As the world enters the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is abundantly clear that this is a crisis of monumental proportions, where millions of lives have been lost and the human and economic toll has been unprecedented. Recovery efforts so far have been uneven, inequitable and insufficiently geared towards achieving sustainable development. The current crisis is threatening decades of development gains, further delaying the urgent transition to greener, more equal and inclusive economies, and throwing progress on the SDGs even further off track. Had the paradigm shift originally envisioned in the SDGs been fully embraced, the world would have been better prepared to face the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a mirror for the world. It reflects deeply rooted problems in our societies: inadequate governance capacities to address the consequences of the pandemic, insufficient social protection, weak public health systems and inadequate health coverage, structural inequalities, environmental degradation, unsustainable consumption and production and climate change. Further, a lack of investment in data and weaknesses in data and information systems in even the most developed systems meant many countries were left to fly blind amidst parallel social, health and economic crises that have engulfed the world and disrupted progress on the SDGs across the globe. The world is at a critical juncture in human history. The decisions we make and actions we take today will have momentous consequences for future generations. Lessons learned from the pandemic will help us rise to current and future challenges. This article uses the latest available data and estimates from The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021 to reveal the devastating impacts of the crisis on the SDGs and point out areas that require urgent and coordinated action.

As the world enters the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is abundantly clear that this is a crisis of monumental proportions, where millions of lives have been lost and the human and economic toll has been unprecedented. Recovery efforts so far have been uneven, inequitable and insufficiently geared towards achieving sustainable development. The current crisis is threatening decades of development gains, further delaying the urgent transition to greener, more equal and inclusive economies, and throwing progress on the SDGs even further off track. Had the paradigm shift originally envisioned in the SDGs been fully embraced, the world would have been better prepared to face the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a mirror for the world. It reflects deeply rooted problems in our societies: inadequate governance capacities to address the consequences of the pandemic, insufficient social protection, weak public health systems and inadequate health coverage, structural inequalities, environmental degradation, unsustainable consumption and production and climate change. Further, a lack of investment in data and weaknesses in data and information systems in even the most developed systems meant many countries were left to fly blind amidst parallel social, health and economic crises that have engulfed the world and disrupted progress on the SDGs across the globe. The world is at a critical juncture in human history. The decisions we make and actions we take today will have momentous consequences for future generations. Lessons learned from the pandemic will help us rise to current and future challenges. This article uses the latest available data and estimates from The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021 to reveal the devastating impacts of the crisis on the SDGs and point out areas that require urgent and coordinated action.

Years, or even decades, of progress have been halted or reversed by the pandemic

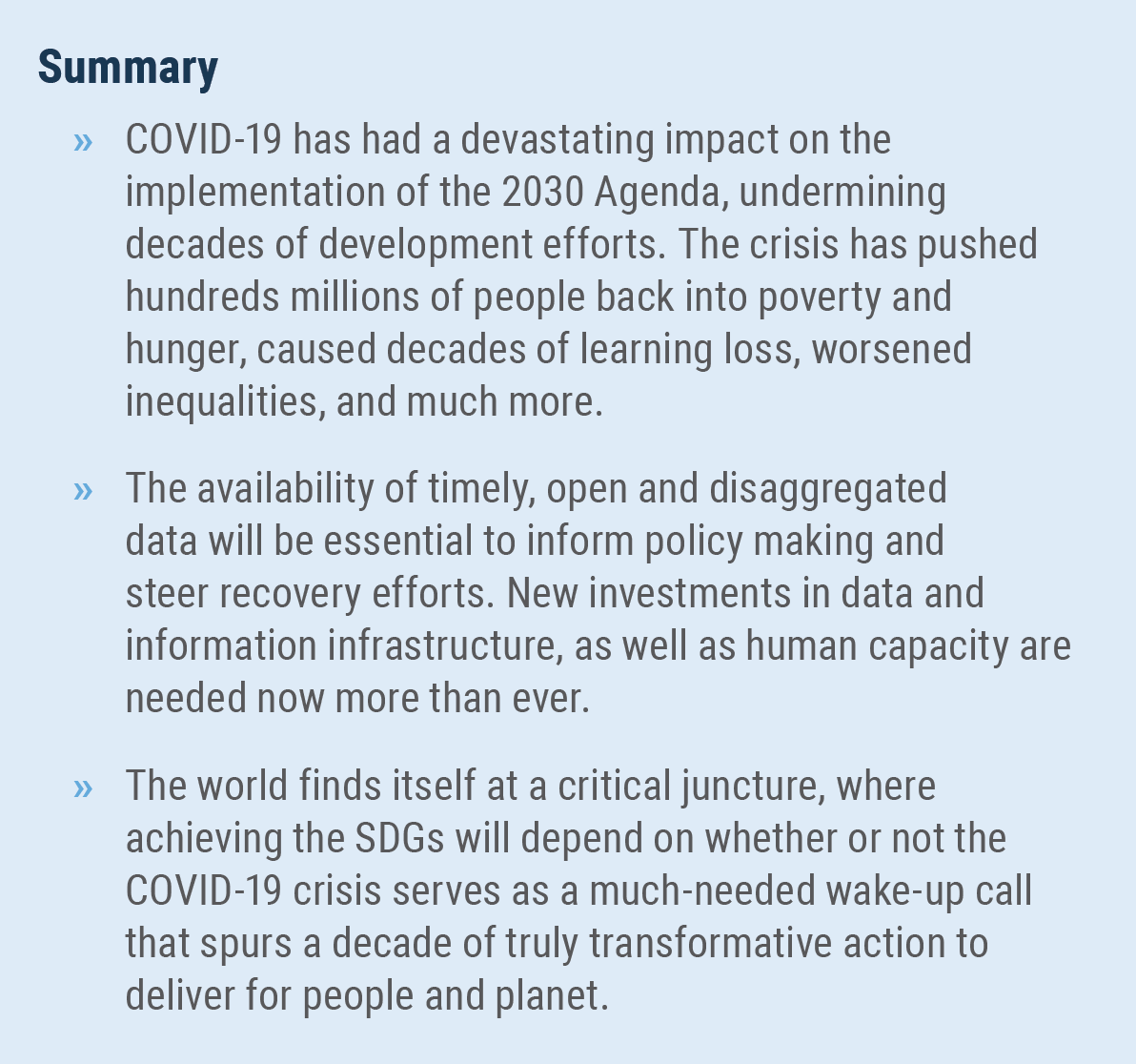

Significant impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic are reverberating across the Goals, translating to catastrophic effects on people’s lives and livelihoods and on efforts to achieve the 2030 Agenda. The extreme poverty rate rose for the first time since 1998, from 8.4 per cent in 2019 to 9.5 per cent in 2020, undoing the progress made since 2016. This means that the pandemic pushed around 100 million people back into extreme poverty in 2020. Based on current projections, the global poverty rate is expected to be 7 per cent in 2030 (around 600 million people), missing the target of eradicating poverty unless immediate and substantial policy actions are taken.  The pandemic has posed additional threats to global food security and nutrition, triggered by disruptions in food supply chains, income losses, widening social inequalities, changes in the way people engage and interact with the food system and price hikes. Between 720 and 811 million people in the world faced hunger in 2020, an increase of as many as 161 million from 2019. The crisis has disrupted economic activities around the world and caused the worst recession since the Great Depression. In 2020, 8.8 per cent of global working hours were lost (relative to the fourth quarter of 2019), equivalent to 255 million full-time jobs – about four times the number lost during the global financial crisis in 2007-2009. The pandemic has halted or reversed progress in health and poses major threats beyond the disease itself. About 90 per cent of countries are still reporting one or more disruptions to essential health services. In 2020, 23 million children around the world missed out on life-saving vaccines – 3.7 million more than in 2019. Available data from a few countries show that the pandemic has shortened life expectancy.

The pandemic has posed additional threats to global food security and nutrition, triggered by disruptions in food supply chains, income losses, widening social inequalities, changes in the way people engage and interact with the food system and price hikes. Between 720 and 811 million people in the world faced hunger in 2020, an increase of as many as 161 million from 2019. The crisis has disrupted economic activities around the world and caused the worst recession since the Great Depression. In 2020, 8.8 per cent of global working hours were lost (relative to the fourth quarter of 2019), equivalent to 255 million full-time jobs – about four times the number lost during the global financial crisis in 2007-2009. The pandemic has halted or reversed progress in health and poses major threats beyond the disease itself. About 90 per cent of countries are still reporting one or more disruptions to essential health services. In 2020, 23 million children around the world missed out on life-saving vaccines – 3.7 million more than in 2019. Available data from a few countries show that the pandemic has shortened life expectancy.  There is a risk of a generational catastrophe regarding children’s learning and well-being. One year into the crisis, two in three students were still affected by full or partial school closures. The pandemic is projected to cause an additional 101 million children in primary and lower secondary school to fall below the minimum reading proficiency threshold in 2020, wiping out two decades of education gains.

There is a risk of a generational catastrophe regarding children’s learning and well-being. One year into the crisis, two in three students were still affected by full or partial school closures. The pandemic is projected to cause an additional 101 million children in primary and lower secondary school to fall below the minimum reading proficiency threshold in 2020, wiping out two decades of education gains.

The crisis has exposed and intensified inequalities within and among countries

Not only are the poorest and most vulnerable people at a greater risk of becoming infected by the virus, they have also borne the brunt of the adverse social impacts and economic fallout from the pandemic. COVID-19 disproportionately affects women, older persons, the poor, refugees and migrants, children and youth, persons with disabilities and a broad range of vulnerable groups due to their specific health and socioeconomic circumstances. Moreover, the collateral effects of the pandemic resulting from the global economic downturn, social isolation and movement restrictions inequitably affect those who are already marginalized.  Available age-disaggregated national data showed that people aged 65 and over comprised close to 80 per cent of all COVID-19 deaths, even though only 14 per cent of confirmed COVID-19 cases were for that age group. Violence against women and girls was at unacceptably high levels before the pandemic. Nearly one in three women (736 million) have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15, usually by an intimate partner. The pandemic has intensified these levels. The pandemic is adding to the burden of unpaid work of women, who already spend about 2.5 times as many hours on unpaid domestic and care work as men in an average day. In addition, women were more likely than men to drop out of the labour force. This further increased longstanding gender gaps in labour force participation rates and actually reversed gains in many countries. The costs of lower participation of women in the labour force can have significant implications going forward. The pandemic is intensifying children’s risk of exploitation, including child marriage and child labour. Child marriage, on the decline in recent years, is expected to increase with up to 10 million more girls at risk over the next decade, in addition to the 100 million who were projected to become child brides before the pandemic. At the start of 2020, the number of children engaged in child labour totalled 160 million – representing the first increase in two decades. The impacts of COVID-19 threaten to push an additional 8.9 million children into child labour by the end of 2022, as families send children out to work in response to job and income losses. In 2020, 1.6 billion informal economy workers were significantly affected by lockdown measures and/or were working in the hardest-hit sectors. Among them, women were overrepresented in so-called high-risk sectors: 42 per cent of women workers were engaged in those sectors, compared with 32 per cent of men. These workers face a high risk of falling into poverty and will experience greater challenges in regaining their livelihoods during the recovery. In addition, the impacts of COVID-19 have disproportionately affected low-income households and those in the informal sector, further worsening the plight of more than 1 billion slum dwellers and those living in informal settlements and further marginalizing those already vulnerable.

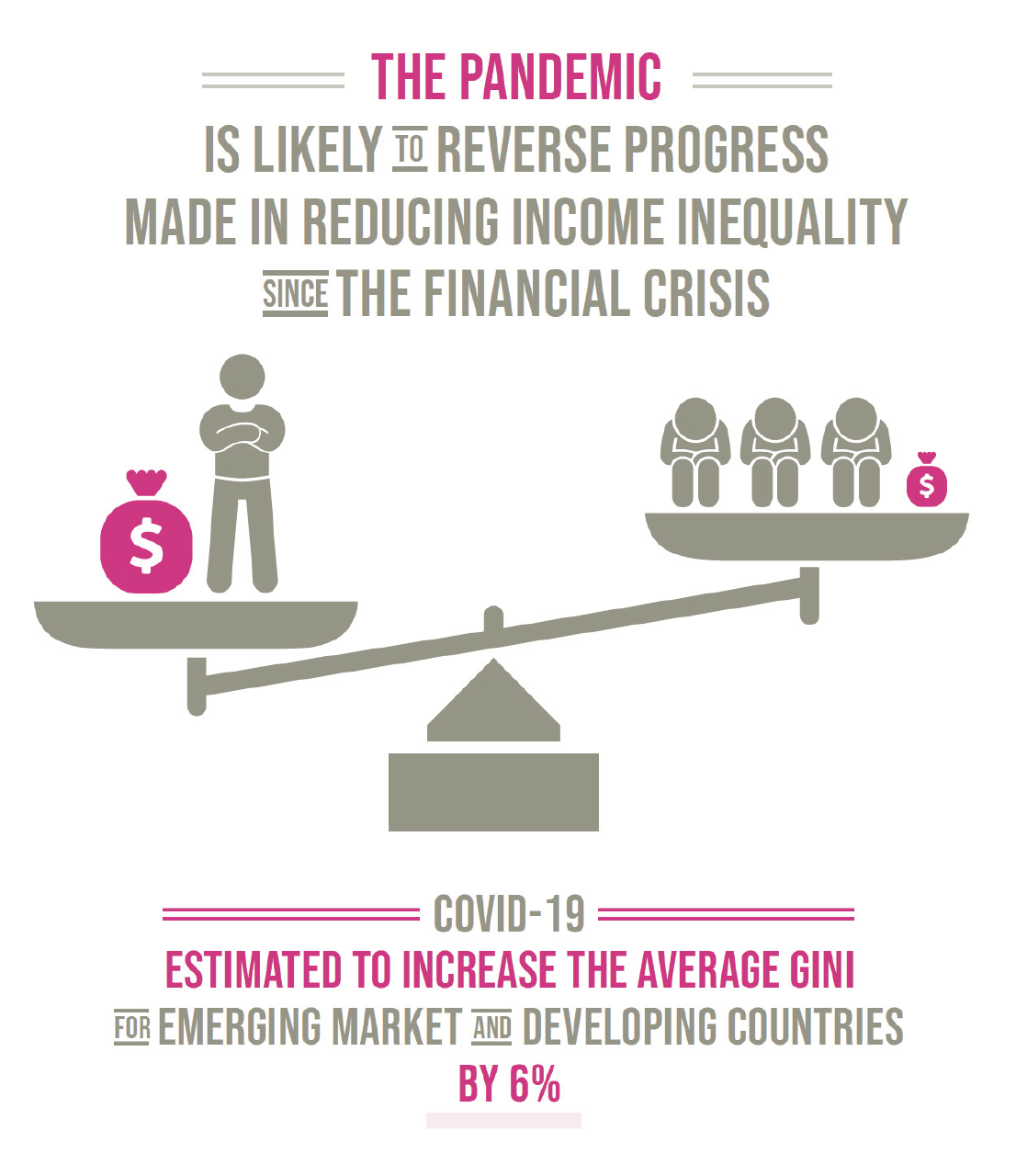

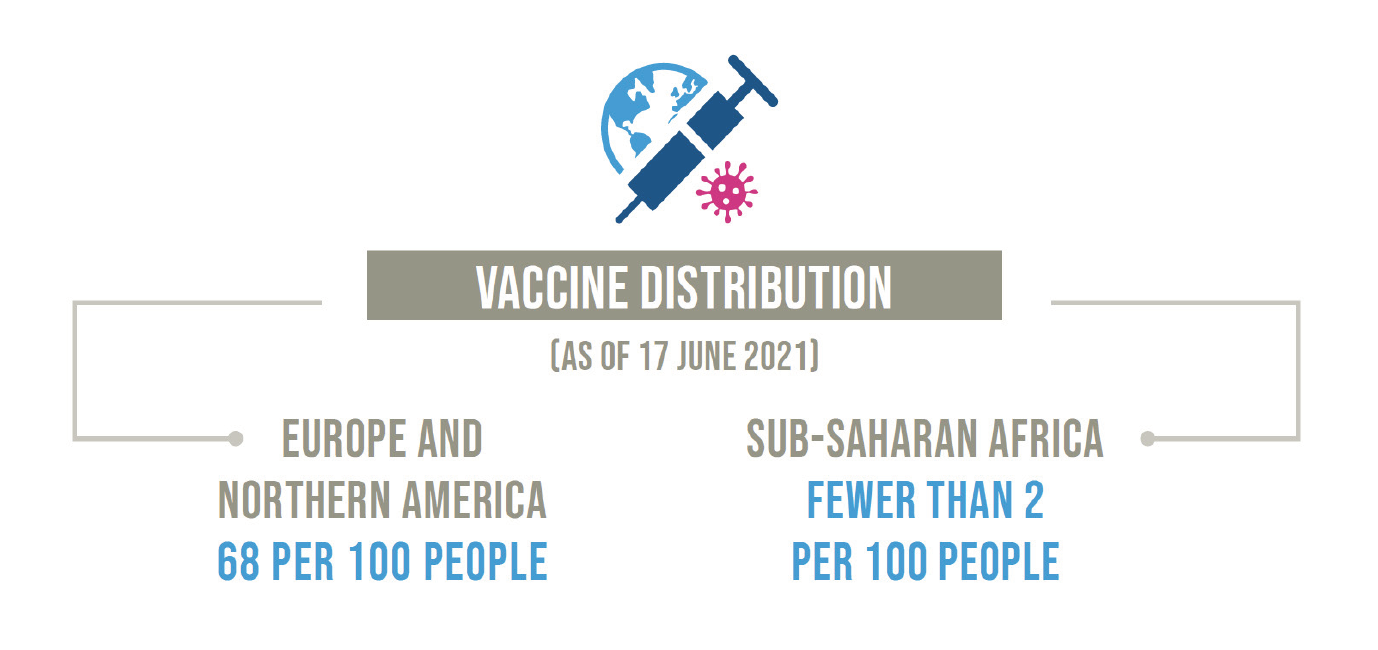

Available age-disaggregated national data showed that people aged 65 and over comprised close to 80 per cent of all COVID-19 deaths, even though only 14 per cent of confirmed COVID-19 cases were for that age group. Violence against women and girls was at unacceptably high levels before the pandemic. Nearly one in three women (736 million) have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15, usually by an intimate partner. The pandemic has intensified these levels. The pandemic is adding to the burden of unpaid work of women, who already spend about 2.5 times as many hours on unpaid domestic and care work as men in an average day. In addition, women were more likely than men to drop out of the labour force. This further increased longstanding gender gaps in labour force participation rates and actually reversed gains in many countries. The costs of lower participation of women in the labour force can have significant implications going forward. The pandemic is intensifying children’s risk of exploitation, including child marriage and child labour. Child marriage, on the decline in recent years, is expected to increase with up to 10 million more girls at risk over the next decade, in addition to the 100 million who were projected to become child brides before the pandemic. At the start of 2020, the number of children engaged in child labour totalled 160 million – representing the first increase in two decades. The impacts of COVID-19 threaten to push an additional 8.9 million children into child labour by the end of 2022, as families send children out to work in response to job and income losses. In 2020, 1.6 billion informal economy workers were significantly affected by lockdown measures and/or were working in the hardest-hit sectors. Among them, women were overrepresented in so-called high-risk sectors: 42 per cent of women workers were engaged in those sectors, compared with 32 per cent of men. These workers face a high risk of falling into poverty and will experience greater challenges in regaining their livelihoods during the recovery. In addition, the impacts of COVID-19 have disproportionately affected low-income households and those in the informal sector, further worsening the plight of more than 1 billion slum dwellers and those living in informal settlements and further marginalizing those already vulnerable.  The Gini coefficient is expected to increase by 6 per cent for emerging markets and developing countries, reversing the fall in inequality since the global financial crisis in 2007–2009. Vast inequities exist in vaccine distribution: as of 17 June 2021, around 68 vaccines were administered for every 100 people in Europe and Northern America compared with fewer than 2 in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Gini coefficient is expected to increase by 6 per cent for emerging markets and developing countries, reversing the fall in inequality since the global financial crisis in 2007–2009. Vast inequities exist in vaccine distribution: as of 17 June 2021, around 68 vaccines were administered for every 100 people in Europe and Northern America compared with fewer than 2 in sub-Saharan Africa.

The climate, biodiversity and pollution crises persist

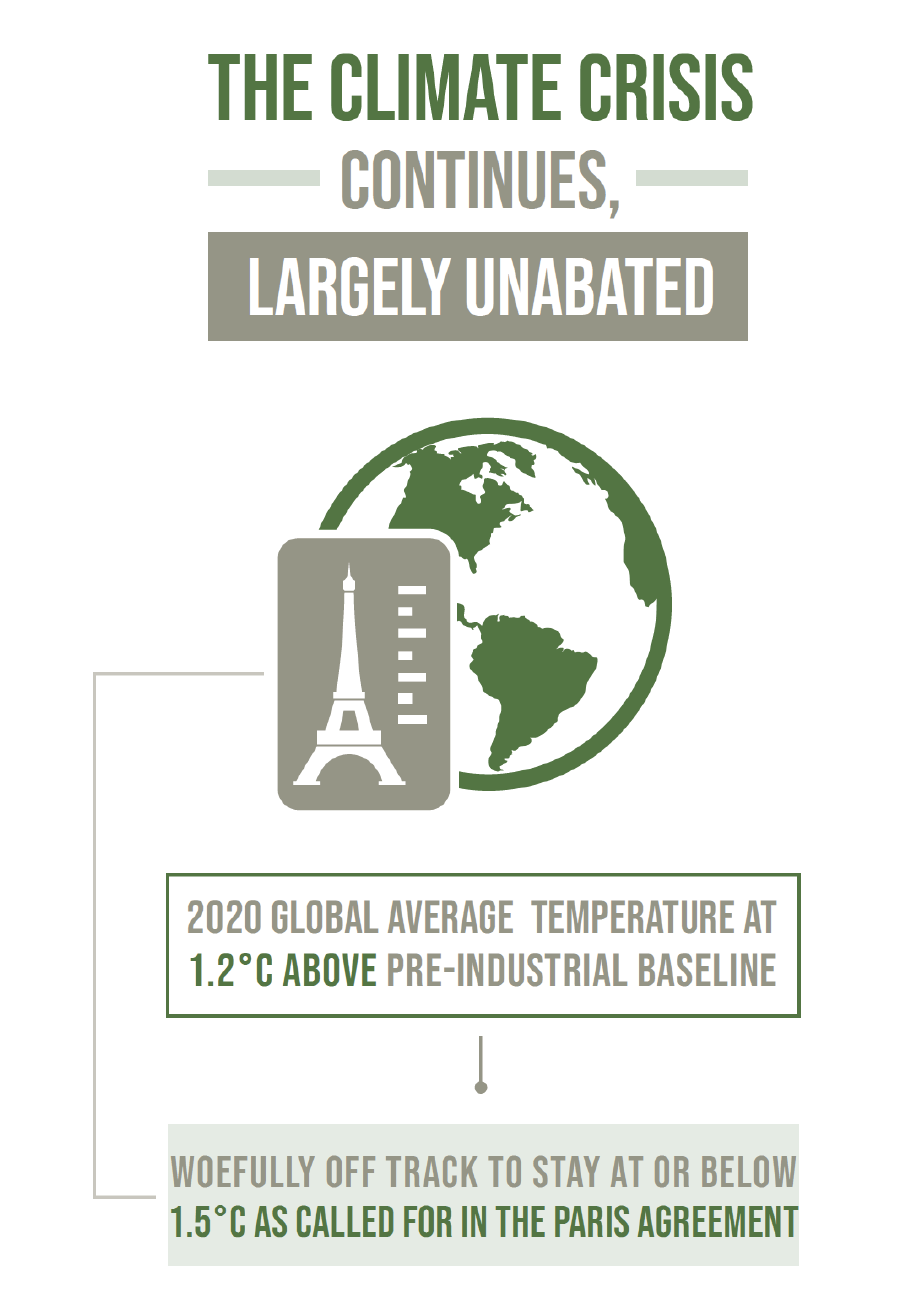

Despite a pandemic-related economic slowdown, the climate crisis continues largely unabated. Even with a temporary reduction in human activities, which resulted in a dip in emissions, concentrations of greenhouse gases continued to increase in 2020, reaching new record highs. The year 2020 ended as one of the three warmest years on record.  Human activities are causing biodiversity to decline faster than at any other time in human history. Even before the pandemic, the world fell short of its 2020 targets to halt biodiversity loss. Currently, more than one quarter of species assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List are threatened with extinction, driven by agricultural and urban development; unsustainable harvesting through hunting, fishing, trapping and logging; and invasive alien species. Similarly, the sustainability of our oceans is under severe threat from acidification, eutrophication, overfishing and pollution, thereby threatening the livelihoods of over 3 billion people reliant on this vast and essential resource. Around the world, the unsustainable use of natural resources is having a devastating impact on our planet. Globally, 1 million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute and 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are thrown away each year. Our actions have translated into the global material footprint increasing by 70 per cent between 2000 and 2017.

Human activities are causing biodiversity to decline faster than at any other time in human history. Even before the pandemic, the world fell short of its 2020 targets to halt biodiversity loss. Currently, more than one quarter of species assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List are threatened with extinction, driven by agricultural and urban development; unsustainable harvesting through hunting, fishing, trapping and logging; and invasive alien species. Similarly, the sustainability of our oceans is under severe threat from acidification, eutrophication, overfishing and pollution, thereby threatening the livelihoods of over 3 billion people reliant on this vast and essential resource. Around the world, the unsustainable use of natural resources is having a devastating impact on our planet. Globally, 1 million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute and 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are thrown away each year. Our actions have translated into the global material footprint increasing by 70 per cent between 2000 and 2017.

The means of implementation to enact the SDGs have been negatively affected

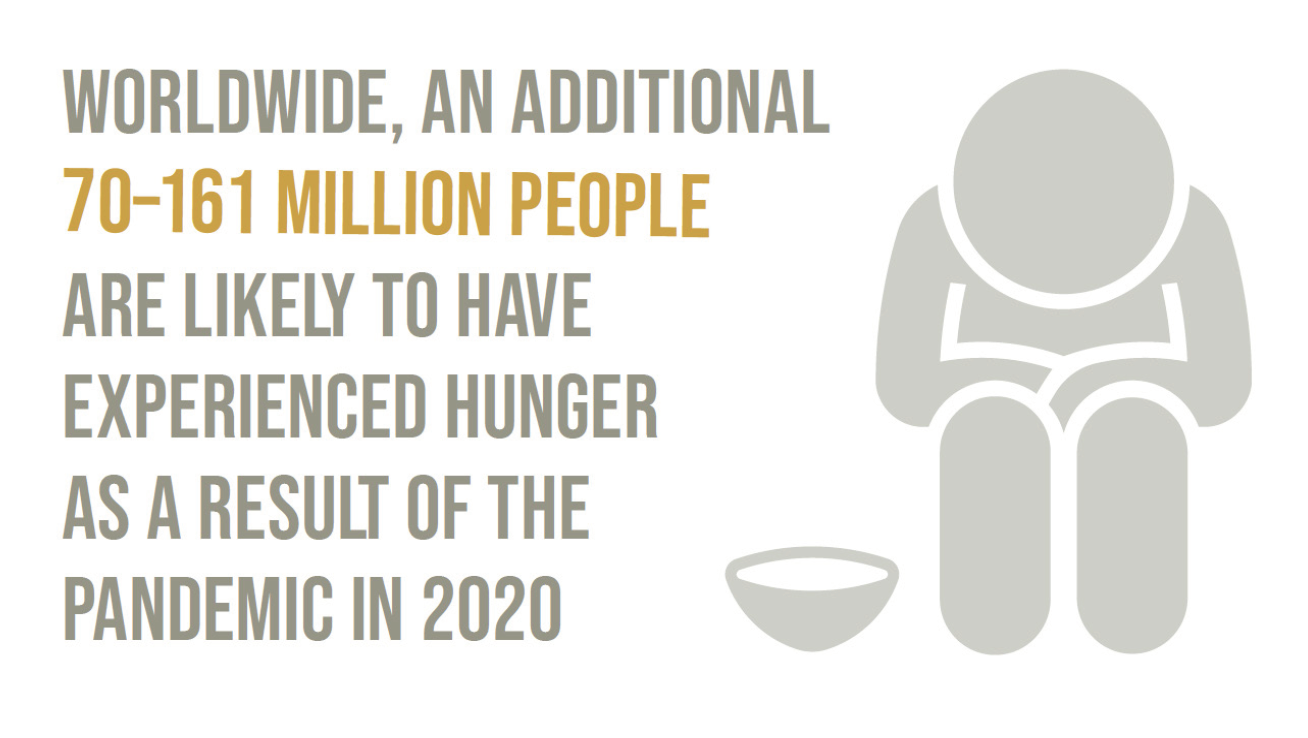

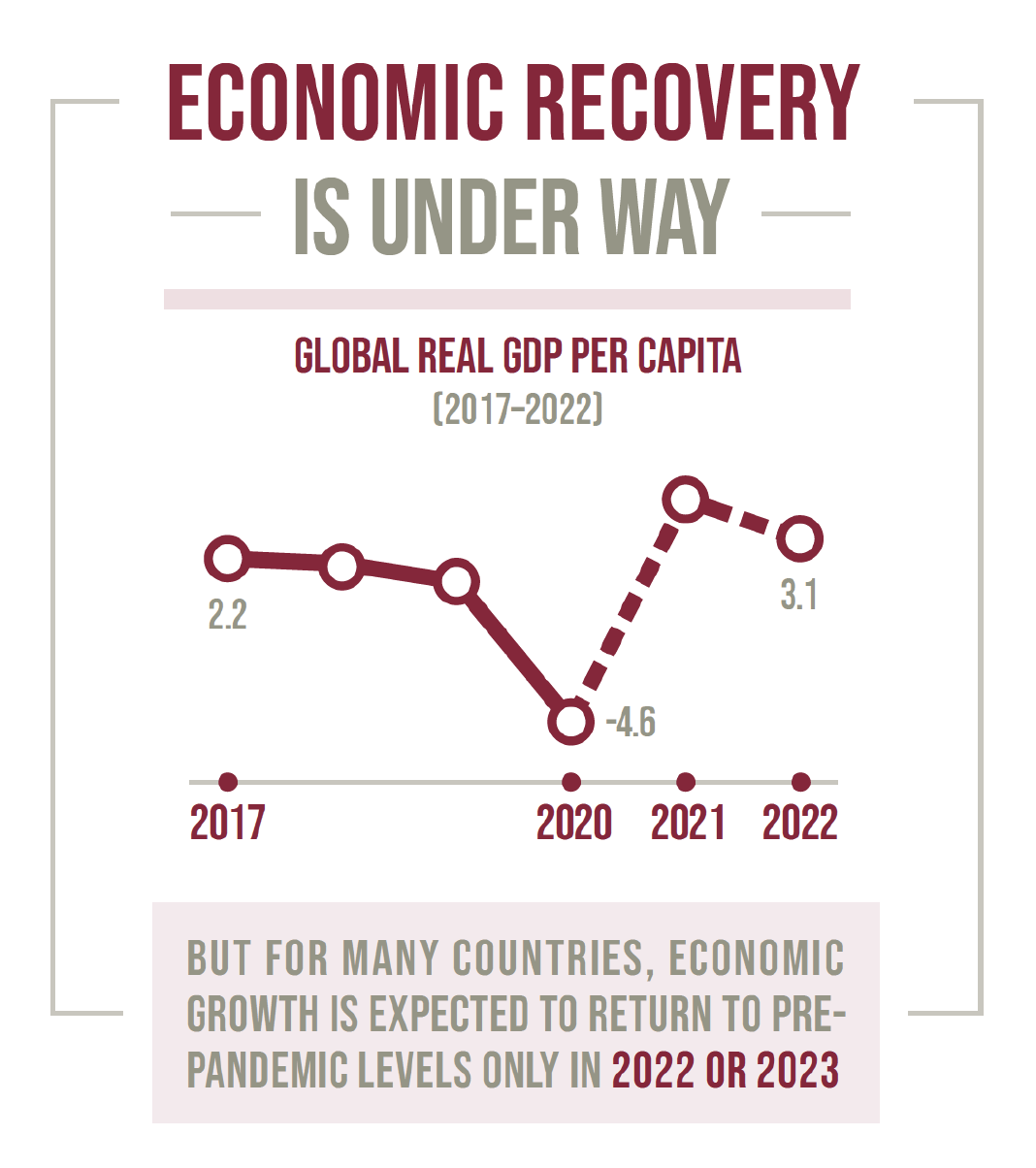

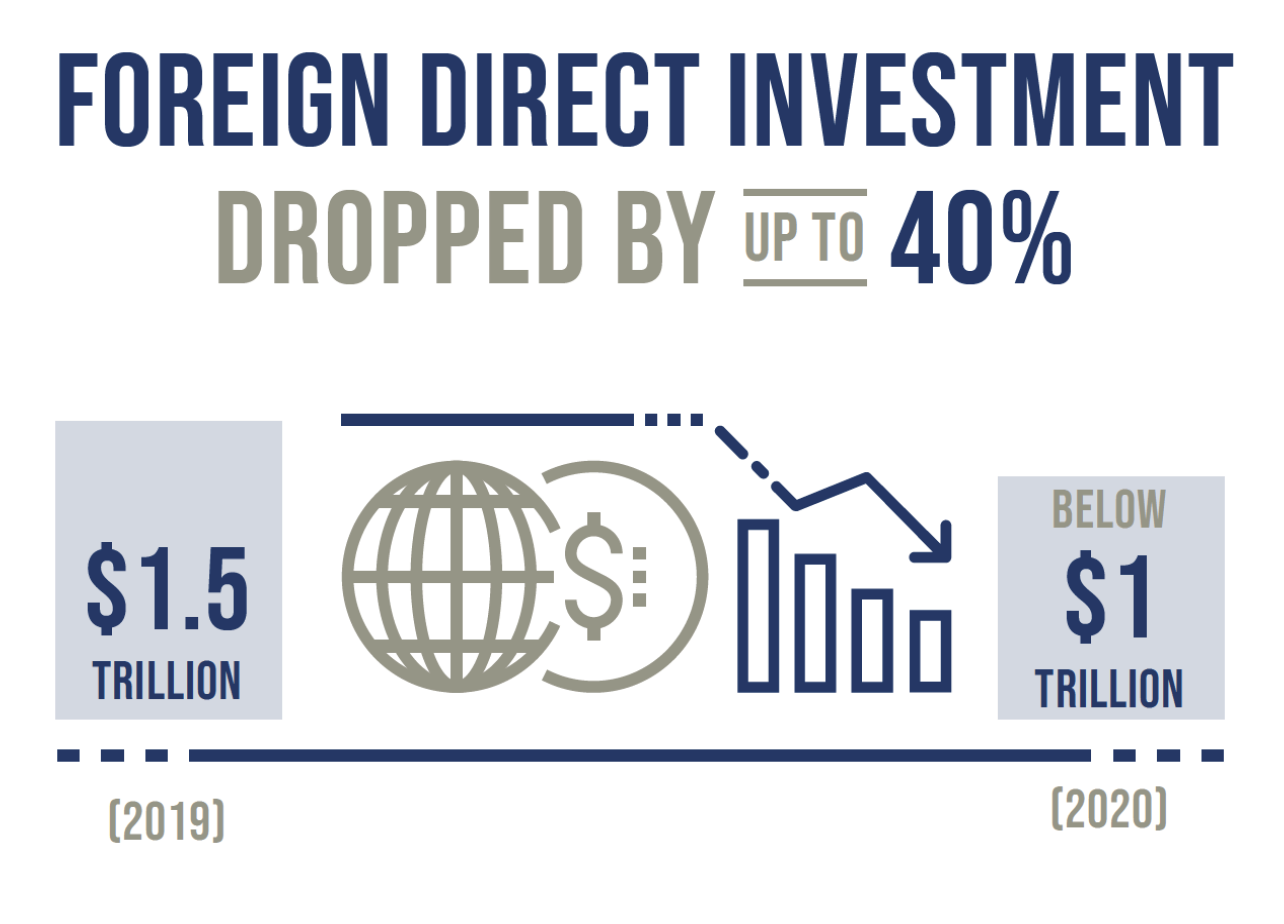

With the roll-out of vaccines and continued fiscal and monetary support, a global economic recovery is under way, albeit with a great divergence appearing between countries. Some, where COVID-19 is sufficiently under control, are returning to growth and health, while others continue to be dragged down by the pandemic. For many countries, economic growth is not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2022 or 2023. The interconnected global economy requires a global response to ensure that all countries, developing countries in particular, can address compounding and parallel health, economic and environmental crises and recover better.  In 2020, foreign direct investment dropped by close to 40 per cent compared to 2019. Although official development assistance in 2020 increased to a historical high of $161 billion, it still fell well short of the target of 0.7 per cent of donors’ gross national income. The pandemic is further testing multilateral and global partnerships that were already shaky due to scarce financial resources, trade tensions, technological obstacles and a lack of data. The impacts of the pandemic are leading to debt distress in many countries, and also limiting countries’ fiscal and policy space for critical investments in recovery (including access to vaccines), climate action and the SDGs, threatening to prolong recovery periods. Despite a surge in data demand to inform pandemic-related policymaking, development support to data and statistics has not risen much. Sixty-three per cent of low-income and lower-middle-income countries need additional financing for data and statistics due to the pandemic.

In 2020, foreign direct investment dropped by close to 40 per cent compared to 2019. Although official development assistance in 2020 increased to a historical high of $161 billion, it still fell well short of the target of 0.7 per cent of donors’ gross national income. The pandemic is further testing multilateral and global partnerships that were already shaky due to scarce financial resources, trade tensions, technological obstacles and a lack of data. The impacts of the pandemic are leading to debt distress in many countries, and also limiting countries’ fiscal and policy space for critical investments in recovery (including access to vaccines), climate action and the SDGs, threatening to prolong recovery periods. Despite a surge in data demand to inform pandemic-related policymaking, development support to data and statistics has not risen much. Sixty-three per cent of low-income and lower-middle-income countries need additional financing for data and statistics due to the pandemic.

Resilience, adaptability and innovation bring us optimism

However, in the face of tremendous challenges, many Governments, the private sector, academia and communities have demonstrated quick responses, remarkable creativity and new forms of collaboration. Between 1 February and 31 December 2020, Governments worldwide announced more than 1,600 new social protection measures in response to the crisis, but almost all (95 per cent) were short term in nature.  Many governments have embraced digital technologies to deliver accessible, reliable, and inclusive services, especially for vulnerable groups. The pandemic has sped up the digital transformation of Governments and businesses, profoundly changing the ways in which we interact, learn and work. Scientists across the globe have been working together to develop life-saving vaccines and treatments in record time. There has been a positive trend in the development of national instruments and strategies for the SDGs. For instance, by 2020, 83 countries and the European Union reported a total of 700 policies and implementation activities under the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production. The Race to Zero campaign launched in June 2020 has formed a coalition of businesses, cities, regions and investors around net-zero carbon emission initiatives and set out specific near-term tipping points for more than 20 sectors of the global economy. In addition, almost all countries have adopted legislation for the prevention of invasive alien species.

Many governments have embraced digital technologies to deliver accessible, reliable, and inclusive services, especially for vulnerable groups. The pandemic has sped up the digital transformation of Governments and businesses, profoundly changing the ways in which we interact, learn and work. Scientists across the globe have been working together to develop life-saving vaccines and treatments in record time. There has been a positive trend in the development of national instruments and strategies for the SDGs. For instance, by 2020, 83 countries and the European Union reported a total of 700 policies and implementation activities under the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production. The Race to Zero campaign launched in June 2020 has formed a coalition of businesses, cities, regions and investors around net-zero carbon emission initiatives and set out specific near-term tipping points for more than 20 sectors of the global economy. In addition, almost all countries have adopted legislation for the prevention of invasive alien species.

Investing in data and information infrastructure is critical

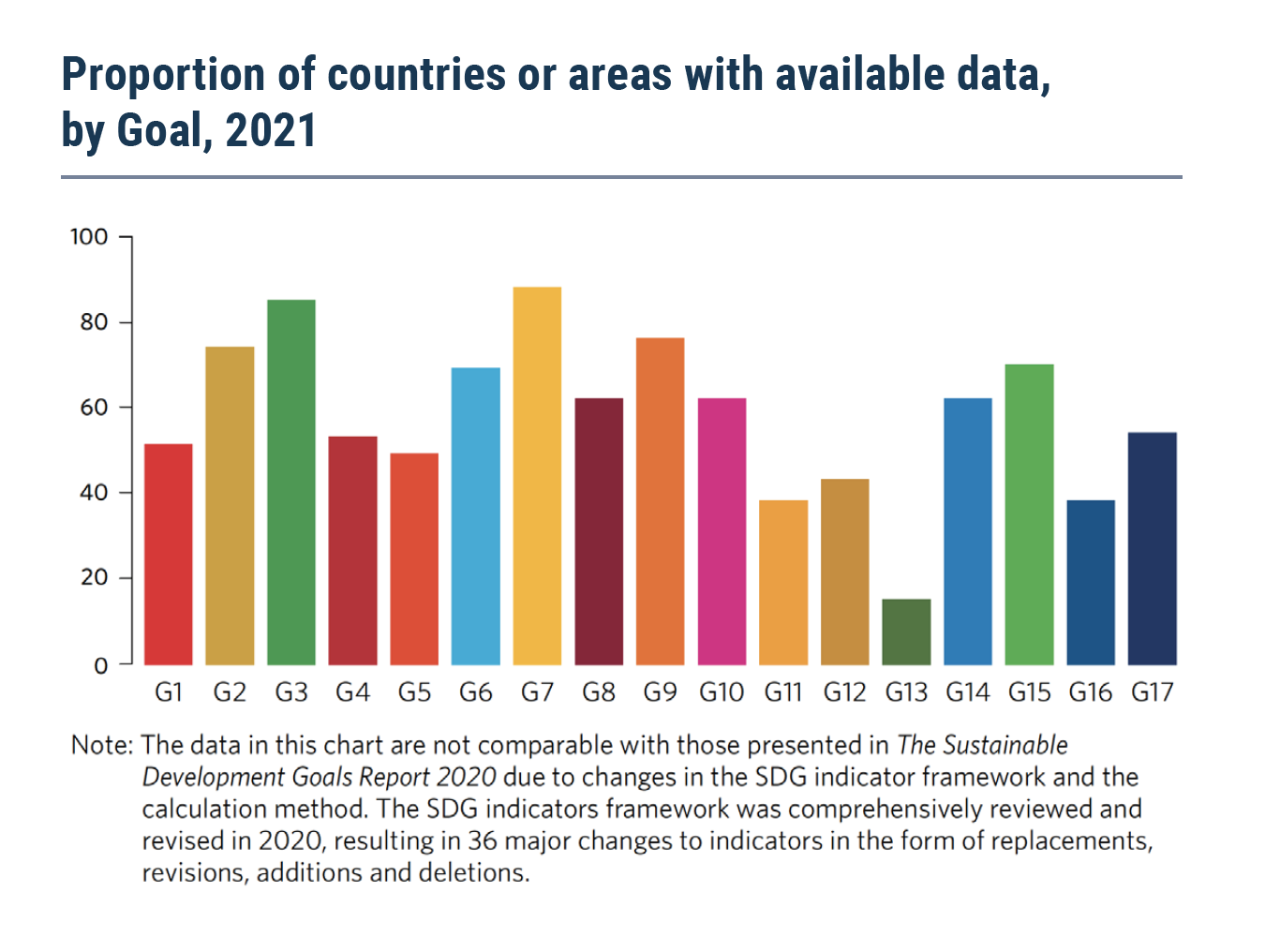

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers and business leaders have routinely had to make time-sensitive decisions, many of which have life-or-death consequences. Yet even basic data to guide decision-making – on health, the society and the economy—are often lacking. For instance, globally, only 62 per cent of countries had a death registration system that was at least 75 per cent complete in 2015–2019; the share in countries in sub-Saharan Africa was less than 20 per cent. While public health surveillance systems have made tremendous efforts in reporting COVID-19 cases to the World Health Organization (WHO), basic characteristics such as age and sex are often missing. A year into the pandemic, only about 60 countries had data on COVID-19 infection and death rates that could be disaggregated by age and sex and that were publicly accessible. The pandemic has brought to the forefront the critical importance of such data and has also accelerated the transformation of data and statistical systems. National statistical offices (NSOs) have forged new collaborations and leveraged alternative data solutions while increasing efforts to protect data privacy and confidentiality to meet the demands of policy—and decision makers. As of September 2020, 82 per cent of NSOs were involved in data collection on COVID-19 and its impacts, some through innovative methods such as online and telephone-based surveys, as well as the use of administrative, credit card and scanner data.  Considerable progress has been made in the availability of internationally comparable data on the SDGs. The number of indicators included in the Global Sustainable Development Goal Indicators Database increased from 115 in 2016 to 166 in 2019 and further to 211 in 2021. However, despite improvements, big data gaps still exist in all areas of the SDGs in terms of geographic coverage, timeliness and the level of disaggregation required. An analysis of the indicators in the Global SDG Indicators Database reveals that, for 5 of the 17 Goals, fewer than half of 193 countries or areas have internationally comparable data. Country-level data deficits are particularly worrisome in Goal 13 (climate action), but also significant in areas related to sustainable cities and communities (Goal 11), peace, justice and strong institutions (Goal 16), sustainable production and consumption (Goal 12), and gender equality (Goal 5). As the pandemic continues to unfold, and the world moves further off track in meeting the 2030 SDG deadline, timely and high-quality data are more essential than ever. Investing in data and information systems is not money wasted. Indeed, data are being widely recognized as strategic assets in building back better and accelerating the implementation of the SDGs. What is needed now are new investments in data and information infrastructure, as well as human capacity to get ahead of the crisis and trigger earlier responses, anticipate future needs and design the urgent actions needed to realize the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Considerable progress has been made in the availability of internationally comparable data on the SDGs. The number of indicators included in the Global Sustainable Development Goal Indicators Database increased from 115 in 2016 to 166 in 2019 and further to 211 in 2021. However, despite improvements, big data gaps still exist in all areas of the SDGs in terms of geographic coverage, timeliness and the level of disaggregation required. An analysis of the indicators in the Global SDG Indicators Database reveals that, for 5 of the 17 Goals, fewer than half of 193 countries or areas have internationally comparable data. Country-level data deficits are particularly worrisome in Goal 13 (climate action), but also significant in areas related to sustainable cities and communities (Goal 11), peace, justice and strong institutions (Goal 16), sustainable production and consumption (Goal 12), and gender equality (Goal 5). As the pandemic continues to unfold, and the world moves further off track in meeting the 2030 SDG deadline, timely and high-quality data are more essential than ever. Investing in data and information systems is not money wasted. Indeed, data are being widely recognized as strategic assets in building back better and accelerating the implementation of the SDGs. What is needed now are new investments in data and information infrastructure, as well as human capacity to get ahead of the crisis and trigger earlier responses, anticipate future needs and design the urgent actions needed to realize the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a wake-up call for transformative changes

To address deeply rooted problems in our societies revealed by the pandemic, Governments and the international community should make structural transformations and develop common solutions guided by the SDGs. The first step requires ensuring equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. Other actions include significantly strengthening social protection systems and public services, including health systems, education, water, sanitation and other basic services) and increasing investments in the care economy, to ensure no one is left behind. Additionally, increasing investment in data and in science, technology and innovation is crucial as well as creating fiscal space in developing countries to address debt distress, taking a green-economy approach and investing in clean energy and industry. Last but not least, we need a unified vision of coherent, coordinated and comprehensive responses from the multilateral system. The year 2021 will be decisive as to whether or not the world can make the changes needed to deliver on the promise to achieve the SDGs by 2030 – with implications for us all. It is crucial that we seize the moment to make this a decade of action, transformation and restoration to achieve the SDGs.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations