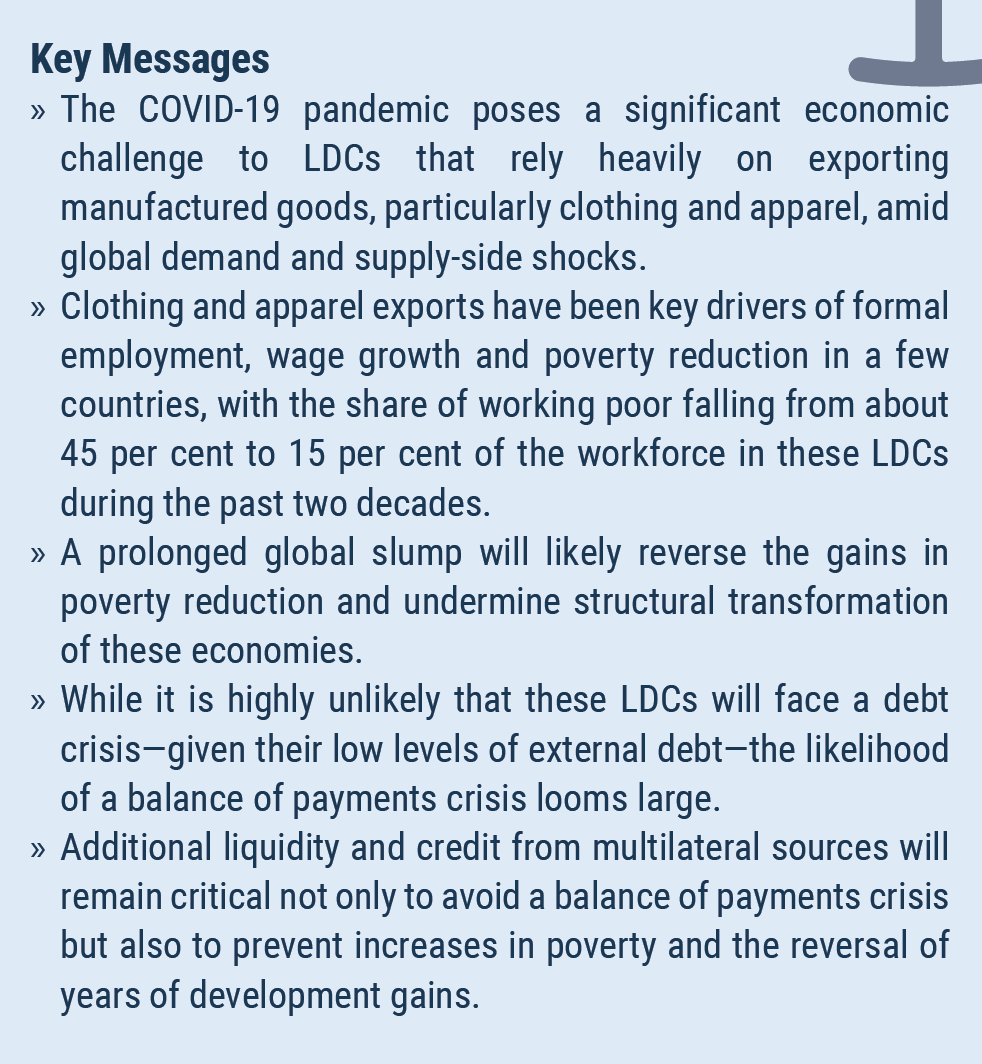

The COVID-19 pandemic is yet to directly hit the least developed countries (LDCs), although most are already experiencing severe economic pain amid shutdowns, falling commodity prices and declining exports. LDCs are, on average, highly dependent on commodities. Oil, minerals, food and other commodities account for more than 70 per cent of their merchandise exports. High dependence on commodities exports make most LDCs extremely vulnerable to global shocks, and many are bracing for a severe economic downturn this year. However, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will be equally devastating for LDCs that do not rely on commodities as a main source of foreign exchange. Only six LDCs—Bangladesh, Cambodia, Haiti, the Gambia, Nepal and Lesotho—receive more than 50 per cent of their export revenue from exporting manufactured goods (Figure 1). Manufacturing accounts for more than 95 per cent of Bangladesh’s exports, compared to an average of less than 30 per cent for all LDCs, and 75 per cent for the Asian tiger economies. These six non-commodity dependent LDCs, however, largely rely on low-end and mostly labour intensive manufacturing exports, compared to higher value added and skill-intensive exports from the Asian tiger economies. These six LDCs present a development pathway for other LDCs to pursue transformation of their economies and foster development. Manufacturing exports enable a least developed country to connect with the global supply-chain, importing technology and intermediate inputs and exporting finished products. This enables gradual accumulation of productive capacities and productivity growth—the key enabler of economic transformation. A number of African LDCs—Ethiopia, Senegal and Rwanda—are at the cusp of this transformation with their manufacturing exports taking off in recent years.

The COVID-19 pandemic is yet to directly hit the least developed countries (LDCs), although most are already experiencing severe economic pain amid shutdowns, falling commodity prices and declining exports. LDCs are, on average, highly dependent on commodities. Oil, minerals, food and other commodities account for more than 70 per cent of their merchandise exports. High dependence on commodities exports make most LDCs extremely vulnerable to global shocks, and many are bracing for a severe economic downturn this year. However, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will be equally devastating for LDCs that do not rely on commodities as a main source of foreign exchange. Only six LDCs—Bangladesh, Cambodia, Haiti, the Gambia, Nepal and Lesotho—receive more than 50 per cent of their export revenue from exporting manufactured goods (Figure 1). Manufacturing accounts for more than 95 per cent of Bangladesh’s exports, compared to an average of less than 30 per cent for all LDCs, and 75 per cent for the Asian tiger economies. These six non-commodity dependent LDCs, however, largely rely on low-end and mostly labour intensive manufacturing exports, compared to higher value added and skill-intensive exports from the Asian tiger economies. These six LDCs present a development pathway for other LDCs to pursue transformation of their economies and foster development. Manufacturing exports enable a least developed country to connect with the global supply-chain, importing technology and intermediate inputs and exporting finished products. This enables gradual accumulation of productive capacities and productivity growth—the key enabler of economic transformation. A number of African LDCs—Ethiopia, Senegal and Rwanda—are at the cusp of this transformation with their manufacturing exports taking off in recent years.  The COVID-19 pandemic presents a high risk to the nascent manufacturing sectors of these LDCs. Their structural transformation will suffer a serious setback if global demand for manufacturing exports from LDCs contract sharply this year and remain depressed in the near term.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a high risk to the nascent manufacturing sectors of these LDCs. Their structural transformation will suffer a serious setback if global demand for manufacturing exports from LDCs contract sharply this year and remain depressed in the near term.

Spread of the pandemic

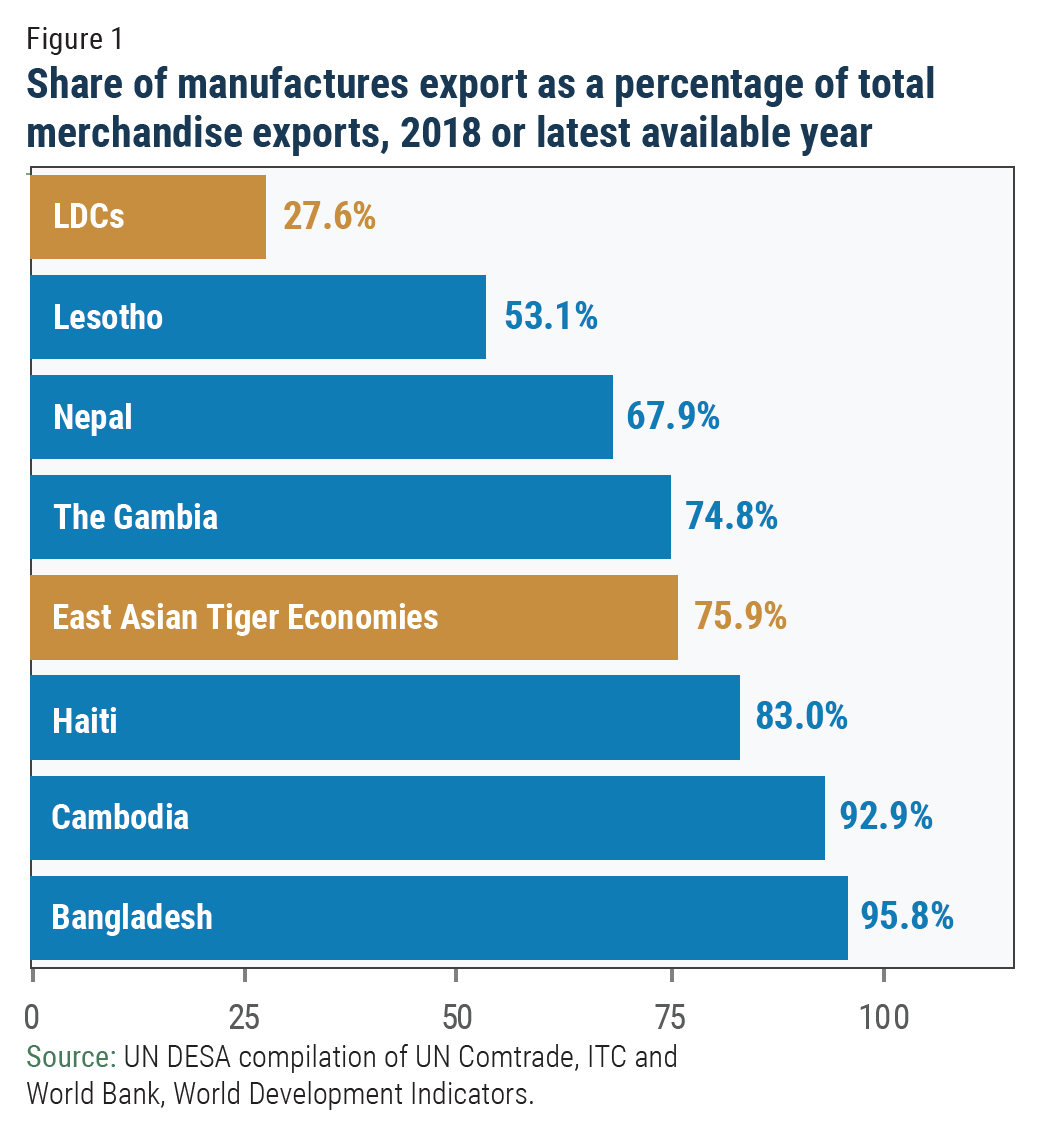

The number of confirmed cases and COVID-19 related deaths is still low in most LDCs. Total deaths in LDCs account for 0.2 per cent of the global total (Figure 2). Bangladesh has had the highest number of confirmed cases while, on the other end of the spectrum, Lesotho is yet to report a single confirmed case of the disease. Low numbers of confirmed cases or mortality in LDCs, however, offer no reason for celebration. Amid extremely low levels of testing, the spread of the pandemic is most likely under-reported. There is significant anxiety and caution that the pandemic may flare up anytime and wreak havoc on a short notice, especially worrying given the limited capacity of health care systems in these countries.  All six of these manufacturing-dependent LDCs have implemented a range of preventive measures, including cancelling public events and elections, closing or limiting public services, commercial activities, and social gatherings, mandating social distancing measures, and implementing curfews. In Bangladesh, for example, authorities imposed a lockdown on hotspots in Dhaka where cases have been identified. Most countries have also implemented stricter controls on foreign travel. A few have cancelled all non-essential international flights and most require foreigners to self-quarantine to obtain a health certificate and have sufficient travel insurance. In Cambodia, migrant workers returning from Thailand are required to remain in quarantine for two weeks.

All six of these manufacturing-dependent LDCs have implemented a range of preventive measures, including cancelling public events and elections, closing or limiting public services, commercial activities, and social gatherings, mandating social distancing measures, and implementing curfews. In Bangladesh, for example, authorities imposed a lockdown on hotspots in Dhaka where cases have been identified. Most countries have also implemented stricter controls on foreign travel. A few have cancelled all non-essential international flights and most require foreigners to self-quarantine to obtain a health certificate and have sufficient travel insurance. In Cambodia, migrant workers returning from Thailand are required to remain in quarantine for two weeks.

Risks of a narrow export basket

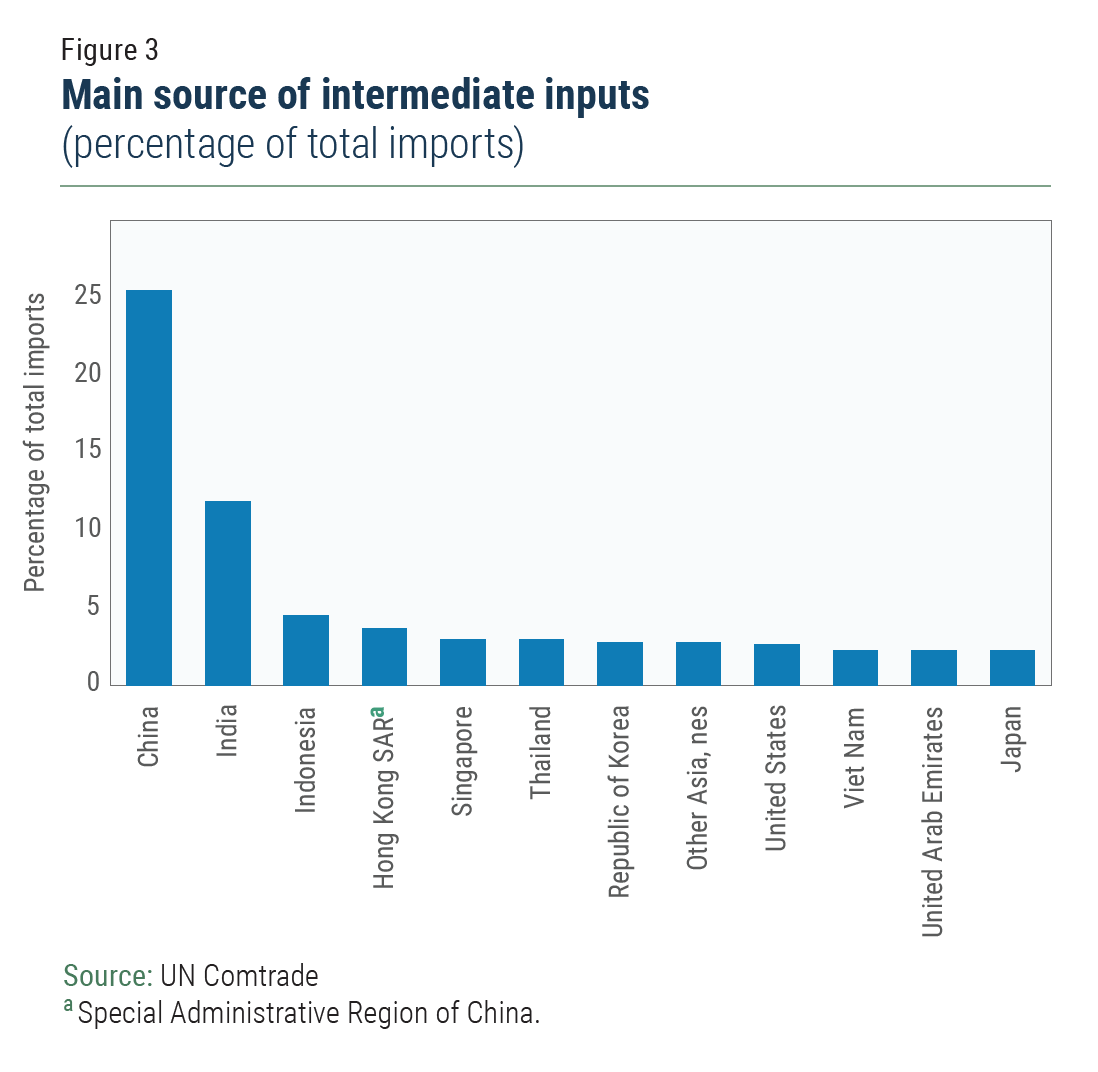

A single type of product—clothing and apparel—account for more than 50 per cent of exports of these six LDCs, which makes them very susceptible to external demand shocks. For Bangladesh, Cambodia, Haiti and Lesotho, the share is over 85 per cent. Household spending on clothing and apparel is discretionary and therefore highly income elastic. Facing an income shock, households can forego buying clothes. A 1.3 per cent decline in US GDP growth during the Global Financial Crisis in 2009 resulted in more than 12 per cent decline in imports of clothing and apparel from the rest of the world. Furthermore, demand for non-essentials like clothing does not necessarily pick up immediately after the crisis. Thus, a postponed consumption is usually a foregone consumption.  Unlike in relatively more advanced manufacturing economies, these LDCs lack sufficiently large domestic demand to absorb excess supply as external demand falls. This means production of a sizeable share of exportable products comes to a standstill when external demand contracts sharply, leading to mass layoffs of workers employed in the sector. LDC manufacturing is also more vulnerable to external conditions, as 30 per cent of their exports require intermediate inputs imported from abroad. They also rely on a few large economies to procure intermediate inputs (Figure 3). Disruption in global production and supply chains means that many of these LDCs may not be able to procure raw materials and intermediate inputs to continue with production, even if there is demand for their products.

Unlike in relatively more advanced manufacturing economies, these LDCs lack sufficiently large domestic demand to absorb excess supply as external demand falls. This means production of a sizeable share of exportable products comes to a standstill when external demand contracts sharply, leading to mass layoffs of workers employed in the sector. LDC manufacturing is also more vulnerable to external conditions, as 30 per cent of their exports require intermediate inputs imported from abroad. They also rely on a few large economies to procure intermediate inputs (Figure 3). Disruption in global production and supply chains means that many of these LDCs may not be able to procure raw materials and intermediate inputs to continue with production, even if there is demand for their products.

A sharp contraction on the horizon

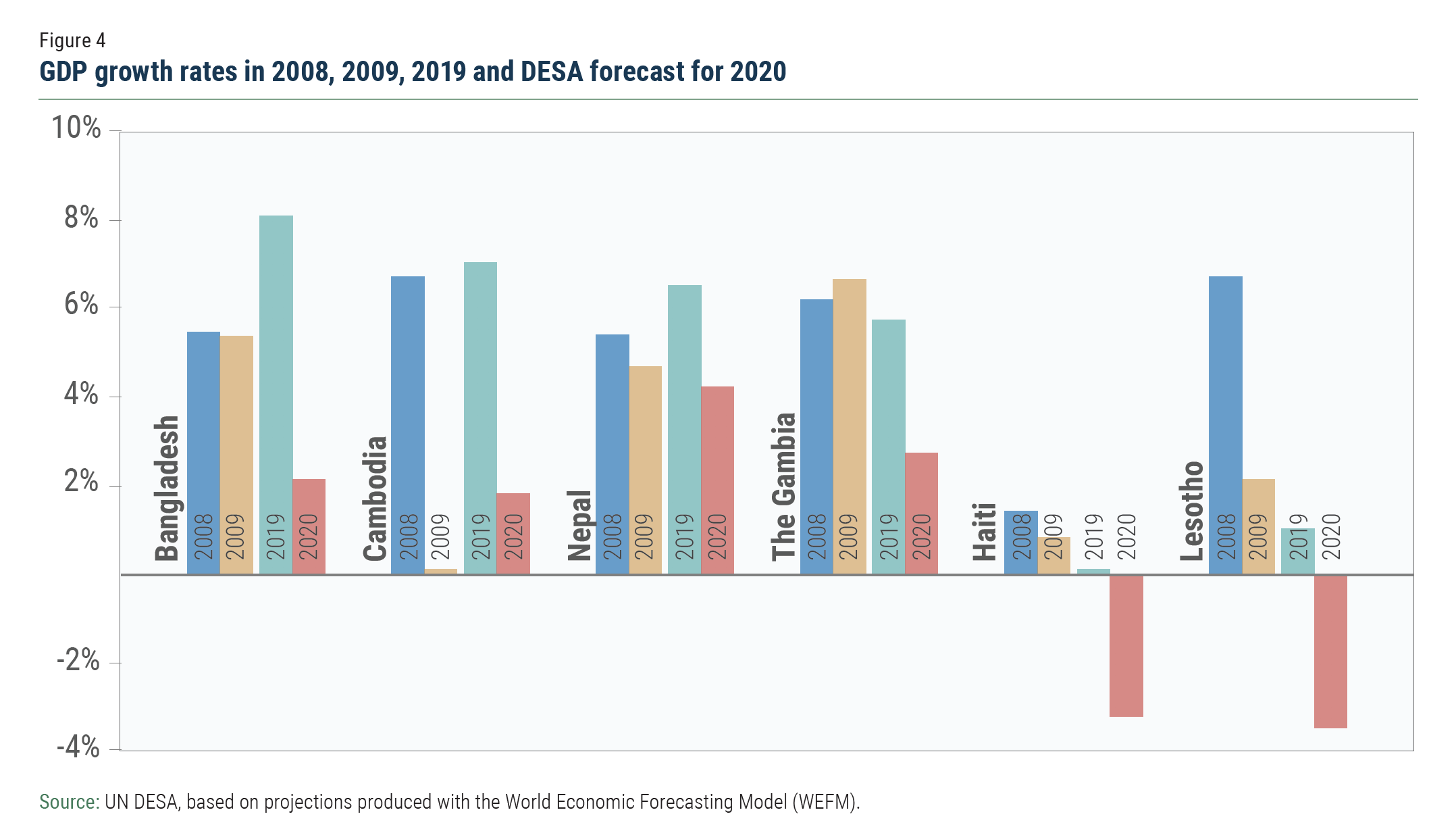

More than 80 per cent of apparel exports from these LDCs go to Europe and North America. As the current crisis will sharply contract employment and income in Europe and the United States, demand for apparel and clothing will also experience a sharp decline. Given the magnitude of the crisis, clothing exports from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Lesotho and Haiti could fall by at least 20 per cent. The direct and spillover effects of the sharp fall in exports could translate to at least 2-3 per cent decline in GDP growth in 2020. Their vulnerability is further compounded by the fact that these economies are also highly dependent on remittances, which are likely to experience a similar level of contraction this year. According to UN DESA forecasts, GDP growth of these LDCs will decline, on average, by 4 percentage points relative to their growth rates in 2019. During the global financial crisis, GDP growth of these economies fell by only 2 per cent. Given weak economic conditions even before the COVID-19 outbreak, Haiti and Lesotho are expected to register negative GDP growth in 2020 (Figure 4).

Poverty will increase, sharply

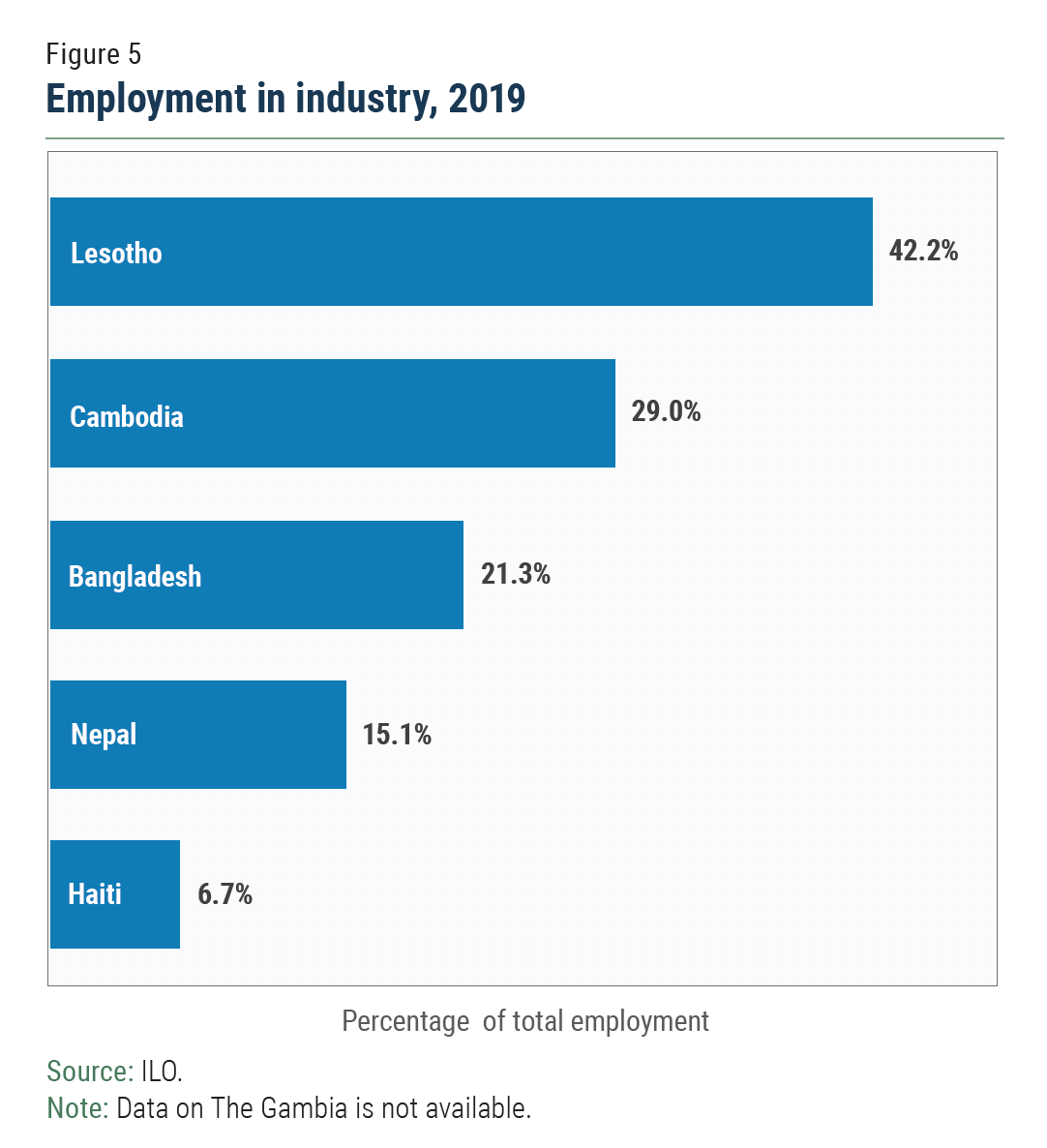

Manufacturing led export growth allowed rapid expansion of formal employment in these economies. The number of people—mostly women—working in the clothing sector in Bangladesh increased from 200,000 in 1990s to over 4,000,000 by 2018, contributing to a significant decline in poverty. Manufacturing sector’s share of total employment in Cambodia increased from 7 per cent in 2000 to 29 per cent in 2019. Manufacturing accounted for over 40 per cent of all employment in Lesotho (Figure 5).  The rise of employment in manufacturing sector, along with rising real wages, led to significant reduction in the number of working poor in Cambodia. The share of the workforce earning less than $1.90/day declined from more than 70 per cent in 2000 to under 10 per cent in 2020 (Figure 6). A sharp fall in global demand for clothing, and the consequent hit on manufacturing sectors, will lead to a large increase in unemployment in the formal sector of these economies. Rising unemployment will dampen, and possibly reverse, wage growth, destroy millions of decent jobs and derail the achievement of SDG-8 (Decent work and economic growth). Any decline in external demand will disproportionately hurt poor households employed in labor intensive manufacturing and undermine their efforts to eradicate extreme poverty and achieve SDG-1.

The rise of employment in manufacturing sector, along with rising real wages, led to significant reduction in the number of working poor in Cambodia. The share of the workforce earning less than $1.90/day declined from more than 70 per cent in 2000 to under 10 per cent in 2020 (Figure 6). A sharp fall in global demand for clothing, and the consequent hit on manufacturing sectors, will lead to a large increase in unemployment in the formal sector of these economies. Rising unemployment will dampen, and possibly reverse, wage growth, destroy millions of decent jobs and derail the achievement of SDG-8 (Decent work and economic growth). Any decline in external demand will disproportionately hurt poor households employed in labor intensive manufacturing and undermine their efforts to eradicate extreme poverty and achieve SDG-1.

Trade shock may trigger a balance of payments crisis

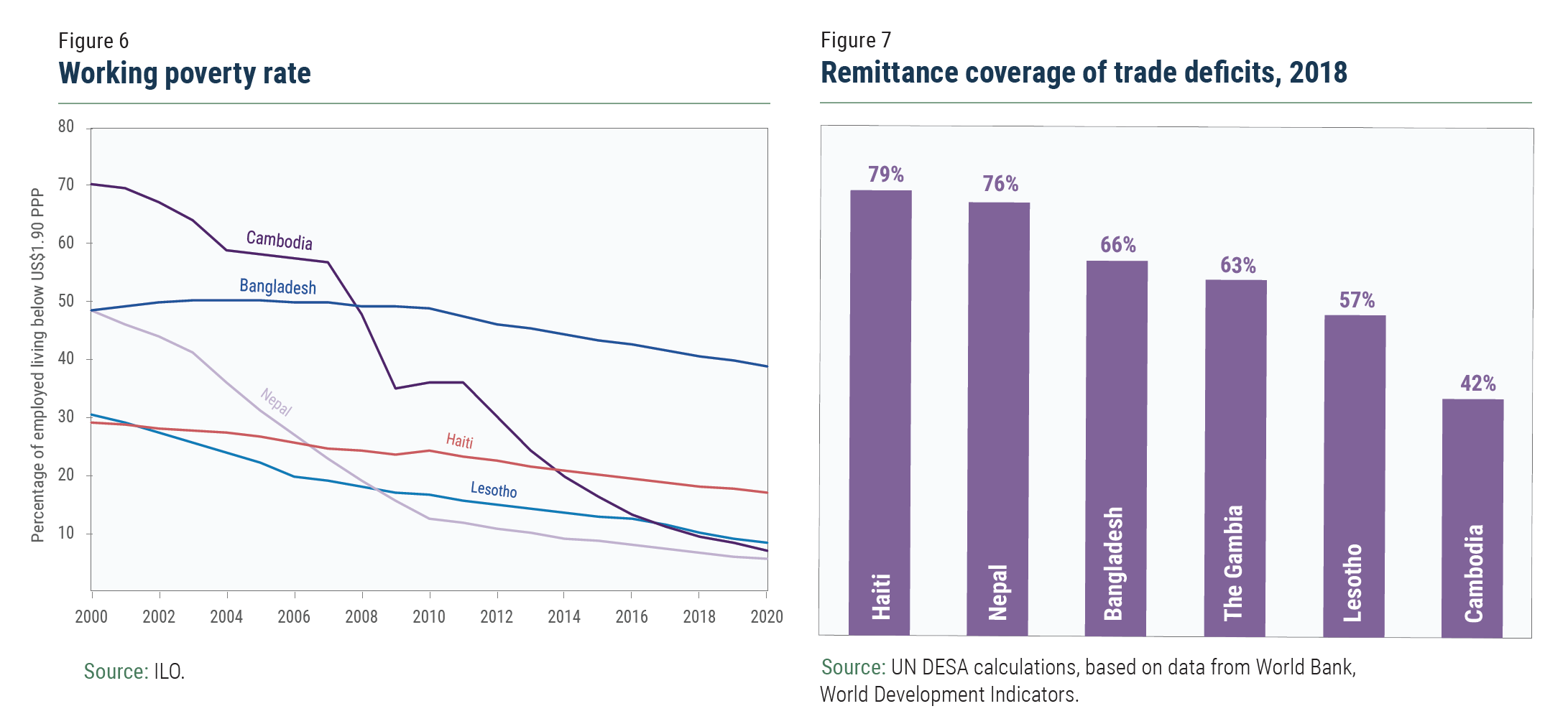

The projected 4.0 decline in GDP growth suggests the impact of this shock will be significantly more devastating for these LDCs relative to the shock they experienced in 2009. As these LDCs are also net food and oil importers, and as food and oil imports tend to be inelastic, their import bills will remain high relative to export earnings, digging a larger hole in their current account deficits. Lower oil prices will give them some relief but it will not be sufficient to offset the decline in export revenue.  These economies also rely heavily on remittances, which is a critical complementary source of external flows. Remittances account for more than 30 per cent of GDP of Haiti, Nepal and Lesotho. The COVID-19 crisis is likely to severely shrink remittance inflows as many migrant workers are likely to lose jobs and return to their home countries. More importantly, remittances cover between 40–80 per cent of their trade deficits, which in these countries range from 8 per cent to 40 per cent of GDP (Figure 7). Without remittances, their current account deficits are unsustainable, even more so in the current context of rapidly falling manufacturing export revenues. Given that these economies have relatively low levels of external and public debt, they are unlikely to face debt distress in the near term. But the dollarized economy of Cambodia and the South African rand-based economy of Lesotho will face additional challenges. In case of an appreciation of US dollar vis-à-vis euro, for example, Cambodian products will become more expensive in the European market, hurting their exports and further weakening their balance of payments.

These economies also rely heavily on remittances, which is a critical complementary source of external flows. Remittances account for more than 30 per cent of GDP of Haiti, Nepal and Lesotho. The COVID-19 crisis is likely to severely shrink remittance inflows as many migrant workers are likely to lose jobs and return to their home countries. More importantly, remittances cover between 40–80 per cent of their trade deficits, which in these countries range from 8 per cent to 40 per cent of GDP (Figure 7). Without remittances, their current account deficits are unsustainable, even more so in the current context of rapidly falling manufacturing export revenues. Given that these economies have relatively low levels of external and public debt, they are unlikely to face debt distress in the near term. But the dollarized economy of Cambodia and the South African rand-based economy of Lesotho will face additional challenges. In case of an appreciation of US dollar vis-à-vis euro, for example, Cambodian products will become more expensive in the European market, hurting their exports and further weakening their balance of payments.

Limited domestic fiscal space, multilateral support critical

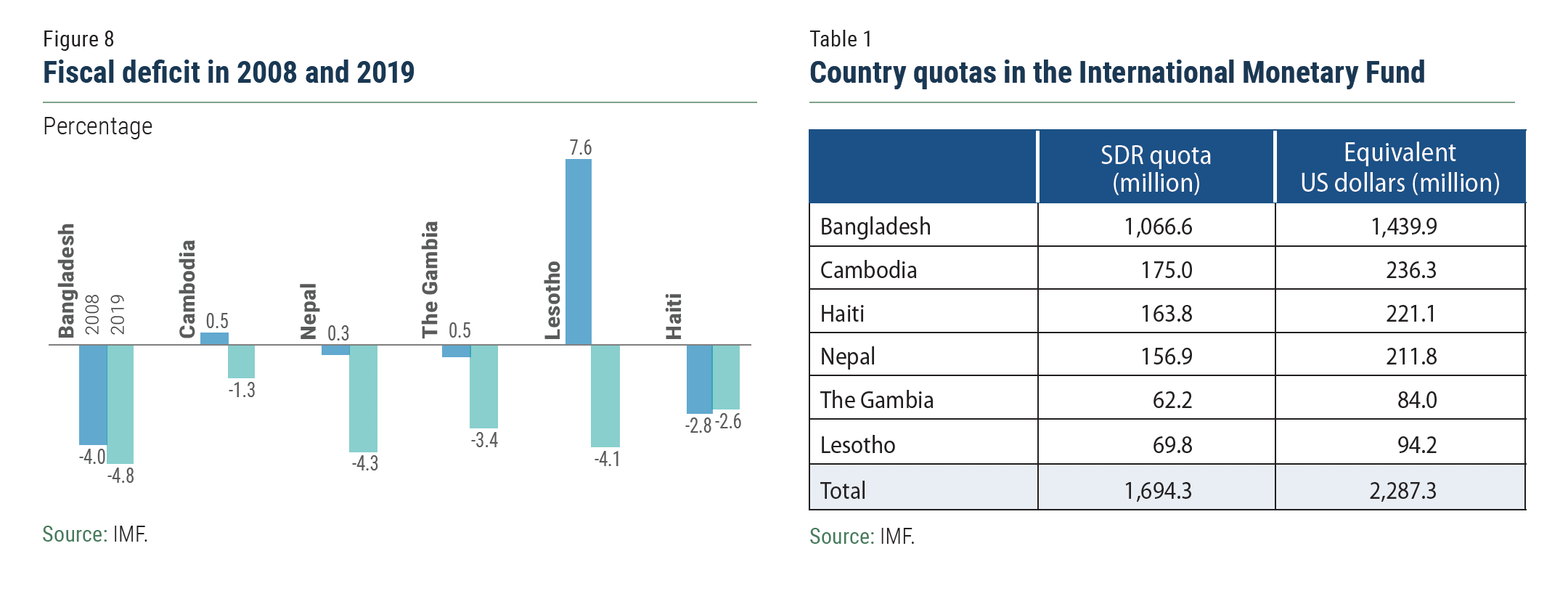

These manufacturing-dependent LDCs—Bangladesh, Cambodia, Haiti, the Gambia, Nepal and Lesotho—are aggressively easing monetary conditions to ensure adequate liquidity in the financial sector through multiple mechanisms: reducing refinancing and reference rates, lowering reserve requirements, implementing extended lending facilities, buying treasury bonds and bills from banks and easing loan repayment obligations. However, given the nature of the shock, fiscal policies are expected to play a more relevant role in containing the health and economic impacts of the pandemic. These LDCs, however, have a significantly a higher level of fiscal deficit today than they had in 2008, which makes it harder for them to implement large fiscal stimulus packages (Figure 8). Despite significant fiscal constraints, governments are implementing a wide range of support measures, including rolling out preparedness and response plans, increasing health spending, providing cash transfers, and expanding social assistance for vulnerable groups and emergency funds for sectors most affected by the crisis.  Importantly, it is unlikely that these LDCs can significantly expand their fiscal packages with domestic resources alone. It will be very difficult for governments to borrow from the domestic banking sectors or the capital market without crowding out private borrowing, potentially constraining private investment. Monetization of debt will increase the risk of inflation, which may be costly during an economic downturn. They also generally lack access to the international capital market. Clearly, there is a need for a large-scale, coordinated and comprehensive multilateral response that can help these LDCs confront this unprecedented health and economic crisis. Given their relatively low level of external debt, averaging about 35 per cent of GDP, most of these economies should be able to borrow from multilateral creditors. These economies may immediately access financing from the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) and the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Low income countries facing exogenous shocks, natural disasters, and emergencies resulting from fragility can borrow from RCF, which has made about $10 billion of emergency funds available for low income countries, and about $40 billion for emerging economies. Financing from RCF carries no ex post conditionality and is available at zero interest rate with grace period of 5½ years, and a final maturity of 10 years. Financing from RFI is also available for urgent balance of payments needs of the Member States. Given the severity of the current crisis, IMF has temporarily increased the RCF and RFI borrowing limits from 50 to 100 percent of quota per year, and from 100 to 150 percent of quota on a cumulative basis, with the higher limits available for an initial six-month period, from 6 April to 5 October 2020 (see Table 1 for each country's SDR quota). These LDCs can also borrow up to 145 percent of their quota from Stand-By Arrangements (SBA)—repayable in 3¼ to 5 years—to avoid a balance of payments crisis. It will remain critical that these countries—home to more than 25 million people living in extreme poverty—are able to access necessary financial resources from multilateral institutions to ramp up their health responses, expand their fiscal stimulus packages and accelerate investments in sustainable development. Robust and timely international support will enable these LDCs protect decent jobs and prevent the rise of poverty.

Importantly, it is unlikely that these LDCs can significantly expand their fiscal packages with domestic resources alone. It will be very difficult for governments to borrow from the domestic banking sectors or the capital market without crowding out private borrowing, potentially constraining private investment. Monetization of debt will increase the risk of inflation, which may be costly during an economic downturn. They also generally lack access to the international capital market. Clearly, there is a need for a large-scale, coordinated and comprehensive multilateral response that can help these LDCs confront this unprecedented health and economic crisis. Given their relatively low level of external debt, averaging about 35 per cent of GDP, most of these economies should be able to borrow from multilateral creditors. These economies may immediately access financing from the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) and the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Low income countries facing exogenous shocks, natural disasters, and emergencies resulting from fragility can borrow from RCF, which has made about $10 billion of emergency funds available for low income countries, and about $40 billion for emerging economies. Financing from RCF carries no ex post conditionality and is available at zero interest rate with grace period of 5½ years, and a final maturity of 10 years. Financing from RFI is also available for urgent balance of payments needs of the Member States. Given the severity of the current crisis, IMF has temporarily increased the RCF and RFI borrowing limits from 50 to 100 percent of quota per year, and from 100 to 150 percent of quota on a cumulative basis, with the higher limits available for an initial six-month period, from 6 April to 5 October 2020 (see Table 1 for each country's SDR quota). These LDCs can also borrow up to 145 percent of their quota from Stand-By Arrangements (SBA)—repayable in 3¼ to 5 years—to avoid a balance of payments crisis. It will remain critical that these countries—home to more than 25 million people living in extreme poverty—are able to access necessary financial resources from multilateral institutions to ramp up their health responses, expand their fiscal stimulus packages and accelerate investments in sustainable development. Robust and timely international support will enable these LDCs protect decent jobs and prevent the rise of poverty.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations