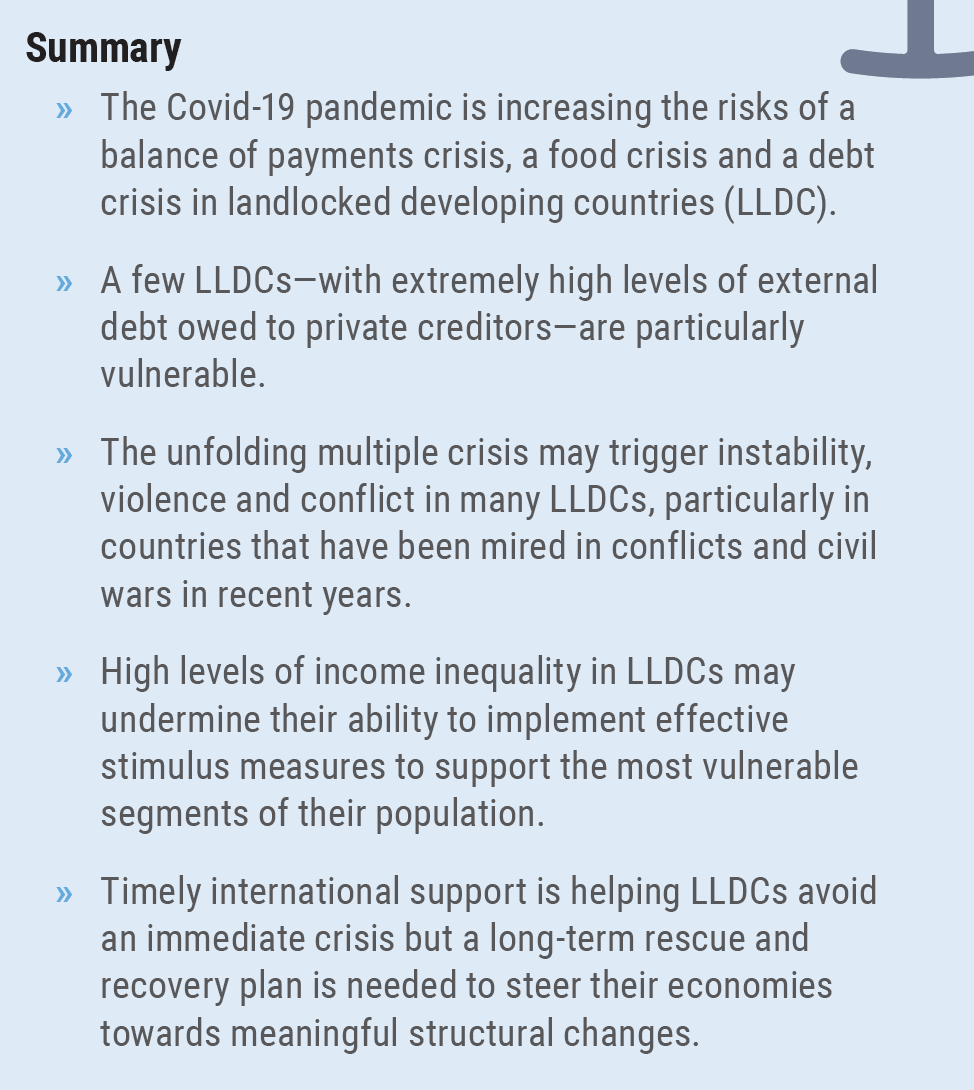

The thirty-two landlocked developing countries (LLDCs)— home to nearly 7 per cent of world population, representing 15 per cent of the membership of the United Nations—are the least economically-integrated countries in the world. As a group, LLDCs are at the fringes of the world economy, accounting for only 0.9 per cent of world gross output and 0.8 per cent of global exports (Figure 1). Seventeen of them also belong to the group of least developed countries (LDCs). These economies are highly heterogeneous, both in terms of the level of development and economic structure. The average per capita income of LLDCs is 2.5 times higher than the LDC average. This average, however, masks the huge dispersion in per capita income among these countries, ranging from $272 for Burundi to $9,813 for Kazakhstan. Constrained by their landlocked status, LLDCs rely heavily on their neighbouring countries’ seaports for the movement of goods and services to and from international markets. Even under ordinary conditions, they face higher trade costs than transit countries, despite continuing international efforts to facilitate their market access.

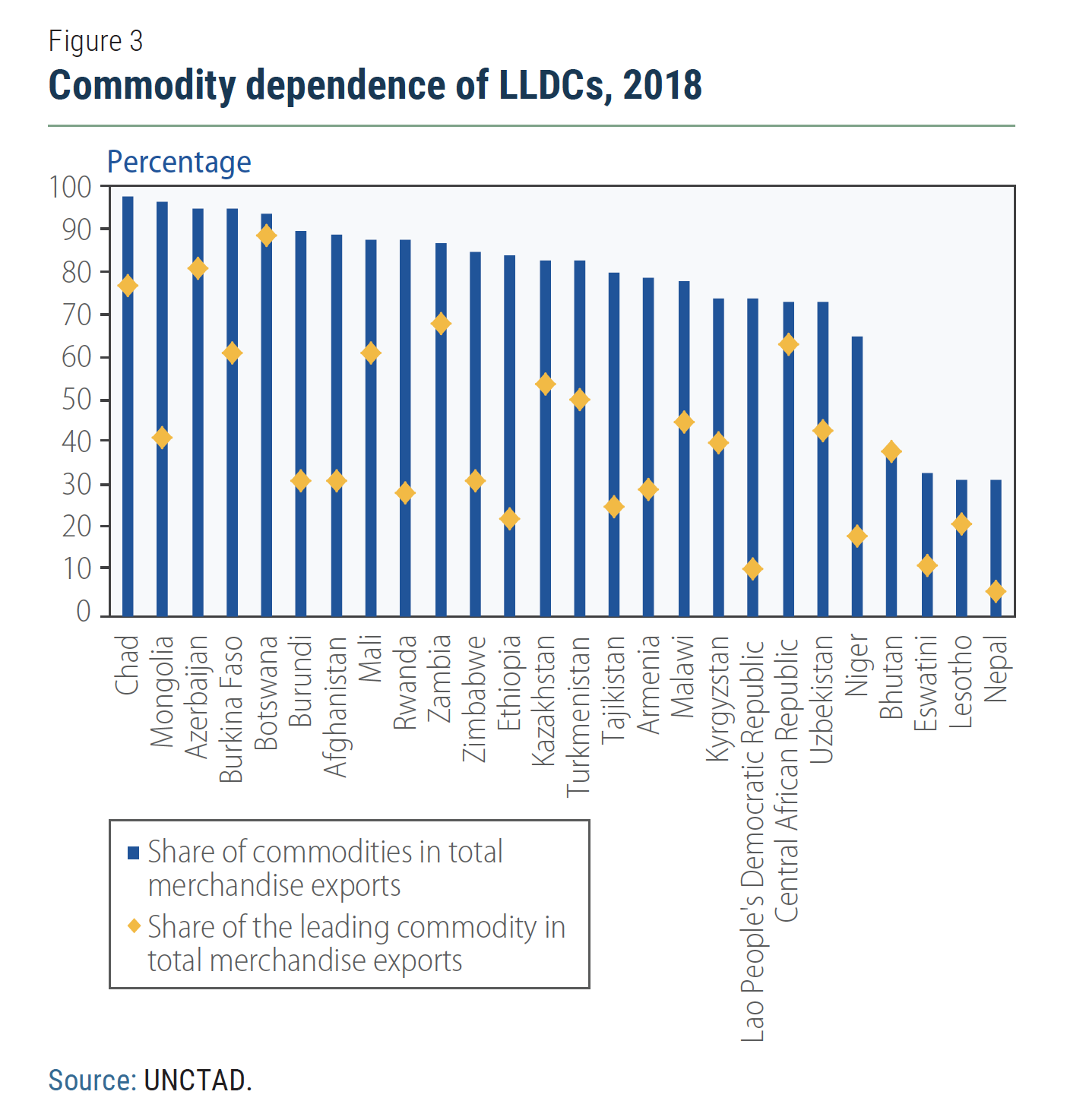

The thirty-two landlocked developing countries (LLDCs)— home to nearly 7 per cent of world population, representing 15 per cent of the membership of the United Nations—are the least economically-integrated countries in the world. As a group, LLDCs are at the fringes of the world economy, accounting for only 0.9 per cent of world gross output and 0.8 per cent of global exports (Figure 1). Seventeen of them also belong to the group of least developed countries (LDCs). These economies are highly heterogeneous, both in terms of the level of development and economic structure. The average per capita income of LLDCs is 2.5 times higher than the LDC average. This average, however, masks the huge dispersion in per capita income among these countries, ranging from $272 for Burundi to $9,813 for Kazakhstan. Constrained by their landlocked status, LLDCs rely heavily on their neighbouring countries’ seaports for the movement of goods and services to and from international markets. Even under ordinary conditions, they face higher trade costs than transit countries, despite continuing international efforts to facilitate their market access.  Many LLDCs are highly dependent on commodities exports, while a few others rely on remittances or tourism as the main source of their foreign exchange earnings, making them highly vulnerable to swings in external flows. Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Mali and South Sudan are mired in protracted civil war and conflicts, while a few other LLDCs—Burundi, Chad, Ethiopia, Nepal, Niger and Uganda experienced violence, instability and conflicts in recent years. Endemic economic and political fragility remains a challenge for many LLDCs, which may flare up again should economic conditions and employment prospects deteriorate quickly. While the COVID-19 pandemic has hit Europe and the United States the hardest, its economic impacts are reverberating in the farthest corners of the world, including in LLDCs. Clearly, the economic consequences of the pandemic will spare no country or country group. Given the high degree of heterogeneity among LLDCs, macroeconomic transmission channels and impacts of COVID-19 will, however, be significantly different across countries.

Many LLDCs are highly dependent on commodities exports, while a few others rely on remittances or tourism as the main source of their foreign exchange earnings, making them highly vulnerable to swings in external flows. Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Mali and South Sudan are mired in protracted civil war and conflicts, while a few other LLDCs—Burundi, Chad, Ethiopia, Nepal, Niger and Uganda experienced violence, instability and conflicts in recent years. Endemic economic and political fragility remains a challenge for many LLDCs, which may flare up again should economic conditions and employment prospects deteriorate quickly. While the COVID-19 pandemic has hit Europe and the United States the hardest, its economic impacts are reverberating in the farthest corners of the world, including in LLDCs. Clearly, the economic consequences of the pandemic will spare no country or country group. Given the high degree of heterogeneity among LLDCs, macroeconomic transmission channels and impacts of COVID-19 will, however, be significantly different across countries.

Remoteness can be a blessing but not entirely

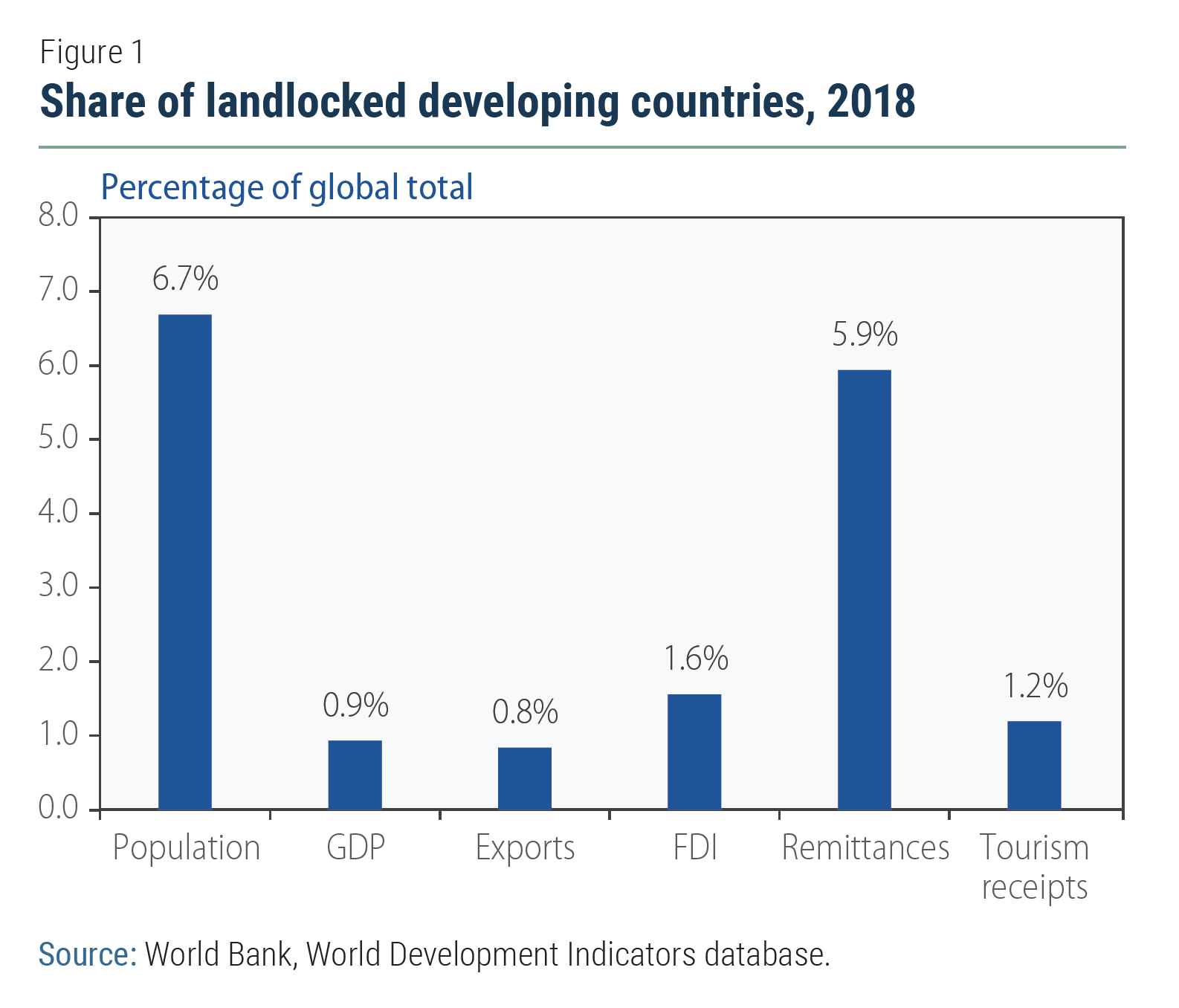

With nearly 30,000 confirmed cases—representing less than 1 per cent of all cases worldwide— LLDCs remain relatively less affected by the virus (Figure 2). Afghanistan, Armenia, Kazakhstan and the Republic of Moldova account for more than 50 per cent of all COVID-19 cases in LLDCs. These statistics, however, may well significantly understate the actual spread of infections, due to limited national capacities in testing and reporting. Most LLDCs introduced nationwide or partial lockdowns, while Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, formally introduced a state of emergency. Governments have enforced a broad range of measures, including travel bans, closures of educational institutions, cancellations of public events, remote work arrangements and social distancing. Many LLDCs—given pre-existing health conditions and limited public health capacities—remain highly vulnerable to the pandemic, particularly African LLDCs with a large share of immune-compromised population. HIV/AIDS accounted for more than a quarter of all deaths in Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho in 2017. A major COVID-19 outbreak in these countries will likely result in high death tolls. It is possible that the relative remoteness of LLDCs may offer them some degree of cushion against a large-scale outbreak. Most of these countries, barring a few LLDCs in Europe, are geographically remote from countries hardest hit by the pandemic. There are few direct flights, if any at all, between these countries and the hardest hit cities in Europe and the United States. International tourist arrivals, as percentage of host country populations, are also lower for LLDCs than other country groups, which limits the scope for foreign nationals spreading the virus. Many LLDCs are also among the most sparsely populated countries in the world. Population density is below 20 people per square kilometre in 13 LLDCs, compared to the global average of 60 people per square kilometre. Mongolia has only about 2 people living per square kilometre. Unsurprisingly, LLDCs are among the least urbanized countries in the world. The urban population, as a percentage of total population, is less than 30 per cent in LLDCs that are also LDCs, compared to the global average of 55 per cent. There are only about 10 cities with more than 1 million inhabitants in LLDCs. Economic structure may also explain the relatively few cases in LLDCs. Manufacturing activities accounts for less than 10 per of the LLDCs GDP, making them the least manufacturing-intensive economies in the world. Limited manufacturing and service sector activities mean less physical proximity and less scope for asymptomatic transmission of the virus. While physical remoteness, less concentrated economic activities, low population density and low levels of urbanization provide some protection against the spread of the virus, many LLDCs are still vulnerable—Lao PDR, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Republic of Moldova and Tajikistan, among others—as sizeable shares of their populations (up to 45 per cent in some cases) live and work abroad. As migrant workers are often compelled to live in congested, squalid quarters in the host country and as many of them have been returning to their home countries in the past couple of months, larger outbreaks in these LLDCs remain a distinct possibility.

With nearly 30,000 confirmed cases—representing less than 1 per cent of all cases worldwide— LLDCs remain relatively less affected by the virus (Figure 2). Afghanistan, Armenia, Kazakhstan and the Republic of Moldova account for more than 50 per cent of all COVID-19 cases in LLDCs. These statistics, however, may well significantly understate the actual spread of infections, due to limited national capacities in testing and reporting. Most LLDCs introduced nationwide or partial lockdowns, while Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, formally introduced a state of emergency. Governments have enforced a broad range of measures, including travel bans, closures of educational institutions, cancellations of public events, remote work arrangements and social distancing. Many LLDCs—given pre-existing health conditions and limited public health capacities—remain highly vulnerable to the pandemic, particularly African LLDCs with a large share of immune-compromised population. HIV/AIDS accounted for more than a quarter of all deaths in Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho in 2017. A major COVID-19 outbreak in these countries will likely result in high death tolls. It is possible that the relative remoteness of LLDCs may offer them some degree of cushion against a large-scale outbreak. Most of these countries, barring a few LLDCs in Europe, are geographically remote from countries hardest hit by the pandemic. There are few direct flights, if any at all, between these countries and the hardest hit cities in Europe and the United States. International tourist arrivals, as percentage of host country populations, are also lower for LLDCs than other country groups, which limits the scope for foreign nationals spreading the virus. Many LLDCs are also among the most sparsely populated countries in the world. Population density is below 20 people per square kilometre in 13 LLDCs, compared to the global average of 60 people per square kilometre. Mongolia has only about 2 people living per square kilometre. Unsurprisingly, LLDCs are among the least urbanized countries in the world. The urban population, as a percentage of total population, is less than 30 per cent in LLDCs that are also LDCs, compared to the global average of 55 per cent. There are only about 10 cities with more than 1 million inhabitants in LLDCs. Economic structure may also explain the relatively few cases in LLDCs. Manufacturing activities accounts for less than 10 per of the LLDCs GDP, making them the least manufacturing-intensive economies in the world. Limited manufacturing and service sector activities mean less physical proximity and less scope for asymptomatic transmission of the virus. While physical remoteness, less concentrated economic activities, low population density and low levels of urbanization provide some protection against the spread of the virus, many LLDCs are still vulnerable—Lao PDR, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Republic of Moldova and Tajikistan, among others—as sizeable shares of their populations (up to 45 per cent in some cases) live and work abroad. As migrant workers are often compelled to live in congested, squalid quarters in the host country and as many of them have been returning to their home countries in the past couple of months, larger outbreaks in these LLDCs remain a distinct possibility.

LLDCs face bleak economic prospects

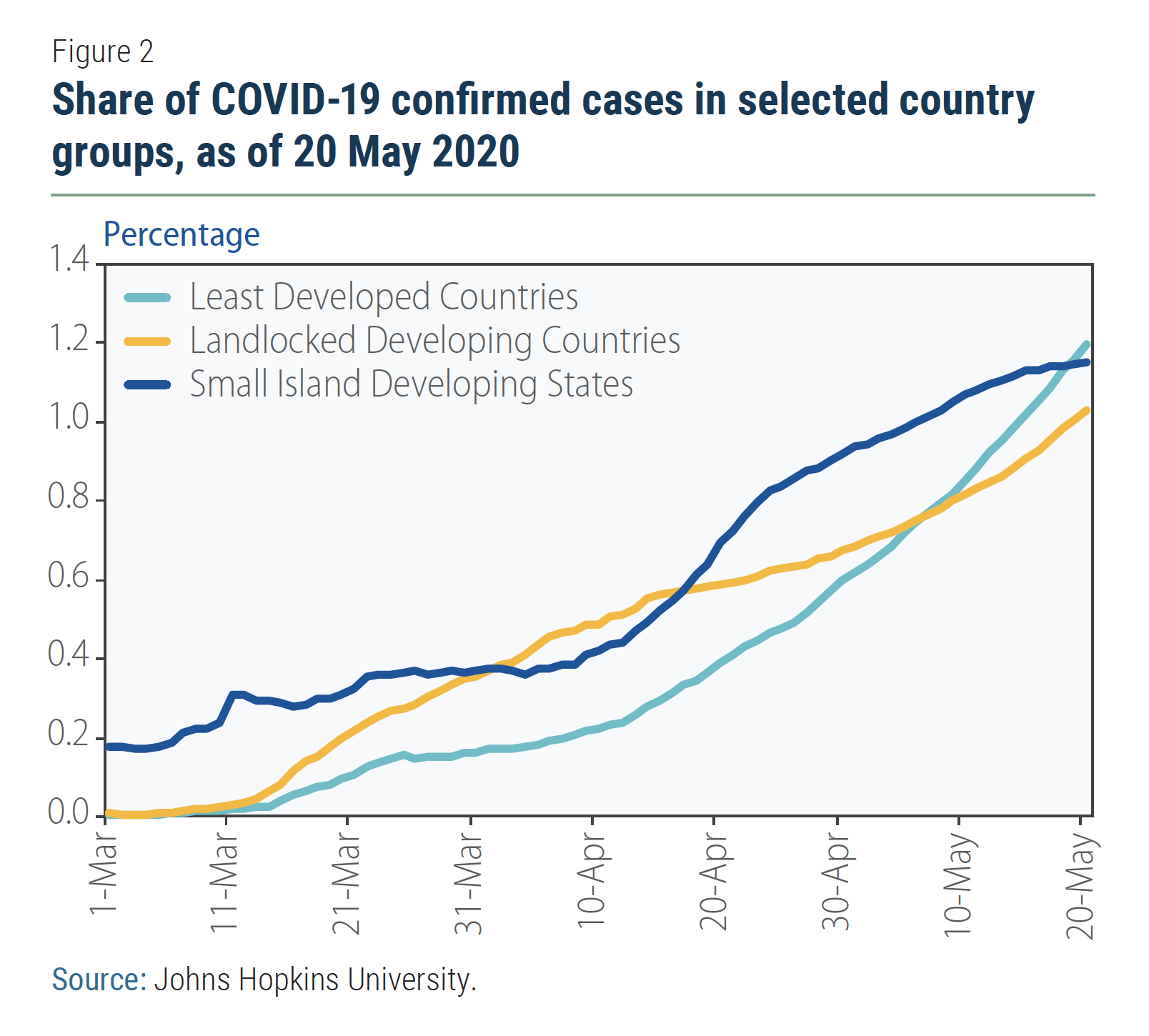

Amid an unprecedented health and economic crisis, global output is projected to decline sharply and LLDC economies will face a significant contraction in 2020. Relatively more developed ones—those that are not LDCs—will shrink by a larger magnitude relative to other LLDCs that are also LDCs (Table 1). The impact of the current crisis will be far more severe than the Great Recession in 2009, partly explained by the simultaneous collapse in demand in major economies during the first quarter of 2020. The Great Recession, which unfolded over several months, barely impacted LLDCs that are also LDCs but LLDCs that are not LDCs saw their growth rate decline by nearly 7 per cent in 2009.

Amid an unprecedented health and economic crisis, global output is projected to decline sharply and LLDC economies will face a significant contraction in 2020. Relatively more developed ones—those that are not LDCs—will shrink by a larger magnitude relative to other LLDCs that are also LDCs (Table 1). The impact of the current crisis will be far more severe than the Great Recession in 2009, partly explained by the simultaneous collapse in demand in major economies during the first quarter of 2020. The Great Recession, which unfolded over several months, barely impacted LLDCs that are also LDCs but LLDCs that are not LDCs saw their growth rate decline by nearly 7 per cent in 2009.

Collapsing commodity prices a challenge for macroeconomic stability

According to the World Economic Situation and Prospects as of mid-2020, world trade is forecast to contract by nearly 15 per cent in 2020 amid sharply reduced global demand and disruptions in global supply chains. For most LLDCs, the commodities sector remains the main driver of export and fiscal revenue and economic growth. Many of them depend on exporting one primary commodity. The energy sector in Kazakhstan, for example, accounts for around 48 per cent of GDP, over 60 per cent of exports and around 30 per cent of the budget revenue. Crude oil exports comprise 99 per cent of the exports of South Sudan (Figure 3). The oil dependent economies of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and South Sudan are already hit hard by the collapse in oil prices. In addition, the sharp slowdown in growth in China has led to a decline of around 30 per cent in the natural gas purchases from Central Asia. Large copper exporters Lao PDR, Mongolia and Zambia will experience a significant decline in export revenues and deterioration of external balance. In Latin America, Bolivia is highly dependent on exports of natural gas. The current crisis underscores the need for economic diversification away from the commodity sector in those countries, but it also undermines their ability to achieve such diversification during a crisis when they face additional constraints such as access to finance, investment and trade.

According to the World Economic Situation and Prospects as of mid-2020, world trade is forecast to contract by nearly 15 per cent in 2020 amid sharply reduced global demand and disruptions in global supply chains. For most LLDCs, the commodities sector remains the main driver of export and fiscal revenue and economic growth. Many of them depend on exporting one primary commodity. The energy sector in Kazakhstan, for example, accounts for around 48 per cent of GDP, over 60 per cent of exports and around 30 per cent of the budget revenue. Crude oil exports comprise 99 per cent of the exports of South Sudan (Figure 3). The oil dependent economies of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and South Sudan are already hit hard by the collapse in oil prices. In addition, the sharp slowdown in growth in China has led to a decline of around 30 per cent in the natural gas purchases from Central Asia. Large copper exporters Lao PDR, Mongolia and Zambia will experience a significant decline in export revenues and deterioration of external balance. In Latin America, Bolivia is highly dependent on exports of natural gas. The current crisis underscores the need for economic diversification away from the commodity sector in those countries, but it also undermines their ability to achieve such diversification during a crisis when they face additional constraints such as access to finance, investment and trade.

Remittances will likely fall sharply

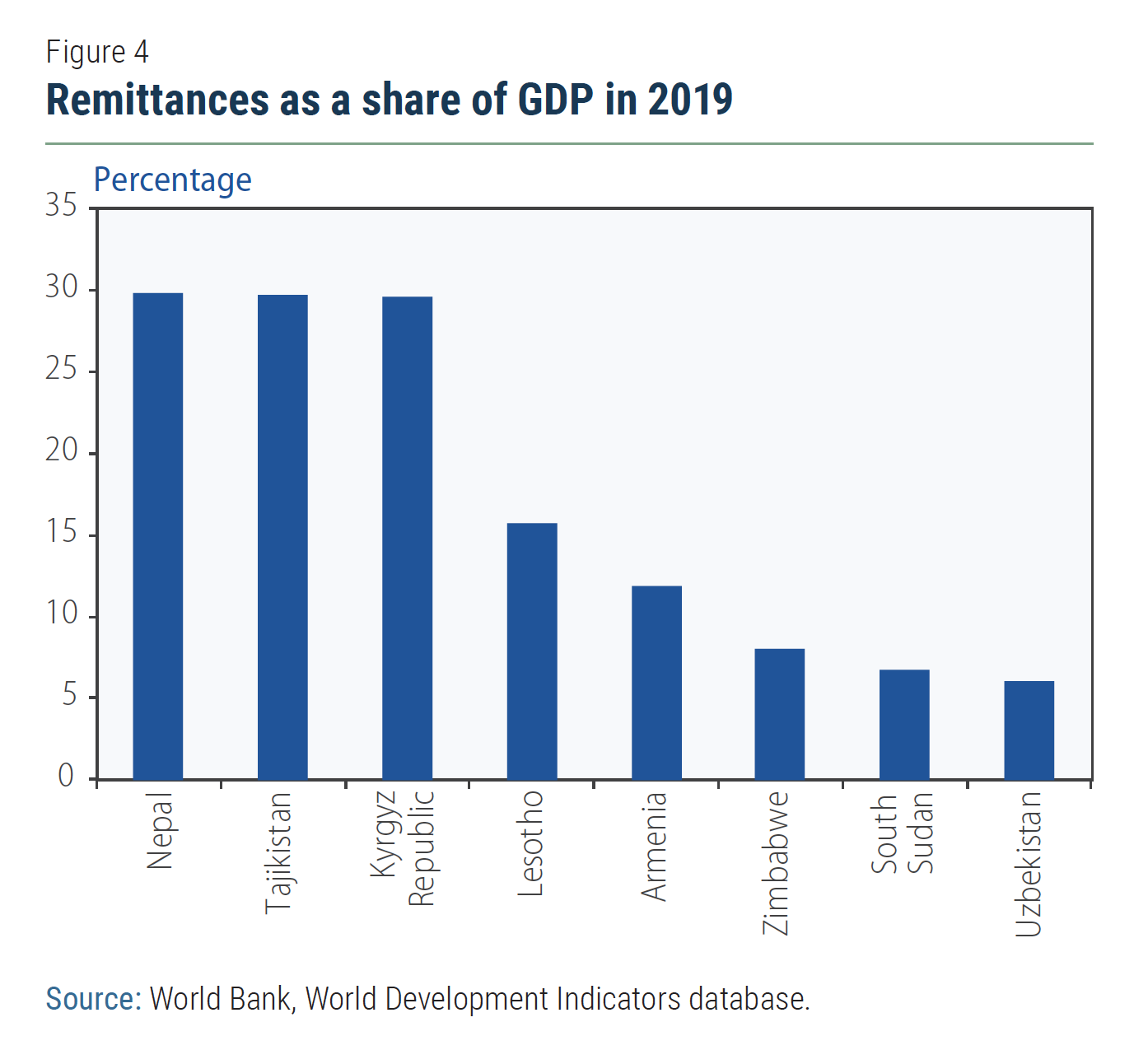

Worker remittances—representing around 30 per cent of GDP in Nepal, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan—help many LLDCs manage severe and chronic balance of payments constraints (Figure 4). For many families, it remains the sole source of income. Remittances finance private consumption and, to some extent, investment. After the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan closed their borders to foreigners, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers were unable to return to work as many of them came back to their home countries for the annual Novruz holiday. The demand for migrant workers has also decreased in the Gulf countries—a major destination for migrant workers—amid a sharp decline in economic activities. Many undocumented workers from the Lao PDR are finding it increasingly difficult to work in Thailand. A sharp contraction in remittance flows will hit many LLDC economies very hard, particularly those that rely on remittances as their main source of foreign exchange and the mainstay of their current accounts (e.g., Nepal, Tajikistan and Kyrgyz Republic). Even a 10 per cent reduction in remittance flows will translate to a significant balance of payments crisis for these LLDCs, as they have relatively low levels of international reserves. On average, international reserves held by LLDCs are enough to cover imports for about 5 months, compared to the global average of almost 10 months.

Worker remittances—representing around 30 per cent of GDP in Nepal, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan—help many LLDCs manage severe and chronic balance of payments constraints (Figure 4). For many families, it remains the sole source of income. Remittances finance private consumption and, to some extent, investment. After the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan closed their borders to foreigners, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers were unable to return to work as many of them came back to their home countries for the annual Novruz holiday. The demand for migrant workers has also decreased in the Gulf countries—a major destination for migrant workers—amid a sharp decline in economic activities. Many undocumented workers from the Lao PDR are finding it increasingly difficult to work in Thailand. A sharp contraction in remittance flows will hit many LLDC economies very hard, particularly those that rely on remittances as their main source of foreign exchange and the mainstay of their current accounts (e.g., Nepal, Tajikistan and Kyrgyz Republic). Even a 10 per cent reduction in remittance flows will translate to a significant balance of payments crisis for these LLDCs, as they have relatively low levels of international reserves. On average, international reserves held by LLDCs are enough to cover imports for about 5 months, compared to the global average of almost 10 months.

A food crisis looms large for many LLDCs

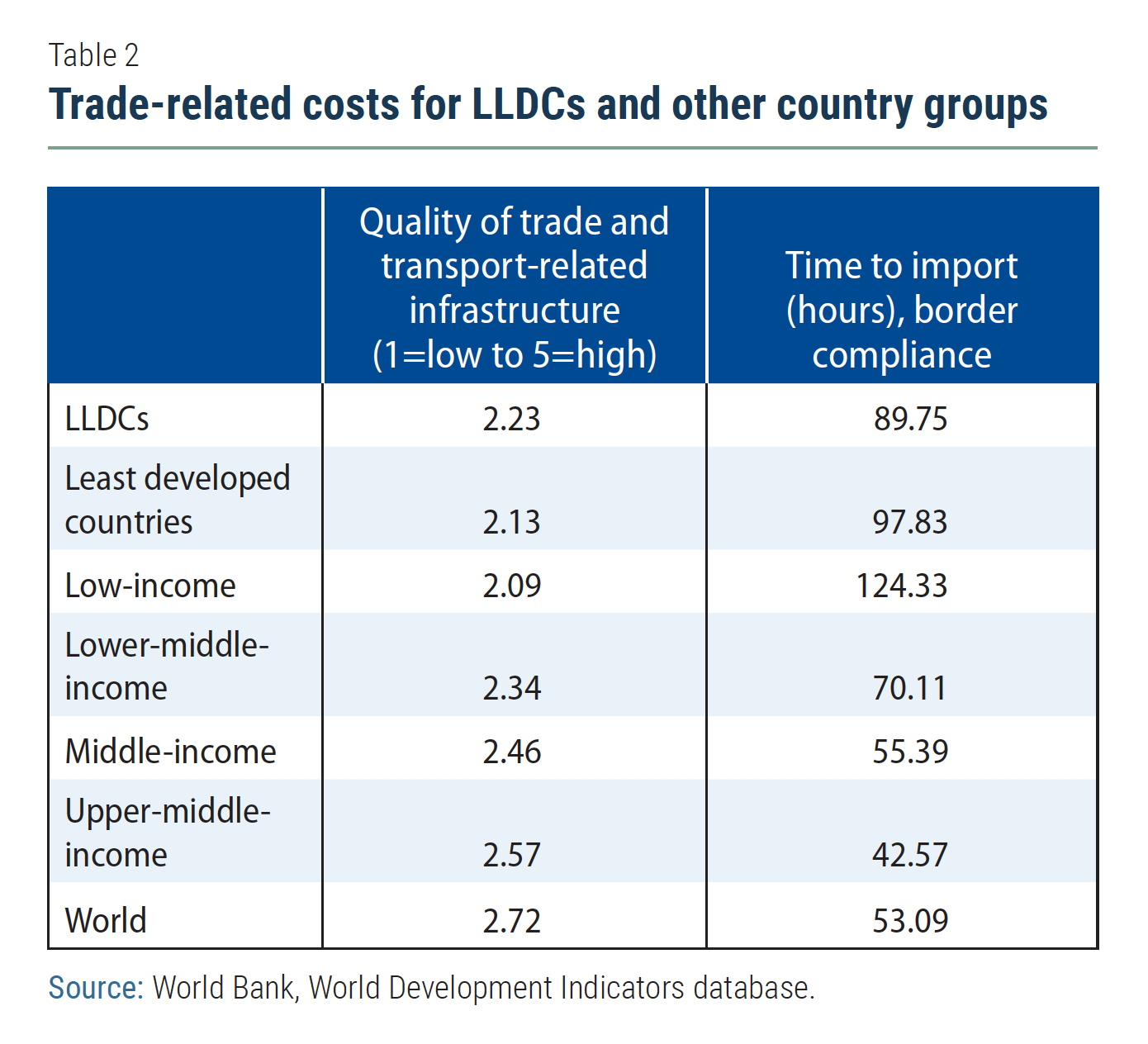

As a number of LLDCs are net food importers, the current economic crisis may soon trigger a food crisis, since many major food grain exporters around the world are introducing export restrictions to protect the domestic food supply. Kazakhstan, which accounts for around 10 per cent of global wheat exports, restricted exports of wheat, flour, potatoes and sugar in March, which will likely undermine food security in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan that heavily depend on Kazakh wheat. Kazakhstan also accounts for around 80 per cent of Afghanistan’s wheat imports. In Nepal, the slow movement of goods across the border with India and India’s decision to block exports of rice, may also lead to food shortages.  With shrinking fiscal space, many LLDCs may find it very difficult to pay for their food bill and ensure adequate food supplies, which may translate into food price inflation, potentially increasing food insecurity and triggering violence and conflict. Afghanistan is at particularly high risk, as the country faces chronic food shortages and depend on imports to meet the shortfall. LLDCs face the additional challenge of longer shipment time and higher transportation cost—relative to non-LLDCs—on imports, which will likely worsen amid disruptions in global supply chains and increase the price of food imports. They also typically have longer customs procedures and poor trade related infrastructure, which will likely constrain their ability to import food, facing an impending food crisis (Table 2).

With shrinking fiscal space, many LLDCs may find it very difficult to pay for their food bill and ensure adequate food supplies, which may translate into food price inflation, potentially increasing food insecurity and triggering violence and conflict. Afghanistan is at particularly high risk, as the country faces chronic food shortages and depend on imports to meet the shortfall. LLDCs face the additional challenge of longer shipment time and higher transportation cost—relative to non-LLDCs—on imports, which will likely worsen amid disruptions in global supply chains and increase the price of food imports. They also typically have longer customs procedures and poor trade related infrastructure, which will likely constrain their ability to import food, facing an impending food crisis (Table 2).

High levels of external debt portend a debt crisis

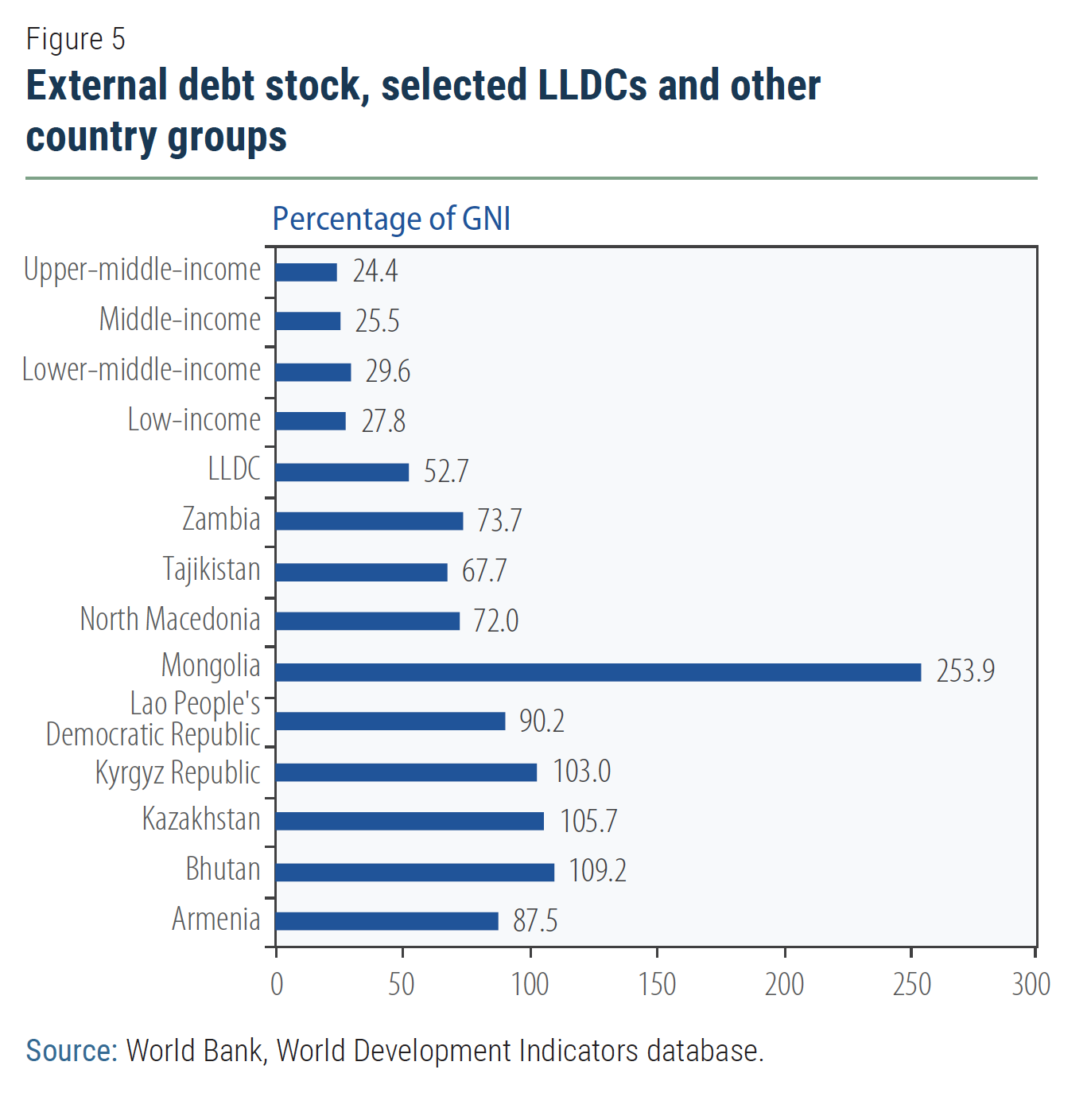

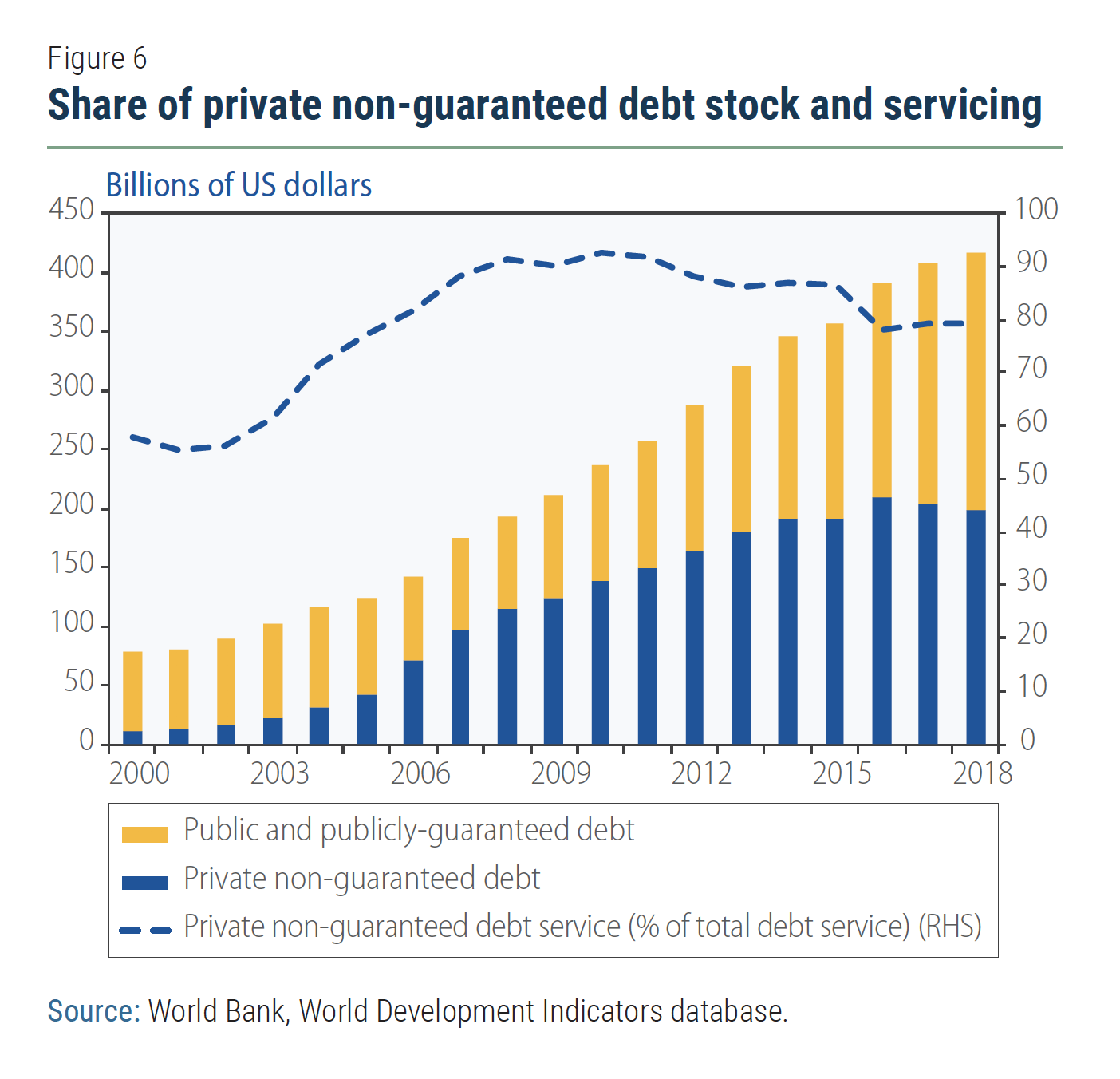

High levels of public debt are constraining the ability of many developing countries to implement the necessary fiscal responses. LLDCs include both the highest and lowest level of external debt stock relative to their gross national income (GNI). Mongolia with external debt stock at 254 per cent of GNI stands out as the country with highest level of external debt (Figure 5), while Turkmenistan with 2 per cent of debt is the country with the lowest level of external debt. Several other LLDCs have external debt stock higher than their GNI.  The key challenge for many LLDCs is that their external debt is predominantly private non-guaranteed debt which can be highly volatile. Unlike debt from bilateral and multilateral sources, debt owed to private creditors are highly pro-cyclical. Private creditors typically reduce their holding of developing country debts—and rush to safety—during the first sign of a crisis. The share of debt owed to private creditors increased from 14 per cent in 2000 to 47 per cent in 2018. The debt service on private non-guaranteed debt—owed by private entities in these countries—now accounts for nearly 80 per cent of all external debt service payments (Figure 6). Debt servicing averaged 20 per cent of the export revenue of LLDCs but exceeded 100 per cent of the export earnings of Mongolia in 2018, while it was over 50 per cent for the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, making it nearly impossible to service external debt. Given that so much of their debt is owed to private creditors, many LLDCs may find it difficult to receive moratoriums on debt servicing or meaningful debt relief. Under current market conditions, rolling over or restructuring private debt might also be very difficult, if not impossible. Therefore, substantial relief on the public and publicly guaranteed portion of their debt will remain critical for these countries to avoid a catastrophic debt default.

The key challenge for many LLDCs is that their external debt is predominantly private non-guaranteed debt which can be highly volatile. Unlike debt from bilateral and multilateral sources, debt owed to private creditors are highly pro-cyclical. Private creditors typically reduce their holding of developing country debts—and rush to safety—during the first sign of a crisis. The share of debt owed to private creditors increased from 14 per cent in 2000 to 47 per cent in 2018. The debt service on private non-guaranteed debt—owed by private entities in these countries—now accounts for nearly 80 per cent of all external debt service payments (Figure 6). Debt servicing averaged 20 per cent of the export revenue of LLDCs but exceeded 100 per cent of the export earnings of Mongolia in 2018, while it was over 50 per cent for the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, making it nearly impossible to service external debt. Given that so much of their debt is owed to private creditors, many LLDCs may find it difficult to receive moratoriums on debt servicing or meaningful debt relief. Under current market conditions, rolling over or restructuring private debt might also be very difficult, if not impossible. Therefore, substantial relief on the public and publicly guaranteed portion of their debt will remain critical for these countries to avoid a catastrophic debt default.

High inequality will likely undermine the effectiveness of fiscal measures

High inequality will likely undermine the effectiveness of fiscal measures

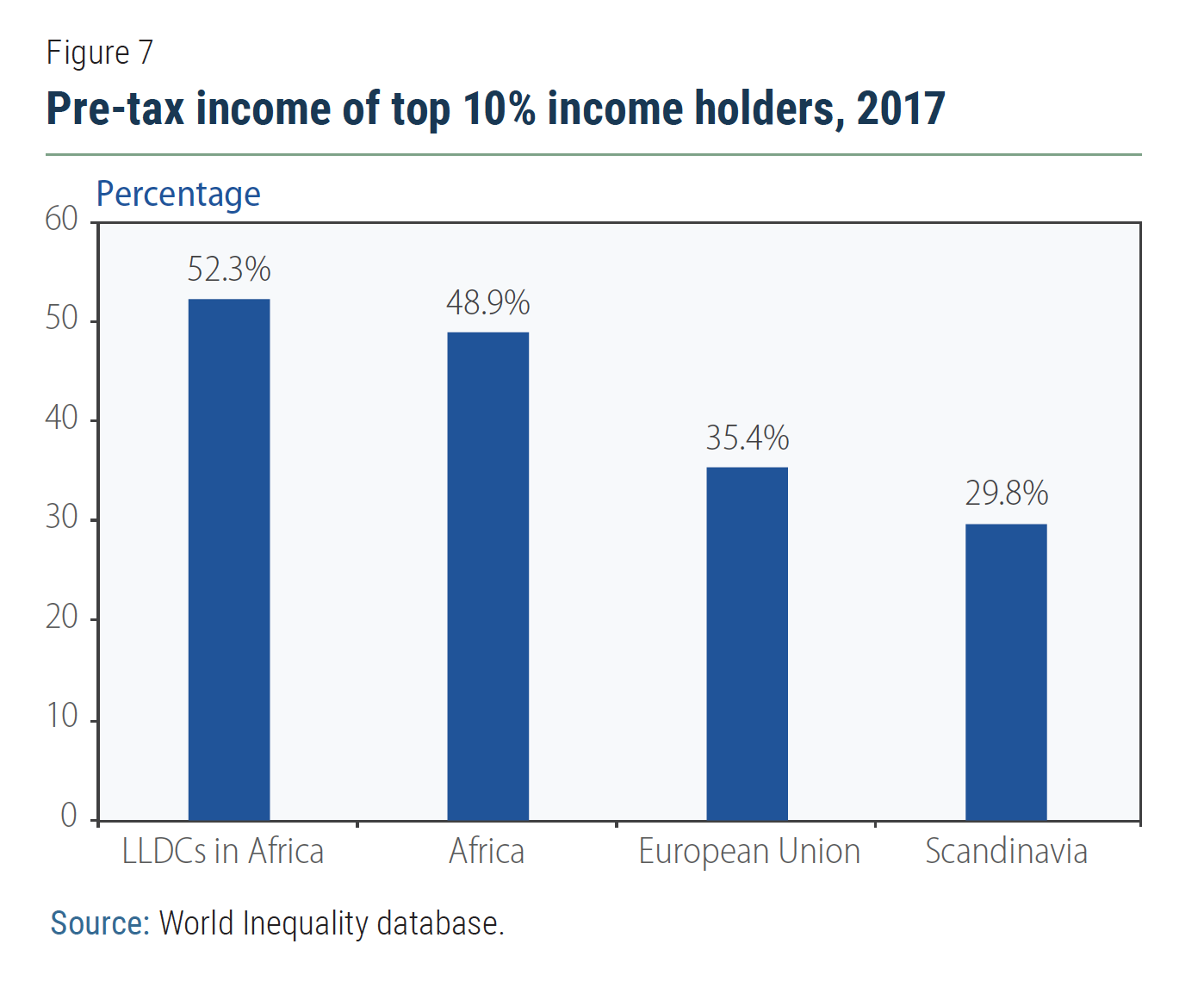

Most LLDCs are implementing expansionary fiscal measures to minimize the impact of the crisis, support businesses and households, and protect jobs. Kazakhstan, given its large sovereign wealth fund, adopted the largest stimulus package, at around $10 billion (equivalent to close to 10 per cent of GDP), to provide tax and credit relief and boost investment in public infrastructure. Niger presented a $1.7 billion (18.7 per cent of GDP) crisis response plan to donors, divided into an immediate health response and broader economic and social mitigation. However, stimulus measures supporting the supply-side will unlikely boost household and business spending amid lockdowns and continued uncertainties. Moreover, the efficiency of those measures may be constrained by the high degree of inequality in many LLDCs. With their high dependence on commodities and narrow manufacturing base, and small number of relatively well-paying manufacturing and service sector jobs, LLDCs have one of the highest levels of income inequality in the world. Broad-based, inclusive growth remained elusive for many LLDCs, triggering instability and conflict. The top 10 per cent of income holders receive more than 52 per cent of pre-tax income in African LLDCs, for which data is available (Figure 7). The relatively high share of income of the top 10 per cent likely indicate skewed and concentrated political power in these countries, suggesting that fiscal and monetary measures may not necessarily prioritize the interest of the poorest and the most vulnerable segments in these countries.  High levels of income and wealth inequality—which usually allow economic elites to exert disproportionate influence on economic decision-making and undermines transparency and accountability—will likely constrain the ability of these countries to implement effective stimulus measures that will help the most vulnerable segments of their population. Undue economic influence of the wealthy and powerful, the lack of transparency and accountability, and potential corruption will likely undermine the efficacy of fiscal measures, exacerbate the crisis and further widen income inequality in many LLDCs. It is also unlikely that fiscal support will reach the large informal sector in many LLDCs.

High levels of income and wealth inequality—which usually allow economic elites to exert disproportionate influence on economic decision-making and undermines transparency and accountability—will likely constrain the ability of these countries to implement effective stimulus measures that will help the most vulnerable segments of their population. Undue economic influence of the wealthy and powerful, the lack of transparency and accountability, and potential corruption will likely undermine the efficacy of fiscal measures, exacerbate the crisis and further widen income inequality in many LLDCs. It is also unlikely that fiscal support will reach the large informal sector in many LLDCs.

Emergency relief is helping LLDCs avoid an immediate crisis but more is needed

Many LLDCs, especially in Africa and South Asia, depend on official development assistance (ODA) flows to finance their fiscal deficits, which will likely shrink significantly in 2020. Afghanistan possibly faces the most severe challenge as ODA covers 50 per cent of fiscal spending. The sharp economic downturn, falling export revenue and import duties will exacerbate the shortfall at a time when the economy desperately needs to implement stimulus measures to prevent a total meltdown. A contraction in government spending in Afghanistan, Central African Republic or South Sudan, among others, may exacerbate violence and political instability and potentially reverse years of development gains. As trade revenue and remittances began to fall, global private credit markets tightened and capital outflows surged, the central banks of many LLDCs intervened to stem exchange rate volatility. Amid tightening credit conditions and rising balance of payments pressures, many LLDCs have turned to multilateral lenders to secure financial relief, minimize the fallout of economic collapse and avoid a balance of payments crisis. The IMF has approved immediate debt service relief to 25 member countries to help address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The LLDCs in Africa and Asia—Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Malawi, Mali, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda and Tajikistan—account for 40 per cent of the IMF debt relief. The IMF Executive Board has also approved requests for emergency assistance for Afghanistan ($220 million), Ethiopia ($411 million), Kyrgyzstan ($120 million) and Tajikistan ($189 million) and it is considering other countries’ requests. The World Bank’s dedicated COVID-19 Fast-Track Facility is extending credit to a number of LLDCs, namely, Afghanistan, Burundi, Bhutan, Central African Republic, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Kyrgyzstan, Lao PDR, Mali, Malawi, Mongolia, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, as well as providing other forms of finance and redeploying existing projects. While these emergency lines of credit are helping LLDCs to avoid an immediate crisis, they will remain inadequate to address the longer-term economic impact of the pandemic. There is a clear need for a comprehensive economic rescue plan—not just emergency credit—to prevent the possible collapse of the LLDC economies, which will not only stifle growth but also likely trigger widespread unrest, violence and conflicts as many of these countries are conflict hotspots. The United Nations need to strengthen its early warnings and forward guidance to the international community to develop a timely rescue and recovery plan to safeguard and accelerate sustainable development in LLDCs before it is too late. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development should guide international efforts to support LLDCs. The cost of inaction or delayed action will be too high, as economic crisis, joblessness and hunger in LLDCs will inevitably fuel conflicts that will affect not only them but also their neighbours and the wider world beyond their immediate borders.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations