In the three decades that preceded the Covid-19 pandemic, more than one billion people escaped extreme income poverty. As the health and economic upheavals brought on by Covid-19 and subsequent crises have made evident, however, progress towards poverty eradication is fragile.

With only a few years remaining before the target date of 2030 for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), there is a renewed commitment to accelerate progress towards poverty eradication. In 2025, the United Nations will convene the Second World Summit for Social Development to give momentum towards the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, with a focus on poverty eradication and the other two pillars of social development. The Summit should strengthen the international community’s resolve to end poverty everywhere between now and 2030.

Helping people escape extreme poverty is the first step towards achieving SDG 1. However, growing evidence on the poverty trajectories of families shows that escapes from poverty are seldom a straightforward path. Many people lift themselves out of poverty but fall back into it when a shock hits. A sharper policy focus on preventing impoverishment is needed to sustain progress and avoid setbacks.

MOVING IN AND OUT OF POVERTY – COMPLEX DYNAMICS

Poverty is a widespread risk. Many more households are affected by poverty than those observed to be living in poverty at specific points in time. In recent decades, the growing availability of longitudinal data – from surveys that follow the same people over time – has shown that household income and consumption fluctuate significantly. Some people who move out of poverty escape it permanently, while others do so only temporarily. Some people are born into poverty and remain trapped there for long periods and even across generations, while others avoid the experience of poverty altogether. Even though the number of people living in poverty may be stable or decline slowly, the composition of this population is in constant flux. As a result, progress in reducing poverty is much more volatile than suggested by the conventional picture of gradual reductions overall.

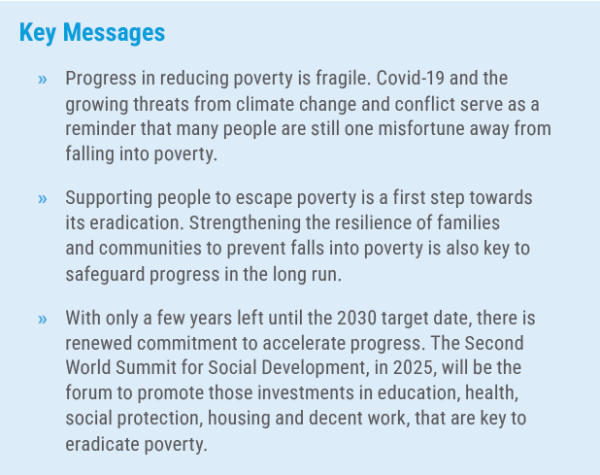

Although the necessary data are still lacking in many low and middle-income countries, researchers have been able to quantify flows into and out of poverty for some populations. For low- and middle-income countries with available data, or for areas within such countries, figure 1 categorizes people who experienced extreme poverty according to whether they made sustained or transitory escapes from poverty, became poor or were chronically poor during the time periods shown.

Sustained escapes were the most common trajectory in rural areas of Bangladesh (2011-2019) and Cambodia (2008-2017) and in Nepal (1995/96-2010/11). Bangladesh and Cambodia experienced consistent economic growth with employment creation and significant wage growth during the observation periods, with a move away from jobs in agriculture towards employment in greater value-added activities, including in rural areas. In contrast, Nepal’s sustained escapes from poverty took place amidst low rates of employment and economic growth. The country’s brisk poverty reduction is explained mainly by the end of internal armed conflict in 2006 and by the high and stable flow of remittances.

Negative trajectories or temporary escapes prevailed in most other countries, suggesting that many people lack the resilience to withstand life course shocks – for example, ill health, job loss, crop failure – let alone systemic regional, national or global crises. In some cases, the share of people who lived in extreme poverty throughout the observation period was substantial. For example, in Ethiopia (2011/12-2015/16) and in rural Zambia (2012-2019), more than 60 per cent of those who experienced extreme poverty were chronically poor.

These examples make it plain that reaching the elusive goal of eradicating poverty requires more than merely helping people to move out of poverty. It also requires building the resilience that can protect people against major risks. Many households rise above the poverty line only to fall back beneath the threshold, highlighting the precarious nature of many escapes from poverty. A dynamic perspective also reveals that many more people are affected by poverty than those observed to be experiencing it at specific moments. Thus, poverty should be seen as a widespread risk rather than as a condition that affects a limited or fixed group of individuals.

ABOVE EXTREME POVERTY, BUT STRUGGLING TO STAY AFLOAT

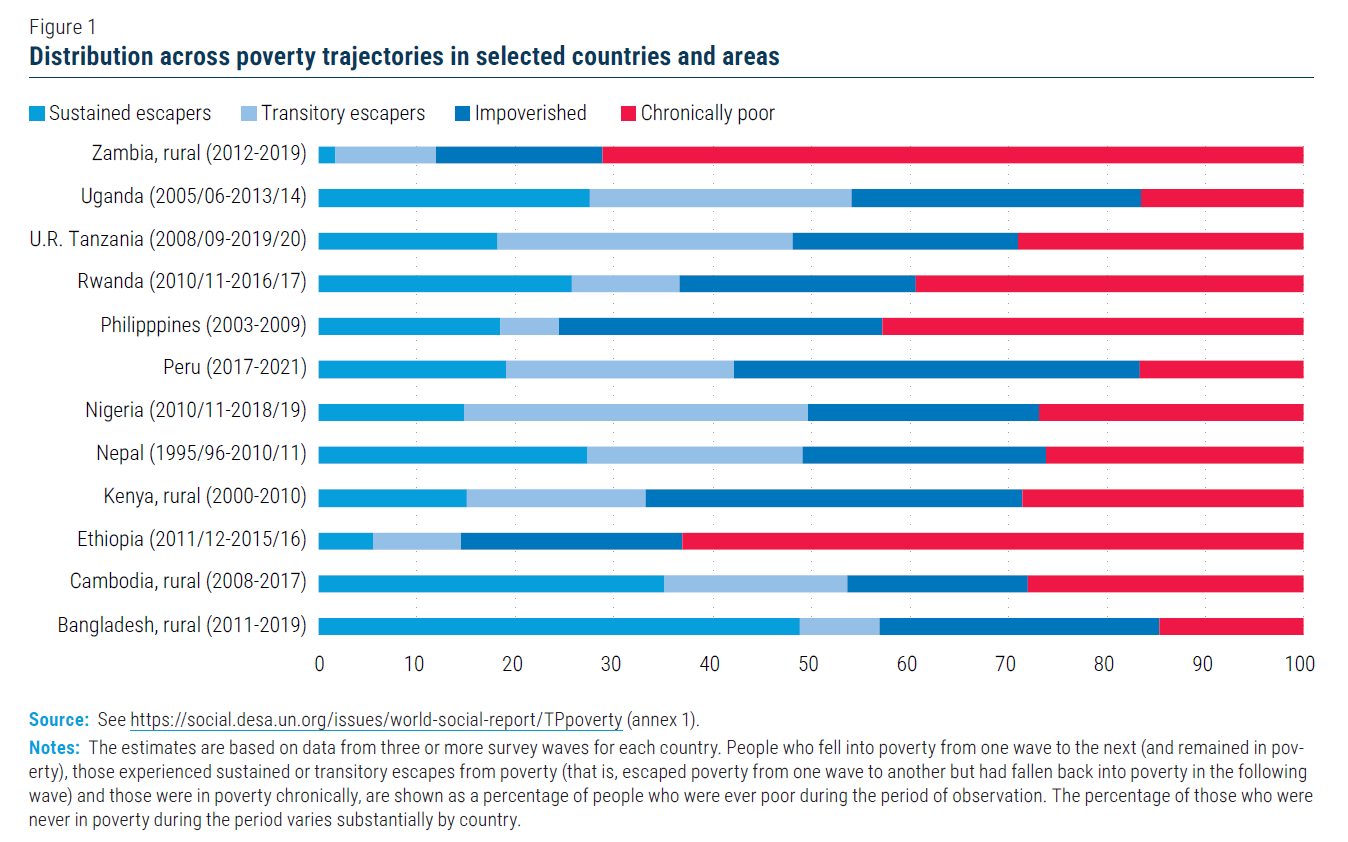

The urgency of taking action to prevent falls into poverty cannot be overstated. In 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic, almost 1.2 billion people, or 15 per cent of the world’s population, lived between the extreme poverty line of $2.15 a day and the threshold of $3.65 a day that is typical of national poverty lines used in lower-middle-income countries (figure 2). Even more people, close to 1.8 billion, lived between $3.65 and $6.85 a day. In all, almost half of the world’s population, including large majorities in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, have levels of economic well-being that fall below the national poverty line of some upper-middle income countries. Even a minor health problem, an increase in transportation fares or a below-average crop yield could push them into extreme poverty.

Economic insecurity does not end above the threshold of $6.85 a day. Many people teeter on the brink of poverty even as they move up the income ladder. Research in developing regions has shown that individuals and families wedged between poverty and the middle class struggle to stay out of poverty, with health shocks standing out as a primary driver of impoverishment in this group. Many of these “strugglers” work in informal employment, where social protection programmes are largely absent. They have limited or no access to unemployment benefits, public health insurance or public pension programmes after retirement. In many countries, the near-poor pay more in taxes than they receive in public transfers. Many of them run businesses and generate jobs on which persons living in poverty may rely, and thus their fortunes are closely linked with those of many people living in poverty.

AN UNCERTAIN CONTEXT FOR POVERTY REDUCTION GOING FORWARD

Recent crises and growing threats from climate change and conflict have exposed massive vulnerabilities, making the universal need to strengthen resilience even more pressing. The largest and most persistent impacts are often felt far from where a crisis originated. The much slower recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic and overlapping crises experienced by low-income countries has amplified global disparities in the prevalence and incidence of poverty.

About 2.3 billion people out of the 4.5 billion exposed to extreme weather events in 2019 were living in poverty. While people in poverty are more exposed to droughts, floods and other environmental shocks, exposure to such events increases the likelihood of living in chronic poverty. A one-degree Celsius increase in temperature has been associated with a 1.6 percentage-point increase in the prevalence of chronic poverty below the threshold of $3.65 a day.

The nexus between conflict and poverty is particularly overwhelming. Globally, the estimated share of people living in extreme income poverty who reside in fragile and conflict-affected countries increased from about 20 per cent in 2000 to 48 per cent in 2019, even though these countries accounted for only 10 per cent of the world’s population in 2019. If such trends continue, two-thirds of people living in extreme poverty worldwide will be living in fragile and conflict-affected countries in 2030.

A GREATER POLICY FOCUS ON PREVENTING IMPOVERISHMENT

Growing evidence on household income dynamics and what drives falls into and escapes from poverty should inform the economic, social and environmental transformations and policies needed to support poverty eradication and avoid setbacks. However, policy design and implementation have not kept up with the evidence. While many countries have strengthened the policy and institutional frameworks that help people escape poverty, preventing impoverishment and tackling chronic poverty remain outstanding challenges.

Escapes from poverty have usually exceeded falls into poverty during periods of rapid economic growth, when such growth has been employment-rich and real wages have risen. However, countries have often missed the opportunities created by periods of expansion to take on the massive investments in social protection, education, health care and infrastructure that can help people to manage risk and stay out of poverty in the long run. Similarly, relief efforts during and after major crises, as well as peacebuilding efforts in countries emerging from conflict, have often prioritized actions for short-term recovery while neglecting the long-term investment and institutional capacity-building that would support sustained escapes from poverty.

The value of social protection systems to shield individuals and families from shocks and to prevent falls into poverty has been broadly recognized. Yet, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, less than 15 per cent of the population of sub-Saharan Africa and under 25 per cent of the population of Southern Asia were covered by at least one social protection benefit. Today, the institutional capacity and fiscal space of countries in these regions to respond to this and other crises continue to be limited. Considering that health shocks are a primary cause of impoverishment, health care coverage is crucial. Even though coverage has

increased quickly in recent decades, benefits are still inadequate in most developing countries. Out-of-pocket health spending represents over one-third of total health expenditures in 65 out of 186 countries and areas with data and, in some cases, is as high as 80 per cent.14 While private health insurance plans can complement public support, publicly funded social protection remains necessary for most of the world’s population, and its absence violates a basic human right.

Similarly, there is broad agreement on the importance of ensuring universal access to quality education to address chronic poverty and break the cycle of intergenerational transmission. The challenge is not only to secure the massive investments needed to improve access and quality, but also to ensure that education serves to level the playing field rather than to reinforce inequality. Too often, investments meant to improve the quality of education benefit wealthy families the most, even under conditions of near-universal coverage. In general, ensuring funding for the expansion of quality primary education and enforcing compulsory schooling up to the lower secondary level have helped boost access for children living in poverty, as has the universal provision of preprimary schooling.

Managing risk and building resilience are increasingly important in the current context of rapid economic, environmental and geopolitical transformations. At this critical juncture, accelerating progress towards poverty eradication calls for doing more to integrate analysis and policy making, not only across the social, economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable development, but also between development and peace-building efforts. A focus on the links between poverty and conflict highlights the role of governance and the importance of building institutional capacity to prevent conflict and ensure that countries emerging from conflict can make sustained progress towards eradicating poverty. Doing so requires pursuing long-term goals to ensure, for instance, that countries have effective justice systems or an adequately trained civil service. Investments to build people’s resilience will not have the desired effects if a State’s capacity to implement policies or enforce regulations is limited.

As regards policy integration across the three dimensions of sustainable development, climate change mitigation and adaptation measures are critical for preventing falls into poverty. Yet efforts to eradicate poverty can be significantly constrained by measures aimed at limiting or mitigating climate change, especially if the rights of workers and people’s livelihoods are not protected as countries embark on the energy transition and as economies shift towards sustainable production patterns – that is, if the transition is not just. Although a holistic approach to sustainable development is at the heart of the 2030 Agenda, many countries have yet to put in place the integrated decision-making needed to manage trade-offs and ensure that efforts to achieve environmental goals, economic transformation and poverty eradication are well coordinated and mutually reinforcing.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations