What are middle-income countries?

What are middle-income countries?

Middle-income countries (MICs) are those whose incomes per capita lie between the levels used to define low- and high- income countries, with thresholds established by the World Bank. As of 1 July 2023, the group comprises 108 countries with a gross national income per capita of between $1,136 and $13,845. Together, MICs account for about 30 per cent of global GDP and make up 75 per cent of the world’s population, including 60 per cent of the world’s poor. The MICs classification overlaps with other country groupings. Currently, 22 least developed countries, 20 landlocked developing countries and 27 small island developing States are also classed as MICs. Among all MICs, 12 are ranked as having a “very high” Human Development Index, 44 as “high”, 42 as “medium” and 9 as “low”. The reliance on an income-only criterion for classification means that there have been situations when countries moved into and out of the MICs group. Between late 2000 and late 2023, 25 countries transitioned from the middle-income to the high-income group, including many former centrally planned economies in Eastern Europe and some small island developing States. These transitions were often far from smooth, with many countries crossing back and forth multiple times (there were 46 transitions from middle- to high-income and 21 transitions in the opposite direction). At the same time, 39 countries transitioned from low- to middle-income status, and there were fewer instances of reverse transitions. Most recently, the pandemic downturn caused three countries to fall from high- to middle-income in late 2021 (based on 2020 GNI per capita), only one of which bounced back by late 2023. At the same time, access to certain kinds of concessional finance from multilateral development banks depends on the income grouping a country belongs to. For example, eligibility to receive grants or concessional loans from the World Bank’s International Development Association is limited to low-income countries (those with per capita incomes up to $1,135). This policy brief reviews current and longer-term challenges of MICs to achieve sustainable development; possible pathways to emerge from these challenges; and international development support for MICs. It puts forward recommendations for policy action at the national and international levels, based on the 2023 report of the Secretary-General on development cooperation with middle-income countries (A/78/224).

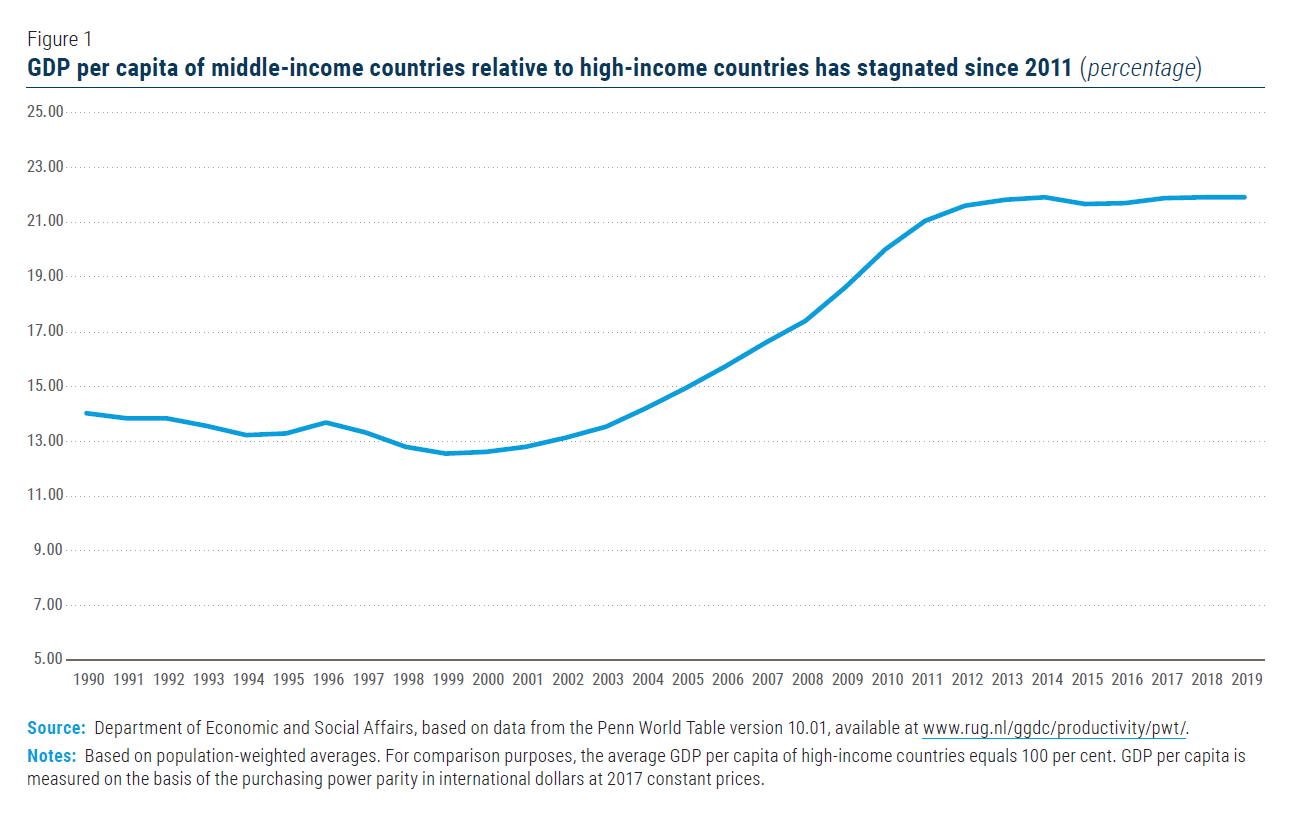

Stagnating economic progress

The recent confluence of crises has shone a spotlight on the development challenges of MICs, which had been building for a while. Even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth momentum in MICs had been slowing. After a period of rapid convergence with high-income countries, starting in the early 2000s (and driven by a few fast-growing upper-middle income countries), the growth momentum began to slacken from 2010 onward (see figure 1). This apparent plateauing – instead of converging – has been attributed to difficulties in switching growth models as countries move up the income ladder, from one that is based on cheap labour, increased capital accumulation and basic technology catch-up to one that is driven by innovation and productivity growth. While the concept of a “middle-income trap” has been useful for analysing the underlying growth barriers and assessing policy options to help MICs achieve sustainable development, it should be emphasized that there is considerable variation in growth rates between individual countries. The pandemic and subsequent shocks from the war in Ukraine and climate-related disasters hit MICs hard. The loss of livelihoods, increased costs of living and heightened food insecurity in many MICs has pushed millions into poverty. The monetary policy responses to inflation in advanced economies have triggered capital outflows and currency depreciations that have led to increasing balance of payment pressures, higher debt-servicing costs, and growing risks to debt sustainability in several MICs. In 2022, the average public debt-to-GDP ratio in MICs rose to a record 65 per cent. Growing debt service costs and a lack of access to long-term affordable financing are progressively crowding out investments in sustainable development and climate action.

A multi-dimensional assessment of development

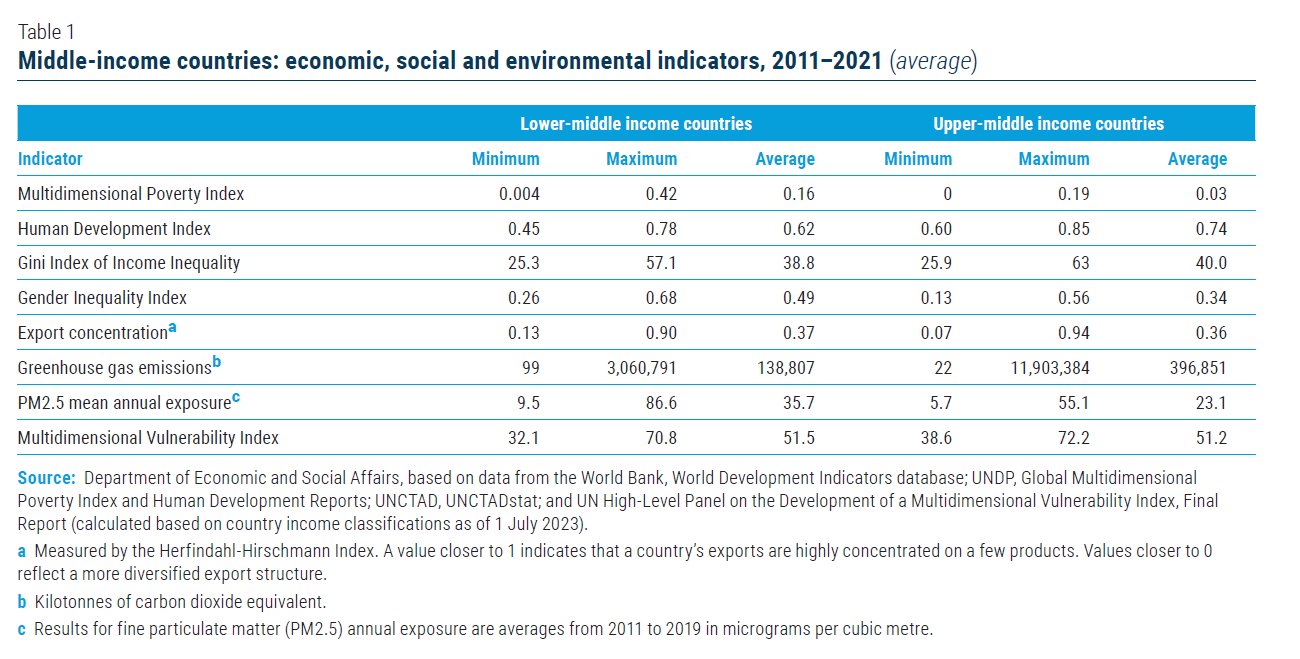

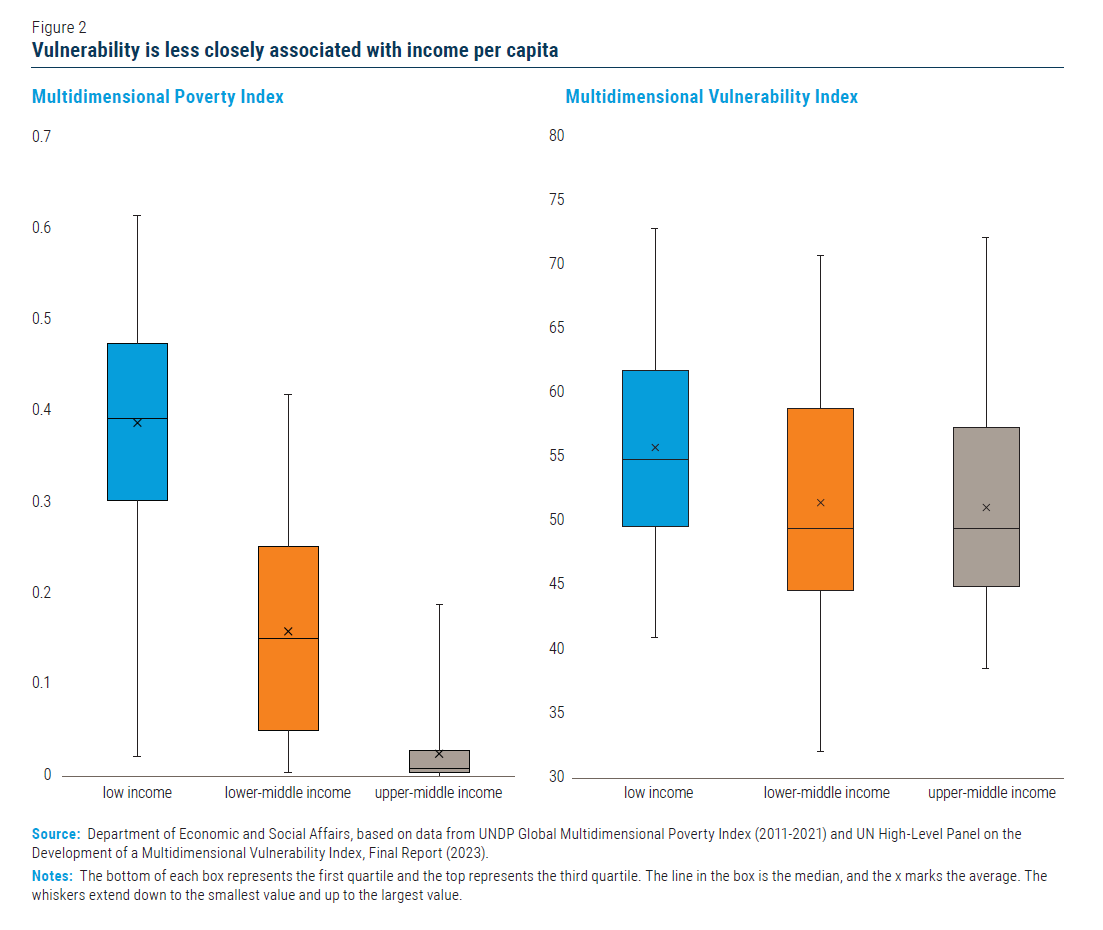

MICs are a highly heterogeneous group of countries, as apparent even if only the income per capita metric is used. Yet, other measures help to better understand MICs’ multidimensional development achievements and needs. MICs differ vastly across a broad range of economic, social and environmental development indicators, such as multidimensional poverty, income and gender inequality, export concentration, and greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, within the subgroup of lower-middle income countries, the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) values range from less than 0.01 to 0.42, with an average of 0.16. The MPI average is lower for upper-middle income countries, at 0.03, but the highest value in that group is 0.19, which is higher than the average in the lower-middle income group (see table 1). Export concentration is only marginally higher, on average, for lower-middle income countries than for upper-middle income countries (0.37 and 0.36, respectively), with both subgroups showing great dispersion between extremes.  Compared to low income countries, MICs experience lower multidimensional poverty, on average, but the large dispersion among MICs – especially the lower-middle income countries – means that multidimensional poverty in some MICs is higher than in the first and second quartiles of low income countries. The structural vulnerability and resilience of countries, as measured by the Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI), is less closely associated with income per capita. While MICs have lower MVI values than low-income countries, on average, there is a large overlap between income groups, and the dispersion within groups is much larger than between groups (see figure 2). The heterogeneity across the indicators reflects different development gaps that are rooted in countries’ individual circumstances. A careful analysis of these gaps, and their interactions with current challenges (including growing public debt and shrinking fiscal space), should form the basis for both domestic policy choices and international cooperation. The identification and targeting of country-specific development bottlenecks – instead of a narrow focus on income per capita alone – is a vital part of transitioning to a sustainable growth model. The proposed MVI and other measures that go beyond GDP can be valuable tools in this context (see below).

Compared to low income countries, MICs experience lower multidimensional poverty, on average, but the large dispersion among MICs – especially the lower-middle income countries – means that multidimensional poverty in some MICs is higher than in the first and second quartiles of low income countries. The structural vulnerability and resilience of countries, as measured by the Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI), is less closely associated with income per capita. While MICs have lower MVI values than low-income countries, on average, there is a large overlap between income groups, and the dispersion within groups is much larger than between groups (see figure 2). The heterogeneity across the indicators reflects different development gaps that are rooted in countries’ individual circumstances. A careful analysis of these gaps, and their interactions with current challenges (including growing public debt and shrinking fiscal space), should form the basis for both domestic policy choices and international cooperation. The identification and targeting of country-specific development bottlenecks – instead of a narrow focus on income per capita alone – is a vital part of transitioning to a sustainable growth model. The proposed MVI and other measures that go beyond GDP can be valuable tools in this context (see below).  Despite their many differences, MICs also seek to meet common aspirations while contending with similar challenges. Eradicating poverty and other deprivations, reducing inequalities, and generating employment while maintaining climate and environment commitments mean that conventional development pathways that were followed in the past may no longer be fully appropriate. In addition, multiple and overlapping crises coupled with the worsening impacts of climate change are causing setbacks to progress. To achieve sustainable development in its economic, social and environmental dimensions, MICs need to transition to inclusive and sustainable growth models, according to their specific circumstances, that are more resource and energy efficient and driven by innovation and productivity growth. Many MICs will require international support for these transitions, through financing (including debt relief and concessional financing), technology transfer, and capacity-building. Development cooperation should be tailored to MICs’ development needs and priorities, based on systematic assessments and indicators that go beyond GDP.

Despite their many differences, MICs also seek to meet common aspirations while contending with similar challenges. Eradicating poverty and other deprivations, reducing inequalities, and generating employment while maintaining climate and environment commitments mean that conventional development pathways that were followed in the past may no longer be fully appropriate. In addition, multiple and overlapping crises coupled with the worsening impacts of climate change are causing setbacks to progress. To achieve sustainable development in its economic, social and environmental dimensions, MICs need to transition to inclusive and sustainable growth models, according to their specific circumstances, that are more resource and energy efficient and driven by innovation and productivity growth. Many MICs will require international support for these transitions, through financing (including debt relief and concessional financing), technology transfer, and capacity-building. Development cooperation should be tailored to MICs’ development needs and priorities, based on systematic assessments and indicators that go beyond GDP.

Current support available to MICs

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognizes that – while each country has primary responsibility for its own economic and social development – the SDGs will not be achieved without a revitalized and enhanced Global Partnership. It recognizes the challenges of MICs to achieve sustainable development and calls for better and focused support from the United Nations development system and the international financial institutions, among others. A recent mapping of current support available to MICs showed that the United Nations development system works closely with these countries, based on a wide range of indices, frameworks, strategies and tools that include, but also go beyond income per capita. In 2021, UN development system spending in MICs reached $17.2 billion, around 52 per cent of all country allocable spending. On a per capita basis, however, spending on MICs was significantly lower than for other country groups, at $2.95 (compared to $19.19 for small island developing States, $16.62 for landlocked developing countries and $16.03 for least developed countries). Feedback from MICs on the support from the UN development system was generally positive and has improved since the repositioning of the system. Areas for improvement include enhanced support for integrated national financing frameworks and for mobilizing additional financing for achieving the SDGs. Eligibility for official development assistance (ODA) is determined by the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD, and is mainly based on income per capita. Countries that cross the high-income threshold for three consecutive years and “graduate” from ODA eligibility can still receive concessional finance, although it is no longer registered as ODA. The modality of ODA often changes before graduation, with MICs receiving a larger share in the form of loans rather than grants, and greater donor interest in issue-specific allocations, such as climate change mitigation or humanitarian aid for refugees. In 2021, gross disbursements of ODA for MICs reached $111.4 billion, around 47 per cent of total ODA. Most MICs don’t meet the income-based eligibility criteria for concessional financing from multilateral development banks (MDBs), although many MDBs have included additional criteria – such as vulnerability – in recent years, on an ad hoc basis. Non-concessional financing from MDBs can still play an important role in boosting sustainable development investment in MICs, through long-term loans at below-market interest rates, usually combined with technical support. In 2021, other official flows (OOF, official flows that do not meet ODA criteria) from MDBs to MICs reached $83.5 billion, around 92 per cent of total OOF from MDBs. In 2020, developed countries provided and mobilized $83.3 billion for climate action in developing countries, falling short of their pledge of $100 billion per year by 2020 (which may be reached in 2023). Over 80 per cent of this was disbursed to MICs, mainly in the form of loans. Overall, around two thirds of international public climate finance is disbursed as loans, at different degrees of conditionality, with a higher share of grant financing for adaptation than for mitigation. National policies and international support for achieving sustainable development in middle-income countries Sustained per capita economic growth is an integral part of sustainable development, as recognized in the 2030 Agenda. Yet, many MICs have not been able to maintain growth dynamics over time, as they struggle to overcome long-term development gaps and address current crises. MICs also suffer from high levels of inequality, as old growth models have left many behind. At the same time, MICs face growing challenges from the adverse effects of climate change, biodiversity loss and growing pollution that cast doubts on the validity of traditional development pathways. National policymakers need to design and implement coherent and consistent policy measures to recover from current crises and ensure long-term, inclusive and sustainable growth. International development cooperation will be needed both in the short term and to support longer-term transformations. Both national policies and international cooperation should be based on systematic needs assessments and indicators that go beyond GDP.

National policies for successful transitions

To achieve sustained long-term and inclusive growth as they move up the income ladder, MICs need to switch growth models from one that is based on cheap labour, increased capital accumulation and basic technology catch-up, to one that is driven by innovation and productivity growth. This requires targeting country-specific development gaps, such as high levels of inequality, weak education and health systems, high degrees of commodity dependence and export concentration, and environmental and economic vulnerabilities, among others. To overcome environmental challenges, MICs also need to embark on just and inclusive green transitions, in tandem with international efforts, led by high-income countries, to bring down global GHG emissions. This includes moving towards more sustainable consumption and production and shifting towards a more digital, knowledge-based economy that is more resource and energy efficient. This could also help raise productivity levels and ensure longer-term growth prospects.

International support for recovery and sustainable development

Many MICs will require international support to recover from current crises and/or to successfully manage the necessary sustainable and inclusive growth transitions. Development cooperation should be tailored to MICs’ specific development needs and priorities, and not be guided uniquely by income-based criteria. To address growing sovereign debt burdens that have or may soon become unsustainable in several MICs and that are already crowding out investments in sustainable development and climate action, the international community must act immediately. Needed actions include setting up a debt workout mechanism, for example at a multilateral development bank, and making greater use of debt-for-SDG or debt-for-climate swaps and of risk-sharing debt instruments. Additional efforts are needed for long-term comprehensive and structural solutions to sovereign debt challenges, including through long overdue reforms of the international debt architecture. MICs also need access to long-term affordable financing for their transition to sustainable and inclusive growth models and to achieve the SDGs. The United Nations development system should enhance its support for integrated national financing frameworks at the country level, and help to translate into reality initiatives such as a Sustainable Development Goal stimulus and reform of the international financial architecture at the global level. International support for MICs’ just and inclusive green transitions – including financing, technology transfer and capacity-building – should in large part be on highly concessional terms, to account for positive global externalities. Increased financing for the mitigation of climate change and preservation of biodiversity and other global public goods must not, however, crowd out the financing of sustainable development in developing countries. Rather, donors need to step up efforts to reach their commitment to provide 0.7 per cent of GNI as ODA and allocate 0.15-0.20 per cent of GNI to least developed countries.

Multidimensional measuring approaches

The multidimensional development achievements and challenges of MICs cannot be adequately captured by income-based measures alone. A more tailored approach should include an assessment of each country’s specific development gaps, multidimensional vulnerabilities, and capabilities to mobilize resources, among others. The international community should continue to pursue new approaches that go beyond GDP, which could inform both domestic policy decisions and international development cooperation, including access to concessional finance. The proposed MVI is designed to measure structural vulnerability and lack of resilience across multiple dimensions of sustainable development at the national level, which could provide additional insight into countries’ development needs. It could help the UN development system to integrate vulnerability and resilience in a more systematic manner across its global, regional, and national programmes. Multilateral development banks should also explore possible use cases for MVI, including to determine eligibility for concessional finance, and the OECD Development Assistance Committee should consider whether and how it could be used to determine ODA eligibility and graduation. As part of the Political Declaration of the 2023 SDG Summit, Member States confirmed their commitment to explore measures that complement or go beyond GDP and encouraged the international community to consider multidimensional vulnerability as criteria to access concessional finance.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations