Ten years ago, the United Nations celebrated the International Year of Small Island Developing States (SIDS). In the same year, the SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action (SAMOA) Pathway, an ambitious 10-year action plan for SIDS, was adopted at the Third International Conference on SIDS held in Apia, Samoa, in 2014. The SAMOA Pathway identifies critical linkages between population and development in island states, most notably in the areas of health, gender equality and women’s rights and on the role of migrants in enhancing development in their communities of origin. Many of these linkages are also highlighted in the Antigua and Barbuda Agenda for SIDS (ABAS), along with emerging demographic issues that present new challenges and opportunities for the sustainable development of SIDS.

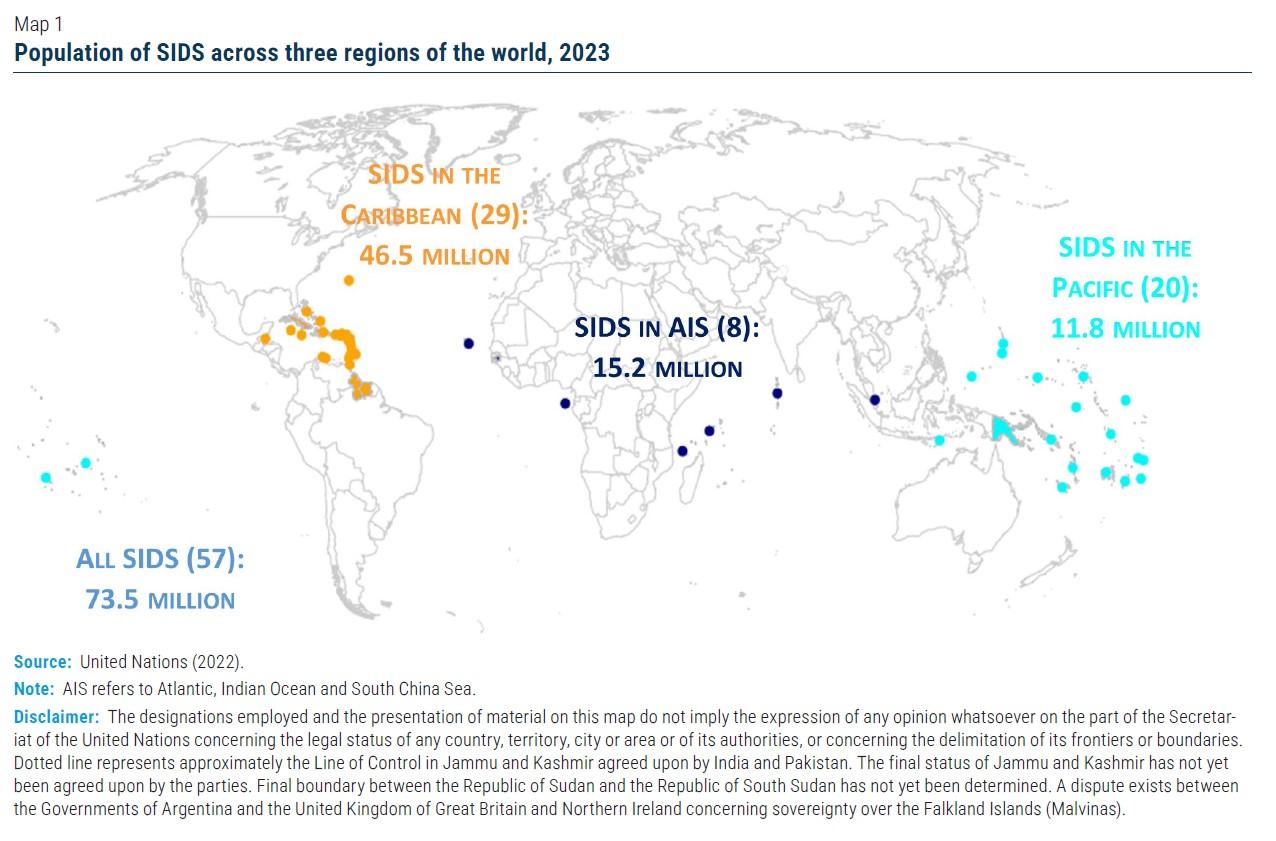

The small island developing States (SIDS) are a heterogeneous group of island and coastal states and territories spread across the world. As of June 2023, the group was composed of 57 countries and territories with a combined population of 73.5 million. While 46 SIDS have small populations of under 1 million, Papua New Guinea and three nations of the Greater Antilles – Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Haiti – have more than 10 million inhabitants each and accounted for around 60 per cent of the group’s population in 2023.

POPULATION GROWTH IN SIDS IS SLOWING DOWN

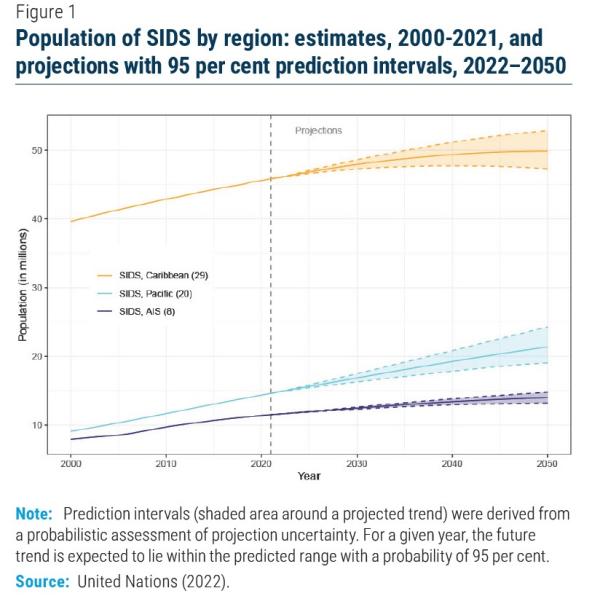

The population of SIDS is expected to continue growing, albeit at a progressively slower pace, and is projected to reach 85.4 million in 2050. Half of the increase in population through 2050 will be concentrated in the Pacific region, which has the highest levels of fertility among the regional groupings of SIDS. By contrast, the populations of 14 SIDS, located mostly in the Caribbean or Pacific regions, are declining in size or growing at annual rates of less than 0.1 per cent. By 2050, 19 of the 57 SIDS are projected to have declining populations.

HALF OF THE GROWTH IN THE TOTAL POPULATION OF SIDS WILL OCCUR IN THE PACIFIC REGION

While just over half (29) of the 57 SIDS are in the Caribbean, the region contains well over half (46.5 million) of the group’s total population of 73.5 million (figure 1). The populations of SIDS in the Pacific region and in the Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean and South China Sea (AIS) had comparable sizes in 2023, with 15.3 and 11.8 million, respectively. The most populous SIDS are Haiti (12 million), the Dominican Republic (11 million) and Cuba (11 million) in the Caribbean, Papua New Guinea (10 million) in the Pacific, and Singapore (6 million) in the AIS region.

From 2023 to 2050, the number of people living in SIDS is expected to grow by 16 per cent or almost 12 million people, rising from 73.5 to 85.4 million. Half of this increase will take place in the Pacific region. Even though Caribbean SIDS will continue to dominate the group in population size, their share of the total population is expected to drop from 63 to 58 per cent, while the share of those in the Pacific region will increase from 21 to 25 per cent, and for those in the AIS region, from 16 to 18 per cent.

THERE ARE MARKED DIFFERENCES IN SIDS FERTILITY RATES ACROSS COUNTRIES AND REGIONS

An estimated 1.2 million live births occurred in SIDS during 2022, a number that is not expected to change much through 2050. As a group, SIDS had a total fertility rate of 2.3 live births per woman in 2022, with marked differences across countries and regions (figure 2.a). In the Pacific, for example, fertility was about four births per woman in Solomon Islands and Samoa but below the replacement level in French Polynesia and New Caledonia. The two countries sharing the island of Hispaniola, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, had some of the highest levels of fertility in the Caribbean in 2022, whereas Cuba and some of the smaller islands had some of the lowest levels.3 In the AIS grouping, fertility was the lowest in Singapore, with 1 birth per woman on average in 2022, and close to 4 in Guinea-Bissau. Policies affecting childbearing should be aligned with the reproductive aspirations of the population and help to ensure that the desires of individuals and couples are fulfilled. For SIDS where there is concern about low fertility, the family support policies implemented with varying degrees of success in other low-fertility countries can inform the formulation of national policies and programmes.

CONTINUING INVESTMENTS IN THE PREVENTION, EARLY DETECTION AND TREATMENT OF NCDS ARE CRUCIAL TO REDUCE PREMATURE DEATHS

The level of life expectancy at birth for SIDS as a group was estimated at 72.3 years in 2022 (75.4 for women, 69.5 for men) and was projected to increase further to around 77 years in 2050 (figure 2.b). In the AIS grouping, life expectancy was 76 years in 2022, the highest among the three regional groupings, due mainly to Singapore’s high level of life expectancy. In 2022, life expectancy in Caribbean SIDS was 73 years, while for SIDS in the Pacific region, it stood at 68 years. One small island developing State in the Caribbean region and four SIDS in the Pacific region are unlikely to achieve SDG target 3.24 on child mortality by 2030 unless further measures are put in place to end preventable child deaths.

The SAMOA Pathway and the ABAS recognize that noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) pose a major callenge for SIDS, which are characterized by a high prevalence of associated risk factors such as tobacco use, unhealthy diets, harmful use of alcohol, physical inactivity and air pollution.

As a result, the populations of SIDS are disproportionally affected by NCD-related premature mortality (WHO, 2023). In 2019, nine SIDS, mostly located in the Pacific were among the 20 countries with the highest mortality rates attributable to cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes or chronic respiratory disease. Addressing and preventing NCDs requires increased access to quality services and medicines throughout the life course while reducing exposure to risk factors. Strengthening primary health-care services, especially in remote islands, is needed to achieve universal health coverage.

AGEING POPULATIONS NECESSITATE ROBUST SOCIAL PROTECTION SYSTEMS AND OTHER POLICIES TO ENSURE THE WELL-BEING OF OLDER PERSONS

Population ageing signals our extraordinary collective success in improving living conditions for billions of people around the world. Broadly defined as a gradual increase in the share of older persons in a population, it occurs as a consequence of the demographic transition and can be exacerbated by persistently high levels of outmigration, particularly of young people. In almost two thirds of SIDS (37 of 57), the older population, defined here as persons aged 65 years or over, represented more than 7 per cent of the group’s total population in 2023. An additional 16 countries are expected to reach this benchmark between 2023 and 2050, with four more anticipated to do so in the second half of the century. Population ageing in SIDS of the Caribbean is more advanced than in those of the Pacific and AIS regions. In 2023, 90 per cent of SIDS in the Caribbean, and about 40 per cent of SIDS in the Pacific and AIS groupings, had older populations comprising at least 7 per cent of the total population.

Anticipating the rate of increase in the proportion of older persons is essential for societies to adapt to changing age distributions, to assess their prospects for benefitting from the demographic dividend, and to implement adequate policies that meet the needs of different age groups (United Nations, 2023b). The amount of time required for the share of the older population to double (here from 7 to 14 per cent) is sometimes used as an indicator of the speed of population ageing. For SIDS in the Caribbean, this transition is taking, or will take, about 45 years on average. For most SIDS in the Pacific and AIS regions, this transition has happened or is expected to happen later and faster than in the Caribbean, with considerable variation in timing and speed.

Comprehensive social protection systems, including affordable health care for older persons, pension schemes, and long-term care services, are essential to safeguard the dignity of older persons. Community-based initiatives can bridge gaps in services, particularly in remote islands where centralized support is limited. The varying health profiles across SIDS require targeted health-care strategies to provide specialized care for ageing populations.

INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION CAN BE HARNESSED FOR THE BENEFIT OF INDIVIDUALS, FAMILIES AND SOCIETIES

Factors such as geographical isolation, limited resources and susceptibility to climate change have contributed to high levels of internal and international migration in SIDS, both historically and in recent years. With high proportions of the population living in coastal areas, many of which are lowlands, coastal floods, storm surges and inland flooding have forced large numbers of SIDS residents to resettle internally or migrate abroad. Socio-economic fragility and lack of opportunity are also driving emigration from SIDS, with the emigration of skilled professionals creating a “brain drain” that has become a major cause of concern in many countries (SDG targets 3.c, 4.b and 4.c; SDG 13) (Campbell and Warrick, 2014; OECD, 2018). Patterns of human mobility from SIDS have also been shaped by the special status of current island territories, associated states and former colonies. Moreover, some SIDS economies depend heavily on the inflow of migrant remittances, with such transfers representing more than 20 per cent of GDP in Bermuda, Comoros, Haiti, Jamaica, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu.

The total number of migrants from SIDS living abroad provides an estimate of the size of the SIDS diaspora population. As of 2020, there were 11.5 million people from SIDS residing outside their country or area of birth (United Nations, 2020). The SIDS diaspora is largely dominated by Among the 36 SIDS with available data for years 2020, 2021 or 2022. migrants from the Caribbean region, who in 2020 accounted for 86 per cent of the international migrants originating from SIDS. For nearly half of the Caribbean States, the diaspora population in 2020 exceeded 30 per cent of the country’s resident population. More than two thirds of the diaspora communities from Caribbean SIDS were located in the United States of America in 2020, with another 14 per cent found in other Caribbean or Latin American countries and 8 per cent in Canada or the United Kingdom. Migrants from the Pacific SIDS accounted for 9 per cent of the global SIDS diaspora population in 2020, with most living in the Pacific region, especially in New Zealand and Australia (55 per cent). The diaspora from the eight SIDS in the AIS region accounted in 2020 for 5 per cent of the international migrants originating from SIDS. Policies that encourage diaspora engagement in countries of origin, skills transfer and productive investment of remittances can mitigate some of the challenges associated with large-scale outmigration. Promoting the retention of skills, reducing brain drain, and encouraging circular migration and return of migrants with needed skills can enhance local productive capacities and contribute to a more sustainable future.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations