BACKGROUND

Amid uneven SDG progress and overlapping crises, efforts to deliver sustainable development that leaves no one behind continue to face persistent, intersecting barriers—even where commitments are strong. Consider, for example, the experience of a woman with a disability in an informal settlement: she cannot afford assistive devices, faces inaccessible infrastructure, encounters weak enforcement of rules, experiences hiring bias and may struggle to evacuate during an earthquake. This scenario shows how multiple barriers converge to deepen exclusion.

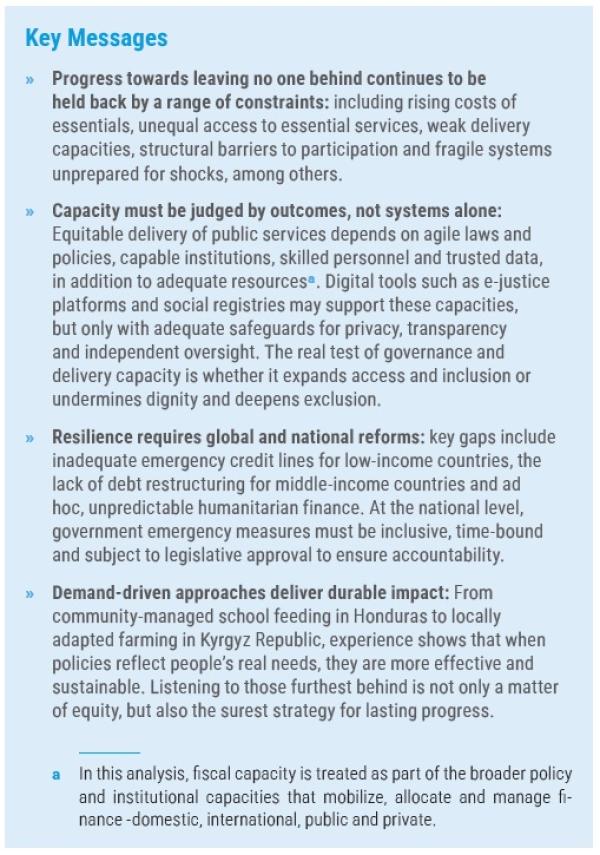

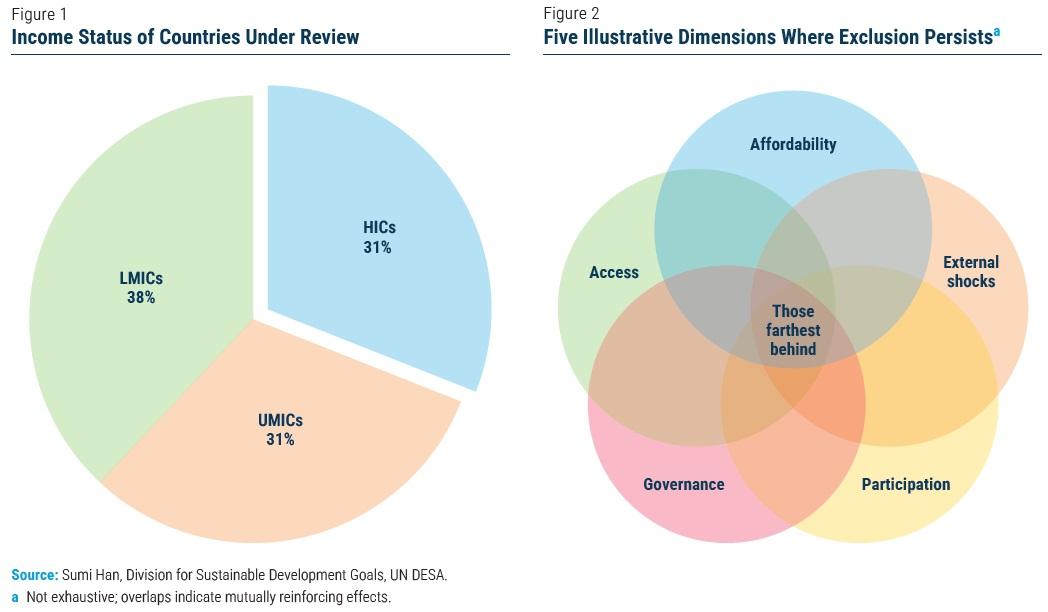

This policy brief highlights five dimensions where exclusion is often observed—affordability, access, governance, participation and external shocks, among others—and illustrates how governments are responding in each through policy examples and observations. Insights are drawn from 2024–2025 country implementation updates from thirteen countries that announced commitments at the 2023 SDG Summit, as well as 2025 Voluntary National Review (VNR) reports from three additional countries3 with such commitments. The analysis is intended to inform global policy discussions, including, as relevant, the World Social Summit under the title Second World Summit for Social Development.

The countries under review span high-, upper-middle- and lower-middle-income contexts (Figure 1). To provide clarity on both the structure and the country samples, the brief organises the policy observations under five dimensions (Figure 2).

1. Affordability: High costs are pricing people out of essentials

The World Economic Situation and Prospects 2025 notes that global inflation is easing, yet at different rates in developed and developing economies; real wages in some countries remain below 2019 levels and food inflation still persists in many developing contexts. The resulting cost-of-living crisis has eroded household purchasing power world-wide, with rising prices for essentials such as energy and food hitting lower-income groups, rural communities and older persons hardest, deepening “inflation inequality.” Compounding this, the global housing affordability crisis now affects 3 billion people.

Governments are responding with a mix of social protection, sector-specific and labour-market measures to protect incomes, keep essentials affordable and build resilience.

Social protection coverage is being expanded by countries through different measures, such as a unified registry and cash transfers (Lesotho), targeted education vouchers (Kyrgyz Republic) and inflation-indexed benefits (Ghana, see Box 1). Sectoral measures include subsidized health coverage for nearly 870,000 poor households (Benin); reforms cutting catastrophic out-of-pocket medical costs (Thailand); a multi-stakeholder school meals programme for 1.3 million children that sources over 90% of food from local smallholder farmers supporting local economies (Honduras); and energy subsidies to ease utility bills (Moldova). Labour market measures—from higher minimum wages and pensions (Azerbaijan) to public works schemes (Lesotho)—also aim to shield workers from volatility.

What this means: Cushioning measures can help ease cost pressures, but their effectiveness depends on being carefully tailored to the needs of vulnerable groups. Broader proposals for universal coverage, such as Universal Basic Income (UBI), are resurfacing in global debates, raising both hopes and concerns (see Box 2).

2. Access: Unequal access to basic services persists

Exclusion often begins at the frontline service delivery—when schools, clinics and other facilities are out of reach or not accessible. The World Social Report 2025 stresses that universal access to education, healthcare and other basic services is vital to breaking inequality, yet quality often falls short. For instance, without universal design, which makes facilities and systems accessible to all, including persons with disabilities, expanded infrastructure risks bypassing large segments of the population.

Evidence shows that these gaps remain stark. According to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025, in least developed countries (LDCs), over half of primary schools lack electricity; over a third lack basic sanitation; two-thirds have no digital tools; and only one in five offer disability-friendly facilities. Additionally, 84% of people without electricity in 2023 lived in rural areas glob-ally, reflecting entrenched geographic inequalities in infra-structure investment.

Against this backdrop, governments are responding with targeted in-vestments to enhance the reach and quality of essential services.

In education, access is widening through distance and family-based learning, with targeted support for low-income children and those with disabilities or medical needs, alongside expanded early-intervention services (Kyrgyz Republic). Resource centres and one-stop hubs now reach more youth, including those with disabilities (Botswana). The UK contributed £180 million to the International Finance Facility for Education (IFFEd) for marginalised children, including girls, the poor and those facing rural–urban disparities. In healthcare, services are extending to hard-to-reach localities and vulnerable groups through mobile care teams (Moldova, see Box 3). Also, safe drinking water is being provided through community-managed desalination plants (Bangladesh); and an emergency trans-port system has been set up for expectant mothers in rural areas (Lesotho, see Box 3).

What this means: Governments should use demand-driven approaches to close access gaps: identify those furthest behind, remove barriers (e.g., cost, transport), design and deliver services locally and monitor delivery for accountability. Recent analyses suggest high returns to investing in those furthest behind: further context-specific evidence should be accumulated.

3. Governance: Weak capacities undermine equitable delivery of public services

Exclusion persists when governance is weakened by gaps in laws, policies, institutions, human resources and data management. Ultimately, governance shapes whether and how people benefit equitably from what governments pro-vide and regulate.

To address these systemic gaps, countries are reinforcing core governance and delivery capacities so that services reach intended beneficiaries equitably and predictably.

- Legal capacity is enhanced through uniform frameworks such as mandatory Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (Greece); and through justice system reforms (Bangladesh, see Box 4), which fall under broader e-justice measures highlighted in the World Public Sector Report 2023.

- Policy capacity is advancing through embedding the principle of leaving no one behind in long-term development strategies (Thailand); and institutionalizing predictable ODA policy (Denmark, see Box 5).

- Institutional capacity is strengthened through consistent, nationwide application of social assistance laws via Territorial Social Assistance Agencies (Moldova) and by a national SDG forum that includes vulnerable groups in decision-making (Lesotho).

- Human resources capacity is expanding through work-force growth, targeted training and improved remuneration for frontline workers. Recruitment now requires gender- and age-sensitive skills; police officers must hold social work or psychology qualifications (Botswana).

- Data and digital capacity are scaling, with cross-sectoral data platforms (Moldova); data integration (Thailand, see Box 6); and upgraded digital social registries for coordinated social assistance (Benin).

What this means: Equitable delivery rests on capacities for coherent laws and policies, capable institutions, skilled personnel and trusted data, all underpinned by robust accountability mechanisms. Digital tools—such as data integration, e-justice platforms and social registries—may support these capacities only with safeguards against bias and misuse and for privacy, transparency and independent oversight. The test is whether capacity expands access and inclusion or under-mines dignity and deepens exclusion.

4. Participation: Structural constraints restrict equal opportunities

Barriers to equal participation often stem less from missing infrastructure or services, but more from the ways rules, incentives and institutional processes are structured and experienced unequally across society. To tackle these challenges, governments18 are embedding equity into national frameworks and systems, for example through justice reforms with child-friendly courts, ombudsman mechanisms and specialised policing procedures (Botswana); wide-ranging legal and institutional reforms towards gender equality (Azerbaijan); Roma integration strategies that expand opportunities in education, employment and housing while recognising anti-gypsyism as a barrier to social cohesion (Czech Republic); and gender-responsive budgeting (Lesotho).

What this means: Overcoming exclusion requires strategic reforms that address structural exclusions and biases, realign incentives and translate commitments into practice, ensuring that all people can participate on an equal footing.

5. External Shocks: Fragile systems fuel exclusion

External shocks, from economic downturns to disasters and conflicts, are vulnerability multipliers. They com-pound existing gaps in affordability, access, governance and participation, and strain systems faster than they can adapt. These also come against a backdrop of rising debt burdens that squeeze social spending and global safety nets that fall short. Without resilient systems, shocks risk pushing vulnerable populations deeper into poverty and exclusion.

To counter these pressures, governments are strengthening shock-responsive systems to help households withstand crises and recover more equitably.

In Ghana, the integrated national financing framework (INFF) and SDG Investor Maps are being employed as country-owned risk-management tools to diversify financing under debt pressures, support inclusive budgeting and harness remittances as a buffer against shocks. At the global level, €5 billion were invested in global food security to cushion war impacts and promote long-term resilience (Germany).

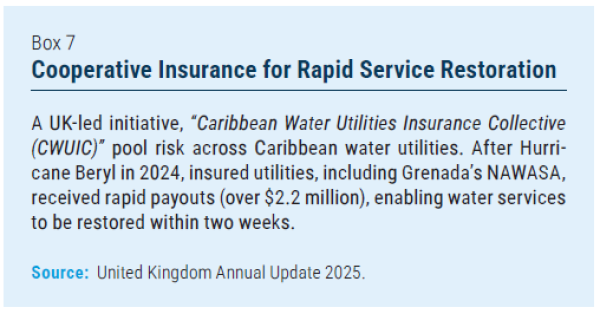

In preparation for natural disasters, cooperative insurance schemes are helping utilities recover quickly (United Kingdom, see Box 7); waste management is being modernized through regional recycling complexes to strengthen urban resilience (Belarus); and dataset systems are advancing environmental monitoring and early warning (Czech Republic).

In the Sahel, where drought and fragility exacerbate vulnerabilities, adaptive social protection measures bridge humanitarian relief and long-term poverty strategies, reaching displaced populations (Germany’s cooperation). In conflict contexts, integration strategies support the inclusion of refugees in host communities (Czech Republic, see Box 8).

What this means: Resilient financial systems and emergency services, supported by effective development cooperation, are key to softening the impacts of external shocks. Urgent reforms are needed, among others, in expanding emergency credit lines for low-income countries; extending debt restructuring frameworks to middle-income countries; and securing predictable humanitarian finance. Such measures also help to address structural inequities in the international financial system that perpetuate poverty and inequality. At the national level, emergency measures should be inclusive, strictly time-bound and ex-tended only with legislative approval to safeguard accountability.

Demand-driven pathways to leaving no one behind

This stock take shows that gaps in affordability, access, governance, participation and resilience must be tack-led together to ensure no one is left behind. Across con-texts, a common thread is the imperative of demand-driven solutions—from Ghana’s inflation-indexation system that directly shields the people living in poverty from cost-of-living shocks, to Honduras’ community-driven school feeding programmes anchored in local procurement, Bangladesh’s locally managed desalination systems that secure safe drinking water, and Lesotho’s transport service designed for expectant mothers in rural areas to reach care. When policies are grounded in real needs, they are more likely to last. Listening to those furthest behind is not only a matter of equity, but also the surest strategy for lasting progress.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations