A decade has passed since the initial onset of the global financial crisis. Following a protracted period of sub-par growth, the global economy has strengthened as the effects of cyclical headwinds and crisis-related legacies dissipate. According to the United Nations’ World Economic Situation and Prospects 2018 report, global GDP growth accelerated to 3.0 per cent in 2017, marking the fastest pace of expansion in six years. At the same time, inflationary pressures remain subdued and there are no signs of overheating in most economies.

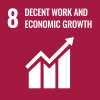

While the short-term global outlook has improved, pockets of financial vulnerabilities have emerged. The prolonged period of abundant global liquidity and low borrowing costs has distorted investors’ perception of risk, fuelling a global search for yield. This has had a disproportionately large effect on emerging economies. Since the crisis, many of these economies have experienced large and volatile capital flows, rapid credit and asset price growth, and a significant increase in debt levels. According to the Bank for International Settlements, aggregate debt levels of non-financial emerging market corporates exceeded 100 per cent of GDP in 2017, up from 60 per cent in 2007. Among the major emerging economies, China has seen the sharpest increase in corporate debt, with debt levels standing at over 160 per cent of GDP in 2017 (Figure 1). Growth in household debt levels and residential property prices has also escalated, most notably in Asia. Policymakers in emerging economies thus face the difficult task of preserving financial stability while sustaining the growth momentum. The global financial crisis highlighted the massive cost of financial boom and bust cycles, and the importance of containing the buildup of systemic risks. In this context, macroprudential measures are increasingly becoming an integral part of the policy toolkit of many countries, complementing conventional monetary and fiscal policies, and microprudential regulation. Macroprudential policies are aimed at containing the build-up of systemic vulnerabilities and increasing the resilience of the financial system to shocks. The growing preference of policymakers to deploy macroprudential tools as a pre-emptive response to financial imbalances is motivated by several factors. First, macroprudential instruments allow policymakers to target sector-specific vulnerabilities. In comparison, policy interest rates are often regarded as a blunt tool in managing financial risks that are concentrated in a particular sector. They impact all asset prices and activity in the economy as a whole, much of which may be in a different phase of the economic cycle than the targeted sector. Second, macroprudential policies allow financial regulators to move beyond a pure microprudential approach which focuses on risks at the level of individual financial institutions, to also address risks in the financial system as a whole.

While the short-term global outlook has improved, pockets of financial vulnerabilities have emerged. The prolonged period of abundant global liquidity and low borrowing costs has distorted investors’ perception of risk, fuelling a global search for yield. This has had a disproportionately large effect on emerging economies. Since the crisis, many of these economies have experienced large and volatile capital flows, rapid credit and asset price growth, and a significant increase in debt levels. According to the Bank for International Settlements, aggregate debt levels of non-financial emerging market corporates exceeded 100 per cent of GDP in 2017, up from 60 per cent in 2007. Among the major emerging economies, China has seen the sharpest increase in corporate debt, with debt levels standing at over 160 per cent of GDP in 2017 (Figure 1). Growth in household debt levels and residential property prices has also escalated, most notably in Asia. Policymakers in emerging economies thus face the difficult task of preserving financial stability while sustaining the growth momentum. The global financial crisis highlighted the massive cost of financial boom and bust cycles, and the importance of containing the buildup of systemic risks. In this context, macroprudential measures are increasingly becoming an integral part of the policy toolkit of many countries, complementing conventional monetary and fiscal policies, and microprudential regulation. Macroprudential policies are aimed at containing the build-up of systemic vulnerabilities and increasing the resilience of the financial system to shocks. The growing preference of policymakers to deploy macroprudential tools as a pre-emptive response to financial imbalances is motivated by several factors. First, macroprudential instruments allow policymakers to target sector-specific vulnerabilities. In comparison, policy interest rates are often regarded as a blunt tool in managing financial risks that are concentrated in a particular sector. They impact all asset prices and activity in the economy as a whole, much of which may be in a different phase of the economic cycle than the targeted sector. Second, macroprudential policies allow financial regulators to move beyond a pure microprudential approach which focuses on risks at the level of individual financial institutions, to also address risks in the financial system as a whole.

Emerging economies’ use of macroprudential measures

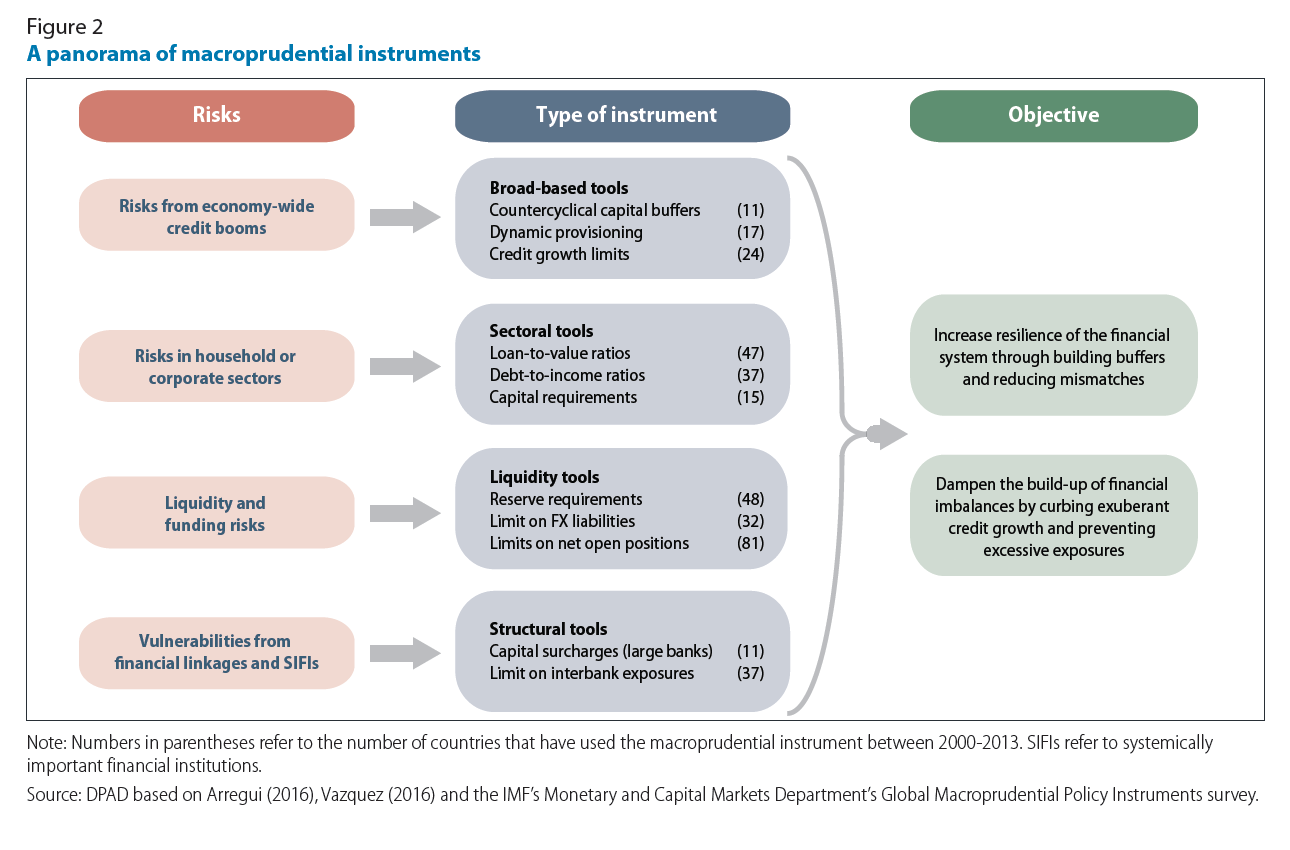

Figure 2 lays out different types of systemic risks that policymakers may face and the corresponding macroprudential tools that have been deployed to mitigate these risks. Several studies have shown that the use of macroprudential instruments has been more widespread in emerging economies than in developed countries (Cerutti et al., 2015; Galati and Moessner, 2017). Some of these economies increased the usage of macroprudential measures in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, amid heightened concerns over the surge in capital flow volatility and its disruptive effects on domestic liquidity and financial stability.  Given that macroprudential policies are still largely in the experimental stage, policymakers have continued to fine-tune existing measures in response to recent economic and financial developments. In 2017, the rapid rise in real estate prices prompted the Republic of Korea to lower the maximum loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios for property purchases in selected regions. For homeowners with more than three homes, a capital gains tax of 20 percentage points on top of the existing levy was also imposed. These recent measures were also aimed at reining in household debt, which at 90 per cent of GDP is one of the highest in Asia. In China, policymakers are prioritizing the reduction of corporate debt, particularly debt of state-owned enterprises. In efforts to lower default risks, the debt-to-equity swap programme was accelerated, while new restrictions were recently imposed on banks’ acquisition of entrusted loans, which constitute riskier assets. To reduce speculation in the property sector, several major cities imposed tighter purchase restrictions, including higher mortgage down payments and a ban on the resale of new homes within a specified time period. In efforts to mitigate large capital outflows, the authorities also announced limits on foreign acquisitions and investment abroad in specific sectors where corporates are deemed to have excessive debt, including hotels and real estate. In Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China, the authorities further tightened regulations on mortgage loans in 2017 in response to soaring property prices. These measures included lowering the maximum loan-to-value ratio for borrowers with more than one pre-existing mortgage and lowering the debt service ratio for borrowers whose incomes are mainly derived from outside of Hong Kong SAR. In contrast, a few countries recently loosened existing macroprudential measures to support economic activity. Among Latin American countries, Brazil lowered reserve requirements for banks in order to stimulate credit growth. Argentina undertook a similar measure, while also relaxing several capital flow restrictions, including ending the holding period for repatriation of foreign capital. Meanwhile, Turkey eased regulations on consumer loans, helping to boost credit growth.

Given that macroprudential policies are still largely in the experimental stage, policymakers have continued to fine-tune existing measures in response to recent economic and financial developments. In 2017, the rapid rise in real estate prices prompted the Republic of Korea to lower the maximum loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios for property purchases in selected regions. For homeowners with more than three homes, a capital gains tax of 20 percentage points on top of the existing levy was also imposed. These recent measures were also aimed at reining in household debt, which at 90 per cent of GDP is one of the highest in Asia. In China, policymakers are prioritizing the reduction of corporate debt, particularly debt of state-owned enterprises. In efforts to lower default risks, the debt-to-equity swap programme was accelerated, while new restrictions were recently imposed on banks’ acquisition of entrusted loans, which constitute riskier assets. To reduce speculation in the property sector, several major cities imposed tighter purchase restrictions, including higher mortgage down payments and a ban on the resale of new homes within a specified time period. In efforts to mitigate large capital outflows, the authorities also announced limits on foreign acquisitions and investment abroad in specific sectors where corporates are deemed to have excessive debt, including hotels and real estate. In Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China, the authorities further tightened regulations on mortgage loans in 2017 in response to soaring property prices. These measures included lowering the maximum loan-to-value ratio for borrowers with more than one pre-existing mortgage and lowering the debt service ratio for borrowers whose incomes are mainly derived from outside of Hong Kong SAR. In contrast, a few countries recently loosened existing macroprudential measures to support economic activity. Among Latin American countries, Brazil lowered reserve requirements for banks in order to stimulate credit growth. Argentina undertook a similar measure, while also relaxing several capital flow restrictions, including ending the holding period for repatriation of foreign capital. Meanwhile, Turkey eased regulations on consumer loans, helping to boost credit growth.

Evidence on the effectiveness of macroprudential measures

Recent anecdotal evidence suggests that macroprudential measures have had the intended effects on the financial sector in several countries. In 2017, China’s outbound direct investment contracted for the first time since the crisis, while house prices grew at the slowest pace in almost two years. In Singapore, a series of macroprudential tightening measures to curb speculation and rein in an overheated property market contributed to a 15-quarter consecutive decline in private residential property prices. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s recent sovereign credit rating upgrade was in part attributed to the effectiveness of macroprudential measures in mitigating capital flow volatility and curbing the rise in corporate external debt. While still in its infancy, there is a growing body of empirical literature that examines the effectiveness of macroprudential policies in containing systemic risks. These studies confirm the anecdotal evidence, and show that for many countries macroprudential instruments have played a role in mitigating financial vulnerabilities, thus contributing to greater financial stability. For emerging economies, several studies have found that macroprudential measures have helped to reduce procyclical pressures in credit markets. In particular, limits on loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios have visibly dampened credit expansion in emerging Asian and Latin American economies (Zhang and Zoli, 2014; Gambacorta and Murcia, 2017). In addition, the use of capital controls on banking inflows has also been associated with lower credit growth in emerging economies (Akinci and Olmstead-Rumsey, 2015). The ultimate objective of macroprudential policies is to reduce the likelihood of financial crises, and therefore support stable and firm macroeconomic conditions. In this aspect, Boar et al. (2017) found that countries that use macroprudential tools more actively tend to experience stronger and less volatile economic growth. From a microeconomic perspective, Altunbas et al. (2017) showed for a large sample of developed and emerging economies that the tightening of macroprudential measures reduced bank risk taking and the probability of bank default. In addition, the literature highlights several specific findings that may offer some useful insights for policymakers going forward. First, the effectiveness of macroprudential policies depends on prevailing domestic and external conditions. Notably, many of these instruments tend to work better in the boom rather than in the bust phase of the financial cycle (Cerutti et al., 2015). Several studies have highlighted the importance of strong institutional frameworks with a clear accountability structure in determining the success of macroprudential policies in a country (IMF/FSB/BIS, 2016). Second, macroprudential instruments display varying degrees of success when used to address different types of systemic risks. This underscores the importance for policymakers to accurately identify and understand the nature of the risk at hand in order to deploy the appropriate tools. Akinci and Olmstead-Rumsey (2015) showed that compared to the use of broad-based tools, targeted measures seem to be more effective in restraining credit growth in a specific sector, such as the housing market. In Latin America, policies aimed at enhancing financial sector resilience (capital requirements, liquidity ratios) have more delayed effects than those aimed at dampening the credit cycle (Gambacorta and Murcia, 2017). Meanwhile in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, Vandenbussche et al. (2015) showed that capital measures (minimum capital adequacy ratio, maximum ratio of lending to households to share capital) and nonstandard liquidity measures (marginal reserve requirements on foreign funding) were much more effective than reserve requirements in containing house price inflation. Third, macroprudential policies tend to be more effective when complemented with other tools. Lee et al. (2017) stressed the importance of coordinating macroprudential measures with appropriate monetary, fiscal and other financial policies in order to enhance their effectiveness. In particular, the simultaneous use of several measures helps to address potential leakages or circumventions, thus increasing the likelihood of achieving the intended objective (Erdem et al., 2017). Meanwhile, several studies on Latin American economies, including Brazil and Colombia, suggest that the effectiveness of reserve requirements and dynamic provisioning depends on the contemporaneous use of traditional monetary policy instruments (Barroso et al., 2017; Gómez et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The financial globalization of the past few decades has increased the interdependencies between economies worldwide, creating both benefits and new risks. With this in mind, emerging economies need to constantly review their macroprudential policy framework to ensure that existing measures help preserve financial stability. The rapidly expanding literature on this subject can enhance policymakers’ understanding of how the various macroprudential instruments operate under different circumstances and how they interact with other policies.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations