INTRODUCTION

Population ageing is a global phenomenon, a shift towards an increasing share of older persons in the population. Even the least developed countries (LDCs) are beginning to experience the progressive ageing of their populations, and this process is expected to accelerate during the second half of the current century (United Nations, 2023a). Despite its far-reaching consequences, the emergence of this trend in LDCs has attracted only limited attention from both national policymakers and the international community. Most LDCs are still early in the decades-long process of population ageing, which is a direct consequence of the demographic transition towards longer lives and smaller families. Population ageing begins with a slowdown in the growth of the younger population but eventually involves the rapid growth of the older population. Early in this process, countries have an opportunity to benefit from the demographic dividend – a faster rate of economic growth on a per capita basis due to an increasing share of the working age population (and thus a falling dependency ratio) caused by a sustained decline in the fertility level. Although temporary, this opportunity often lasts for several decades. It comes to an end once the older population begins to grow more rapidly, leading to a rising old-age dependency ratio. Preparing for population ageing in LDCs will be critical for achieving sustainable development and ensuring that no one is left behind. Maximizing the benefits from the demographic dividend will provide an opportunity for these countries to develop economically before their populations become much older. It is also consistent with a pledge of “working together to support the acceleration of the demographic transition, where relevant”, as agreed in the Doha Programme of Action for the Least Developed Countries for the Decade 2022–2031 (United Nations, 2022).

LEVELS AND TRENDS OF POPULATION AGEING IN LDCS

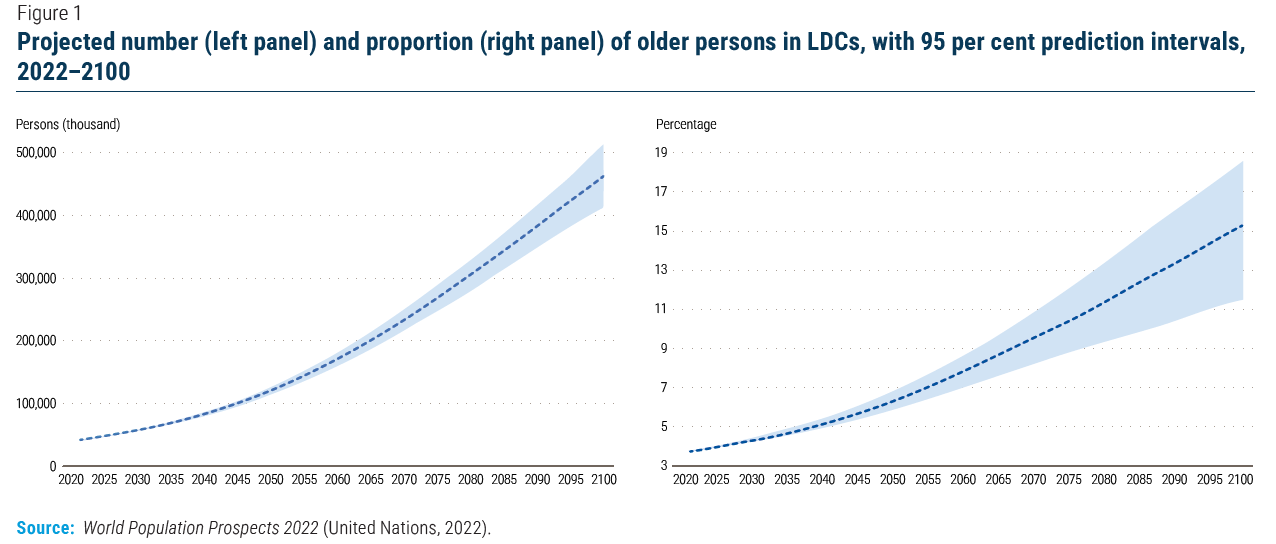

In 2023, the share of persons aged 65 years or over in LDCs was just under 4 per cent, significantly lower than the level of 20 per cent in developed countries and of nearly 9 per cent in other developing countries. This small percentage overall, however, masks large disparities among LDCs1 within and between regions. Moreover, it provides no information about the large numbers of older persons living in these countries. Asia-Pacific LDCs, such as Bangladesh, Cambodia and Myanmar, have higher shares of older persons than LDCs in sub-Saharan Africa. Ten LDCs have over a million persons aged 65 years or older, of which five have surpassed two million and one, Bangladesh, has over 10 million. The proportion of older persons in LDCs is projected to increase from under 4 to around 6 per cent between now and 2050, while the number of older persons in this group of countries is projected to experience a nearly three-fold increase over the same period, rising from about 43 million to 119 million. By 2050, six LDCs are expected to have an older population that exceeds 10 per cent of the total, and 27 LDCs will each have more than one million older persons (United Nations, 2022). Population ageing in LDCs is projected to accelerate in the second half of the current century (figure 1). In African LDCs, the number of older persons is expected to increase more than five-fold, rising from 64 to 340 million between 2050 and 2100. In Asia-Pacific LDCs over the same period, this number is projected to more than double from 55 to 122 million. From mid-century until 2100, African LDCs are expected to see a more than three-fold increase in the share of older persons, which may rise from 4 to 14 per cent, while Asia-Pacific LDCs may witness a more than two-fold increase, rising from 12 to 25 per cent.

WHAT IS THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND AND WHY DOES IT MATTER?

Population ageing is an inevitable consequence of the demographic transition – the historic shift from high to low rates of mortality and fertility – which has occurred or is occurring in all countries and regions. As countries move through the stages of the demographic transition,2 albeit at different times and with varying speeds, their age structures change. A drop in the fertility level results in smaller cohorts at younger ages and raises the share of the working- age population, creating a window of opportunity for accelerated economic growth known as the demographic dividend (Bloom, Canning and Sevilla, 2003; Lee and Mason, 2006). The demographic dividend period normally starts towards the end of the early-transition stage at the onset of the fertility decline.3 However, the economic benefits of the demographic dividend are likely to be greater once countries move into the mid-transition stage, which is often characterized by an accelerated pace of fertility decline (United Nations, 2023a).

In addition to a faster increase in per capita income, the demographic dividend is often accompanied by various behavioural changes, including increased human capital formation, more widespread female labour force participation and rising levels of saving and investment. With fewer children per working adult, both families and governments can increase per capita investments in health and education, while women with fewer childbearing and child-rearing responsibilities can increase their participation in the formal labour force. Supportive policies for education and health care, gender equality, job creation, economic reform and good governance can help to maximize the potential impact of the demographic dividend.

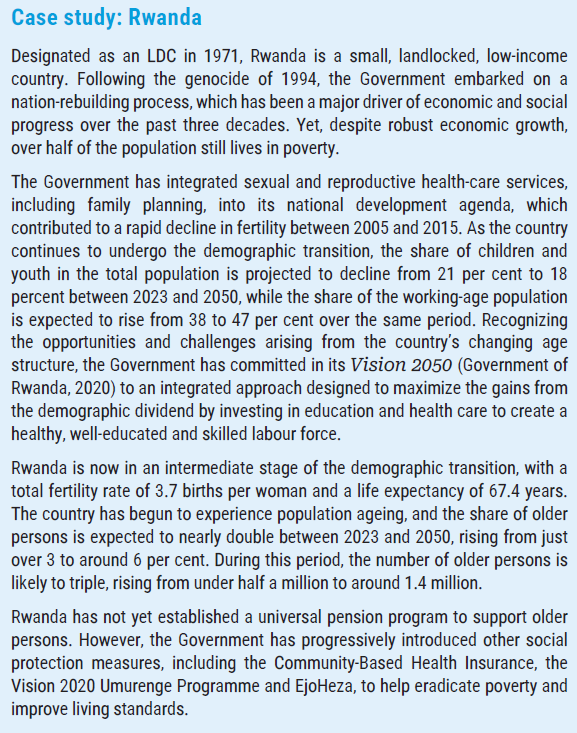

The experiences of the Republic of Korea and of Taiwan Province of China, are often cited as success stories in harnessing the demographic dividend (Mason, 2001). On the other hand, for some countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, countervailing forces have diminished the dividend’s impact (Bloom and Canning, 2008). The Doha Programme of Action encourages LDCs to take advantage of the demographic dividend as part of a strategy to increase the number of countries that will graduate out of LDC status during the decade 2022–2031 (see the box on the case of Rwanda, which has adopted a national strategy for harnessing the demographic dividend).

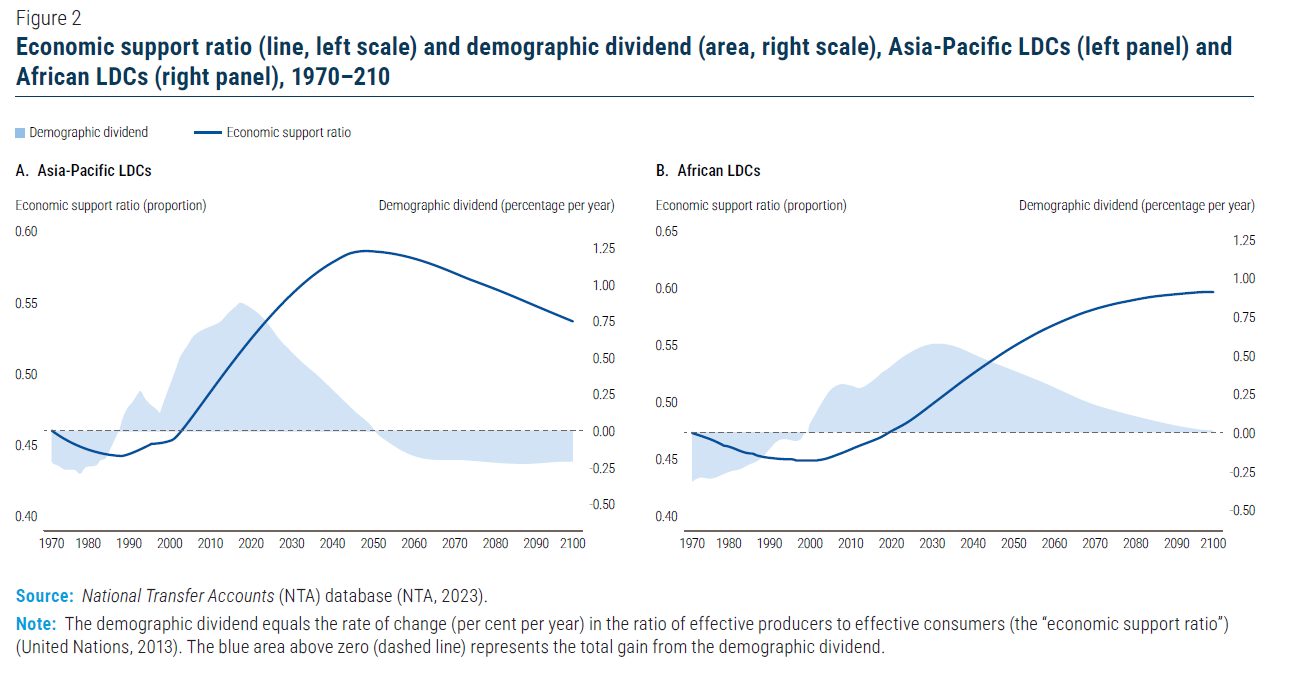

It is estimated that the period of the demographic dividend for the group of Asia-Pacific LDCs started in the late 1980s; it is expected to end around 2050 (figure 2) (National Transfer Accounts, 2023). For LDCs in Africa, where the demographic transition started later and is proceeding more slowly, the dividend period is projected to cover the current century in its entirety, starting around 2000 and extending until around 2100.

The demographic dividend of African LDCs as a group is projected both to last longer and to be less intense than what is being experienced by Asia-Pacific LDCs. The magnitude of the dividend reached a maximum of around 0.9 per cent in the late 2010s for Asia-Pacific LDCs, significantly higher than what is expected for African LDCs, where the dividend is expected to boost the annual growth rate of GDP per capita by up to 0.6 percentage points in the early 2030s.

MAJOR DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES IN HARNESSING THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN LDCS

Persistently high fertility and rapid population growth will remain major challenges facing most LDCs in the coming decades. In 2023, about half of the LDCs had a total fertility rate (TFR) above four live births per woman, and a substantial number of African LDCs are projected to have a TFR of more than three births per woman in 2050. Relatively high levels of fertility combined with improving survival in LDCs translate into continuing rapid population growth, and thus the LDC share of the global population is projected to double from 10 to 20 per cent between 2023 and 2050. High levels of fertility are often linked to a lack of autonomy and opportunity among women and girls (United Nations, 2021).

More schools and teachers will be needed in LDCs for children in primary (ages 6–11 years) and secondary (ages 12–17 years) education, given that the populations of these age groups are projected to increase from 171 and 153 million in 2023 to 235 and 223 million in 2050, respectively. African LDCs are likely to see continuously expanding school-age populations well beyond mid-century.

With rising shares of the working-age population in most LDCs, policies are needed to support productive employment and decent work for all. In addition, governments should promote technical and vocational education and training, as well as upskilling and reskilling of the existing work force, to reinforce the economic gains from the demographic dividend (United Nations, 2023b).

Despite significant progress in development, LDCs still suffer from high levels of poverty and inequality, low levels of education, weak health-care systems and insufficiently diversified economies. They are highly dependent on official development assistance (ODA), and their public spending on education, social protection and health care is generally insufficient to meet the needs of their populations.

Constrained domestic budgets and high levels of foreign debt limit the fiscal space available to LDCs to promote quality education and ensure access to health care and decent work. Their prospects for prosperity are limited further by global crises including the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and other violent conflicts, as well as the ripple effects of global geo-political tensions. They are also highly susceptible to the negative impacts of climate change on agriculture and food production.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Governments of LDCs should strengthen efforts to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health care, including for family planning, in combination with measures to protect reproductive rights and empower all women and girls. Such actions will help women and their partners to realize their reproductive preferences. For countries in the early stages of the demographic transition, increased access to family planning will likely contribute to fertility decline, leading to slower population growth, a more rapid move towards population stabilization, and a more intensive and concentrated demographic dividend.

Governments should proactively expand and improve their programmes providing social protection and health-care services, as appropriate, to address the needs of present and future cohorts of older persons, in particular those employed in the informal sector without access to public pensions, health care and other forms of social protection.

Governments with rapidly growing school-age and working-age populations should prioritize investments to promote human capital formation, including by skills upgrading for the working age population, accelerating the diversification of economic production while promoting productive employment and decent work for all.

Building strong governance frameworks will allow countries to mobilize domestic private and public resources more effectively, attract long-term foreign investment and reduce dependency on external funding sources, including ODA and loans. Guided by the Doha Programme of Action, the international community should continue to support LDCs by providing development assistance and technical cooperation, including for tackling the prohibitive costs of servicing their debt and reducing the risks of debt distress.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations