The COVID-19 pandemic puts Small island developing economies in dire straits

The COVID-19 pandemic puts Small island developing economies in dire straits

Small island developing countries—accounting for less than 1% of the world’s population—represent nearly 20% of the membership of the United Nations. The overarching principle of sovereign equality, as enshrined in Article 2 of the United Nations Charter, requires that the United Nations pay adequate attention to all countries, both large and small. This Policy Brief analyses and underscores why small island economies—as countries in special situations—deserve special attention as the world faces an unprecedented health and economic crisis. The policy brief identifies immediate macroeconomic impacts of the current pandemic with far reaching consequences for sustainable development of these economies.

COVID-19 spares no country

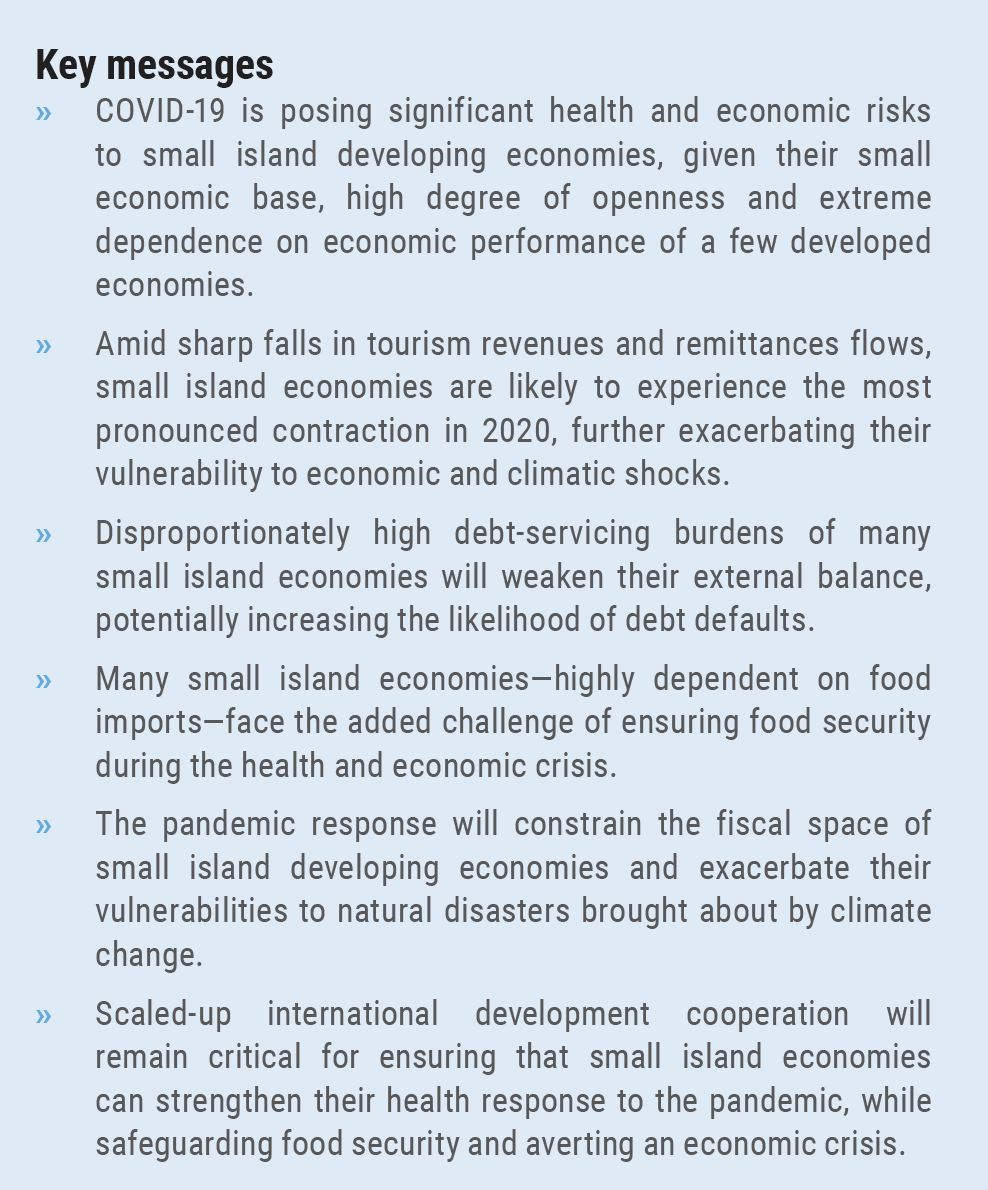

The COVID-19 pandemic is posing an unprecedented health and economic crisis for small island economies. The reported number of COVID-19 related deaths per 100,000 people is higher in these countries compared to other developing country groups and regions, including least developed countries (LDCs) and landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) (Figure 1). The Bahamas, Dominican Republic and Trinidad and Tobago, for example, are experiencing mortality rates as high as many hardest hit countries in Europe. The number of confirmed cases and mortality rates could rise very quickly with the easing of travel restrictions and increased testing and reporting of COVID-19 cases.

The high prevalence of pre-existing health conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and obesity, make populations in small island economies particularly susceptible to COVID-19. Available evidence suggests that people living with these pre-existing conditions are more likely to develop severe symptoms from COVID-19. Compounding their vulnerability, most small island economies lack capacities for detection and treatment of a new disease. The Global Health Security Index (HSI), a comprehensive measurement of a country’s health security and related capabilities, show that small island economies have relatively poorer health capabilities, particularly in prevention, detection, rapid response to epidemics, and ability to treat the sick and protect health workers. A median HSI score of 29—on a scale of 100—underpin significant deficiencies in public health system in these countries, relative to a median score of 54 for high income economies.

The high prevalence of pre-existing health conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and obesity, make populations in small island economies particularly susceptible to COVID-19. Available evidence suggests that people living with these pre-existing conditions are more likely to develop severe symptoms from COVID-19. Compounding their vulnerability, most small island economies lack capacities for detection and treatment of a new disease. The Global Health Security Index (HSI), a comprehensive measurement of a country’s health security and related capabilities, show that small island economies have relatively poorer health capabilities, particularly in prevention, detection, rapid response to epidemics, and ability to treat the sick and protect health workers. A median HSI score of 29—on a scale of 100—underpin significant deficiencies in public health system in these countries, relative to a median score of 54 for high income economies.

Economic consequences of a raging global pandemic

A small and narrow economic base, high degree of openness and significant dependence on few large developed countries make small island economies extremely vulnerable to global economic shocks. These economies are often at the receiving end of global crises, as they are highly dependent on external flows—trade, remittances and external capital and borrowing—compared to other groups of developing countries. Trade, for example, accounts for more than 71% of small island economies’ GDP, compared to 50% for LDCs and 60% for LLDCs.

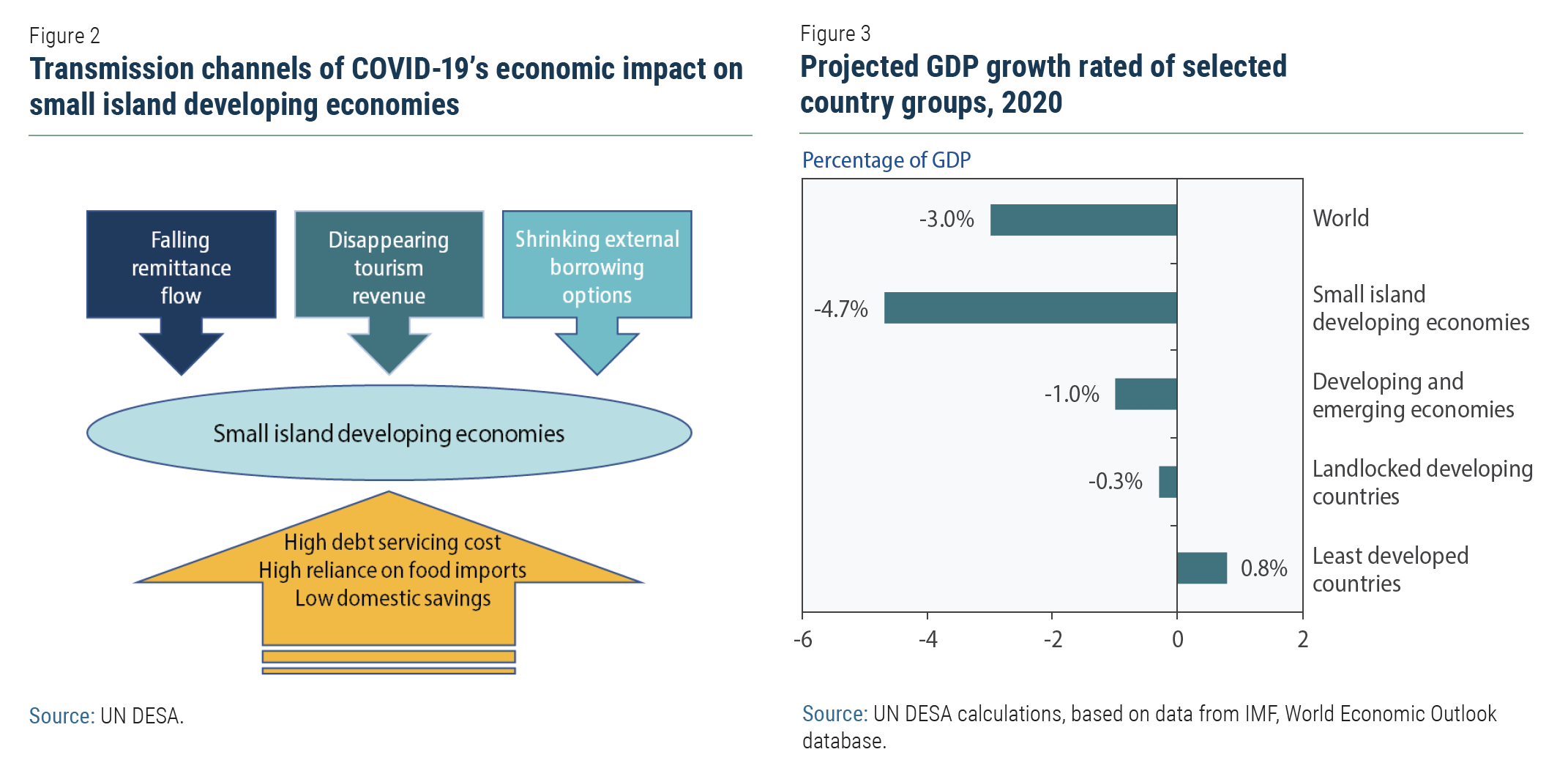

The COVID-19 pandemic is projected to inflict the worst recession since the Great Depression, sparing no country or region in the world. Small island economies will likely experience a severe recession in 2020, pummelled by falling tourism revenue, remittances and capital flows and pressures of high and growing debt servicing costs. The substantial dependence on food imports—50% of all small island economies import more than 80% of their food—is also a major contributing factor (Figure 2).

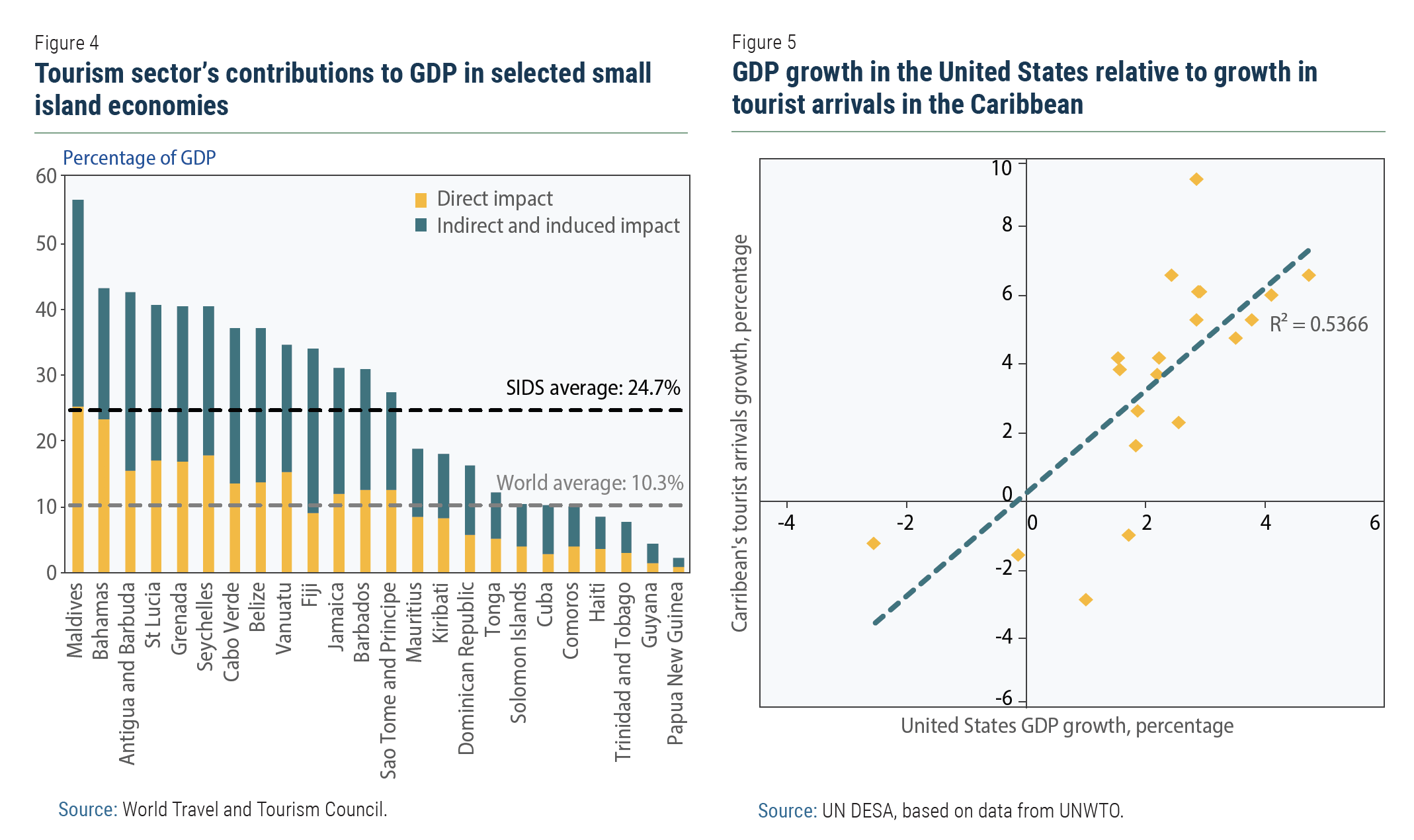

The GDP of small island economies will likely shrink by 4.7% this year, compared to a global contraction of around 3%. Contractions in these economies will be significantly larger than in LDCs and LLDCs (Figure 3), underscoring their extreme vulnerability to global economic shocks. The Bahamas, Maldives, Seychelles and Palau are expected to shrink by 8% or more, making the current crisis the worst in recorded history. The massive economic contraction will lead to significant increases in poverty and undermine the ability of these economies to withstand natural disasters, which have been hitting many of these economies with increasing frequency and intensity. Cyclone Harold, which devastated four Pacific Island nations earlier this month, exposed the extreme vulnerability of these economies as pandemic-induced quarantines and lockdowns impeded the delivery of urgent humanitarian assistance.

The GDP of small island economies will likely shrink by 4.7% this year, compared to a global contraction of around 3%. Contractions in these economies will be significantly larger than in LDCs and LLDCs (Figure 3), underscoring their extreme vulnerability to global economic shocks. The Bahamas, Maldives, Seychelles and Palau are expected to shrink by 8% or more, making the current crisis the worst in recorded history. The massive economic contraction will lead to significant increases in poverty and undermine the ability of these economies to withstand natural disasters, which have been hitting many of these economies with increasing frequency and intensity. Cyclone Harold, which devastated four Pacific Island nations earlier this month, exposed the extreme vulnerability of these economies as pandemic-induced quarantines and lockdowns impeded the delivery of urgent humanitarian assistance.

Pandemic choking economic lifeline

Tourism is the economic lifeline of most small island developing economies. Value added from tourism account for nearly 30% of GDP of these economies. In the case of Maldives or The Bahamas, tourism accounts for more than 40% of GDP (Figure 4). Amid widespread restrictions on international travels and lockdowns at national levels, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) predicts a 20%–30% decline in international tourist arrivals in 2020, dwarfing the 4% decline during 2009. If border closings and restrictions on travel persist beyond one quarter, actual tourism flows could decline by a larger magnitude, dealing a crippling blow to these economies.

Barring a few exceptions, tourism sectors in most small island economies depend on arrivals from a single source country or region. Tourist arrivals from the United States, for example, account for 60%–80% of tourist arrivals for several Caribbean countries, such as The Bahamas and Jamaica. For the Pacific Islands, tourists from Australia and New Zealand account for about half of the total annual tourist arrivals. Meanwhile, for Cabo Verde and the Seychelles, 65%–70% of tourism flows originate from Europe. The excessive dependence on tourist arrivals from a single source make these tourism economies extremely susceptible to downturns in source countries. A very strong and positive correlation between growth rates in tourist arrivals in the Caribbean economies and United States’ GDP growth (Figure 5) show that if the US economy sneezes, many economies in the Caribbean region catch a cold.

Barring a few exceptions, tourism sectors in most small island economies depend on arrivals from a single source country or region. Tourist arrivals from the United States, for example, account for 60%–80% of tourist arrivals for several Caribbean countries, such as The Bahamas and Jamaica. For the Pacific Islands, tourists from Australia and New Zealand account for about half of the total annual tourist arrivals. Meanwhile, for Cabo Verde and the Seychelles, 65%–70% of tourism flows originate from Europe. The excessive dependence on tourist arrivals from a single source make these tourism economies extremely susceptible to downturns in source countries. A very strong and positive correlation between growth rates in tourist arrivals in the Caribbean economies and United States’ GDP growth (Figure 5) show that if the US economy sneezes, many economies in the Caribbean region catch a cold.

The collapse in tourist arrivals not only directly affects income and employment in airlines, ground transport and hotels, but also adversely affects the rest of the economy, including agriculture and construction. Falling tourism, and subsequently, reducing tax revenues, will exacerbate fiscal balances of many small island economies and also reduce the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI), as the tourism sector is typically the largest recipient of FDI.

Fragile external balance

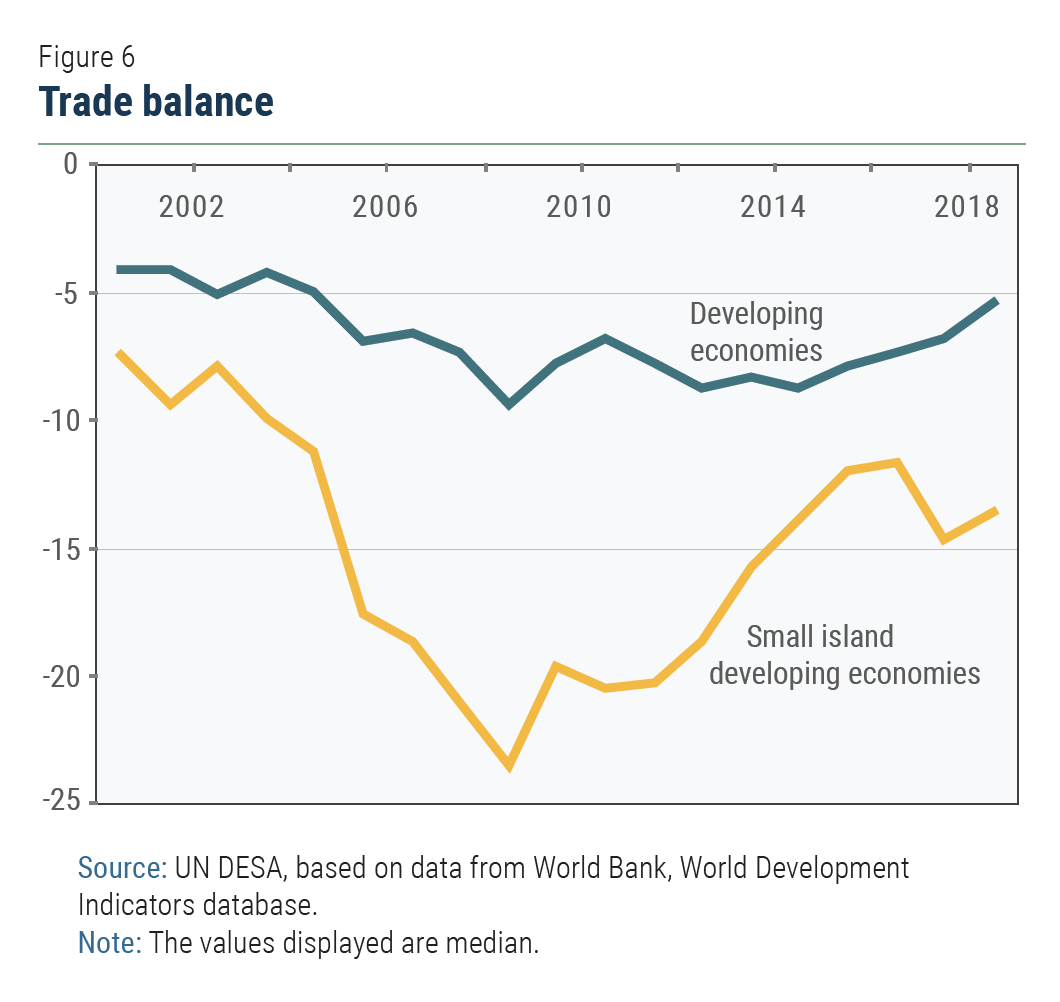

Most small island economies run large trade deficits, with tourism accounting for most of exports, while food, oil and other essentials representing the bulk of imports. Since 2000, the trade deficits of these economies as a group has persistently been at 2-3 times higher than the developing countries’ median (Figure 6), often translating to large and persistent current account deficits. For many of these economies, substantial remittances inflows partly offset current account deficits. The remaining financing gap has been filled by external borrowing, FDI and other flows in the capital account.

While tourism exports are highly volatile and susceptible to downturns in developed economies, the import demand of many small island economies is typically inelastic. This is particularly prominent for economies that are net importers of food, oil and other essential goods. Food imports represent more than 15% of all merchandise imports for a large number of small island economies, which is twice the world average. It is almost 30% for Cabo Verde, Sao Tome and Principe and Samoa. It is also the case that tourism drives much of the food and oil imports in these economies, which may decline amid worldwide travel restrictions. Nevertheless, a shock to global food production and supply chains could translate to higher food price inflation for many small island economies.

Small island economies rely on export revenues to service their debt. Debt servicing, on average, amount to about 15% of the export revenues of small island economies, which is twice the world average. But the Dominican Republic, Jamaica or Papua New Guinea spend as much as a quarter of their export earnings to service their external debt. If the global slowdown significantly reduces export earnings of these economies, their debt service burdens—both as a percentage of GDP and exports—will increase sharply, potentially increasing the risks of a default on external debt.

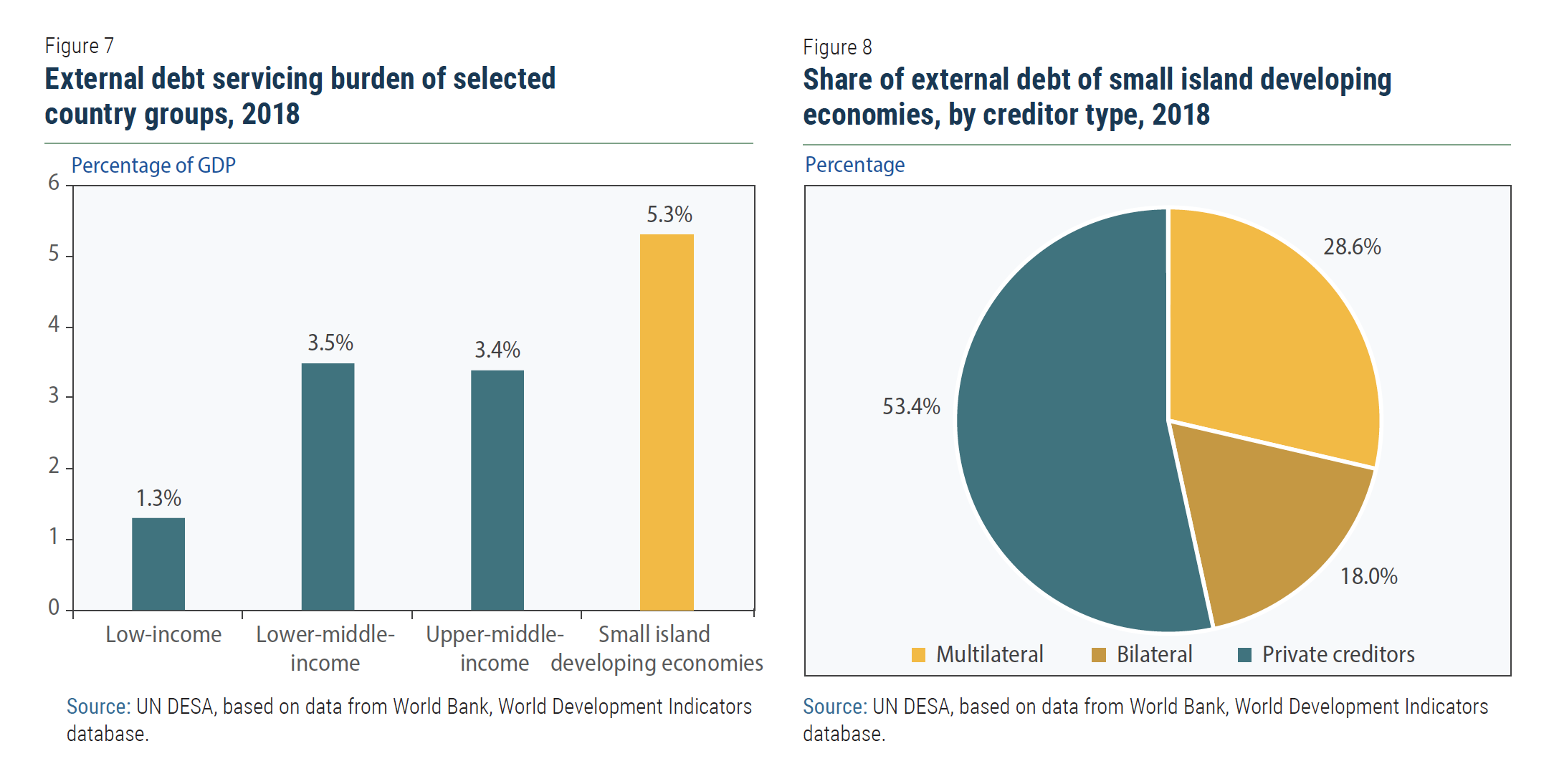

As the COVID-19 crisis simultaneously shrinks tourism revenues and remittance flows, outflows to service debt and pay for food imports will remain constant or even rise. In a typical year, the external debt servicing burden of small island economies as a group is 5.3% of their GDP. This is more than four times higher than the debt servicing burden of low-income countries and higher than any other country group, including upper middle-income countries (Figure 7). Importantly, average external debt service burden for small island economies masks a stark disparity between the economies, with the Caribbean countries facing much higher debt service burdens.

Many small island economies, particularly the Caribbean economies largely borrow from private creditors to finance their chronic and large trade and current account deficits (Figure 8). This results in higher borrowing costs—higher than that available from multilateral and bilateral sources—and pay large risk premiums because of their chronic trade and current account deficits, relatively low level of international reserves and their high vulnerability to natural disasters.

Many small island economies, particularly the Caribbean economies largely borrow from private creditors to finance their chronic and large trade and current account deficits (Figure 8). This results in higher borrowing costs—higher than that available from multilateral and bilateral sources—and pay large risk premiums because of their chronic trade and current account deficits, relatively low level of international reserves and their high vulnerability to natural disasters.

Leaving no country behind

The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for small island economies will be both devastating and far-reaching. The crisis will significantly weaken the capacities of these countries to withstand a simultaneous crisis, should a cyclone or hurricane hit any of these economies this year or next—a possibility that cannot be ruled out completely. Many countries in the Caribbean and the Pacific are still recovering from devastating hurricanes during the past couple of years. Against the backdrop of the crippling effects of the pandemic, several small island economies are enacting tax relief for affected sectors and firms, especially the small businesses, and increasing targeted social spending, including unemployment benefits and prioritizing public investments. While several small island economies have some social protection systems in place, there are many, especially the Pacific economies, lack social protection. Strengthening social protection systems, and enhancing poverty eradication and social inclusion policies, will be essential to preserve the progress made towards the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. Fiscal efforts are however constrained by limited fiscal space. Many of these economies face additional challenge of mobilizing sufficient fiscal buffers to deal with frequent natural disasters. Notwithstanding these challenges, small island economies in the Caribbean have so far announced a stimulus package estimated at around 1%–4% of GDP, which will clearly be insufficient for mitigating the catastrophic impacts of a twin health and economic crisis.

The global commitment to leave no one behind must extend to leaving no country behind, especially to most vulnerable countries, which include small island economies that are also least developed countries. The pandemic puts the cardinal commitment of solidarity to test. International development cooperation is at the heart of reducing risk, enabling recovery and building resilience. The international community must come forward to prevent the economic devastation of small island economies. There should be concerted international efforts to:

- Ensure that small island economies can scale-up testing and treatment and have uninterrupted access to critical medical supplies, not only to fight the pandemic but also for contingencies, should they be hit by a natural disaster during the pandemic.

- Bolster food security of these small island economies, increasing supply of grains, meat, dairy and other critical food items to prevent food price inflation and reduce the likelihood of rising poverty and hunger. It would be critical to build and maintain a buffer food stock for these economies in the event of sudden disruptions in the global supply chain.

- Limit debt servicing costs of these small island economies—through a combination of debt relief, forbearance and debt swaps, ensuring that these economies do not experience a balance of payment crisis during this very difficult time.

- Expand concessional financing for the small island economies, LDCs, and other vulnerable developing countries to complement domestically financed stimulus packages, which will clearly be inadequate for addressing the magnitude of the crisis. Many of these economies will need fiscal stimulus—as large as 10% or more of their GDP—to minimize the cataclysmic impact of the current crisis.

- Establish and operationalize a dedicated debt relief mechanism for small island economies, taking into account their extreme vulnerability to economic and climate shocks, to ensure long-term debt sustainability and foster investments in sustainable development in small island economies.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations