Beneficial ownership information: Supporting fair taxation and financial integrity

Beneficial ownership information: Supporting fair taxation and financial integrity

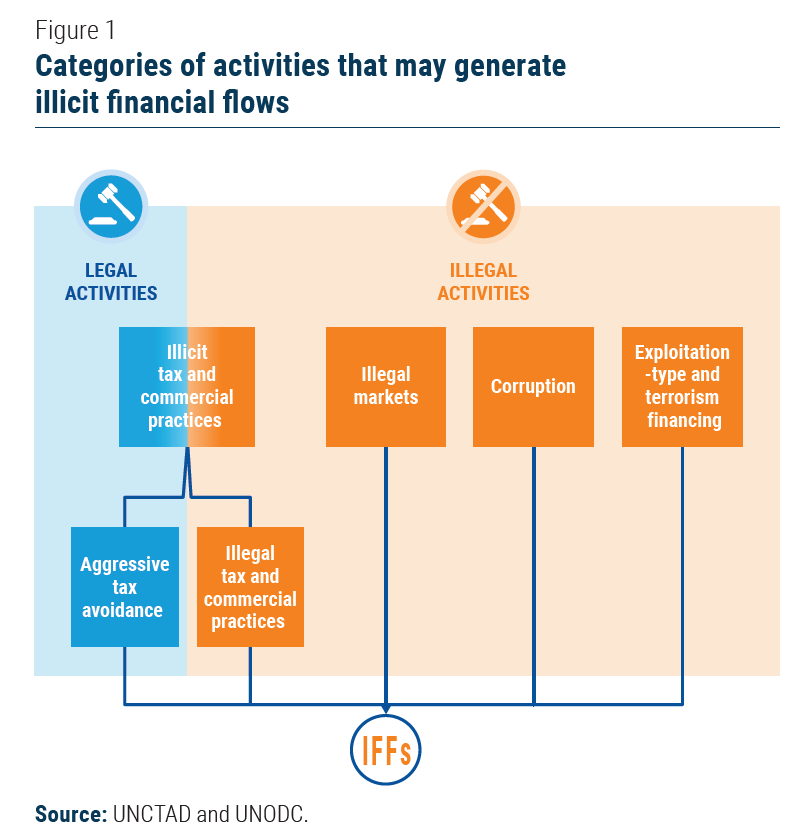

Domestic public finance is essential to financing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), providing public goods and services, increasing equity, and helping manage macroeconomic stability. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda places domestic resource mobilization at the core of the actions that countries need to take to deliver sustainable development. Countries have been working to increase revenues so that they can invest in the SDGs, but tax avoidance, tax evasion and corruption are undermining countries’ efforts. Illicit financial flow (IFF) is the term that covers these activities (see Figure 1) that cross borders and reduce the availability of resources for financing sustainable development, including recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Addis Agenda, Member States committed to eliminate IFFs. Since 2015, they have taken many actions to boost transparency and combat IFFs, but there is more work to be done. Eliminating IFFs will require further actions across the sphere of national and global governance as well as international cooperation. Transparency about the actors in economic and financial matters is an essential component in the ability of country authorities to enforce the law, reduce corruption and ensure taxpayers pay all taxes that are due. Increasing the accuracy and transparency of beneficial ownership information is an important component of solutions for reducing tax avoidance and evasion and combatting corruption and money-laundering.  International anti-money laundering standards, applicable to the vast majority of countries, were recently updated to require a public authority or body functioning as beneficial ownership registry to hold beneficial ownership information. Policy makers and other stakeholders should understand the changes; how the enhanced beneficial ownership transparency can help reduce tax abuses, corruption, and money-laundering; and possible future steps to invest in strengthening financial integrity.

International anti-money laundering standards, applicable to the vast majority of countries, were recently updated to require a public authority or body functioning as beneficial ownership registry to hold beneficial ownership information. Policy makers and other stakeholders should understand the changes; how the enhanced beneficial ownership transparency can help reduce tax abuses, corruption, and money-laundering; and possible future steps to invest in strengthening financial integrity.

Background

The concept of beneficial ownership, though with some variations, is used in three main areas: anti-money laundering rules, tax transparency instruments and tax treaties (see box). The origin of the term “beneficial owner” has been traced to the United Kingdom almost 1,000 years ago. At the time trusts were created for the benefit of the families of soldiers and warriors who left the country to fight in religious wars. This is the first recorded instance of separation of legal ownership from beneficial ownership. The trustees become the legal owners, while the men were the beneficial owners and the families would be the beneficiaries of the trusts. These days the concept has been broadened and used in international frameworks related to taxation and anti-money laundering. Criminals and tax dodgers commonly rely on secrecy to disguise or hide their activity and often use opaque legal structures to this end. Money-laundering involves processing of the proceeds of crimes to disguise their illegal origin. Before the March 2022 changes to international anti-money laundering standards, in most countries, only the “legal owners” of an asset or legal vehicle (e.g. a company) were known. The legal owner may refer to another legal vehicle (such as company, partnership or trust) or to a nominee, meaning accountability cannot be ensured. Tax evasion, harmful international tax planning and money laundering commonly create secrecy by layering of ownership through subsidiaries, corporations, trusts, investment funds and/or other legal vehicles to conceal the true ownership. Often “shell companies”, which are corporate entities that have no independent activities, are set up only to own assets and other corporate entities. Transactions are spread across multiple jurisdictions, and may involve the ownership of assets for which there is no regulation or weak recording of ownership, and the creation of complex ownership chains involving multiple types of legal vehicles. The scale of illicit financial flows has been estimated to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Beneficial ownership transparency can reveal the true ownership and allow fair taxation and enforcement of the law. For anti-money-laundering purposes, the beneficial owner is the natural person who ultimately owns, controls or benefits from legal vehicles such as companies, partnerships and trusts. Collection of this information is a way to help lift the veil of secrecy that perpetrators of IFFs use to conceal their activities. This information can help officials investigate and eventually prosecute financial crimes and other abuses. Before March 2022 international norms required country authorities to have access to beneficial ownership information “in a timely fashion” for both types of legal vehicles – legal persons (e.g., companies) and legal arrangements (e.g., trusts). Countries had been strengthening their approaches to try to have better access to information, but accurate information was often not readily available to authorities. In March 2022, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) amended its recommendation on beneficial ownership information of legal persons to require a public authority to hold this information (usually through a registry). This will apply to the more than 200 countries and jurisdictions committed to FATF standards.

Areas for reform and potential benefits

The veil of secrecy used by the perpetrators of IFFs can be pierced only if authorities require the maintenance of beneficial ownership information across asset types, ownership structures and jurisdictions. Benefits can be found in the three main areas identified above: anti-money laundering rules, tax transparency instruments and tax treaties.

Countering corruption and money-laundering

Beneficial ownership transparency can reveal that apparently legitimate and unrelated companies and trusts are in fact part of a public sector corruption scheme. Routine due diligence for public procurement or audits of public expenditure might not identify corruption schemes if beneficial ownership is disguised by impenetrable layers of legal ownership. Having readily available beneficial ownership information, including across borders, can ensure that such audits discover public corruption. This can also have a deterrent effect, enhancing efforts at corruption prevention. Country authorities can also make use of beneficial ownership information for other purposes than deterrence and prosecution. Beneficial ownership information in other jurisdictions, particularly in popular destinations for the proceeds of crime and corruption, will be valuable in finding the assets of criminals for purposes of confiscation and ultimately return to the country of origin. In the private sector, beneficial ownership information can enhance trust in business partnerships and reduce fraud by helping companies conduct their own due diligence on the entities with which they do business.

Countering tax abuses: Uses of beneficial ownership information in tax transparency

In the last decade significant progress has been made in requiring financial institutions to identify the beneficial owners of financial accounts and developing a system for reporting this information to authorities. This can help ensure the correct assignment of tax liabilities and allow fair taxation. International efforts to improve cross-border sharing of beneficial ownership information, including through the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, allow participating countries to receive information needed to launch tax audits when they discover undeclared offshore assets. Unfortunately, developing countries lag behind in the automatic receipt of information from this system for a variety of reasons, for example insufficient taxpayer confidentiality protections in the tax administration processes. While 46 developing jurisdictions are actively participating or are committed to doing so in the near future, no least developed countries (LDCs) are currently receiving information via this initiative.

Countering tax abuses: Uses of beneficial ownership information in tax treaties

Countering tax abuses: Uses of beneficial ownership information in tax treaties

Tax treaties provide benefits to taxpayers by putting limits on the rights of countries to tax income that arises within their borders. A developing country may be willing to enter into such an agreement because it believes that it will attract increased investment by residents of the other party to the agreement. However, developing countries entering into tax treaties should be aware of the need to prevent “treaty-shopping” by residents of third countries. Such third-country residents, who are not eligible for benefits of the treaty, may establish a layered transaction or shell company in hopes of claiming the benefits. If such efforts succeed, the developing country may lose substantially more revenue than it expected The “beneficial owner” concept in tax treaties is one way of addressing treaty-shopping. Over the past decade or so, tax treaties have increasingly included more powerful anti-treaty-shopping provisions. All such anti-treaty-shopping rules, however, will only be effective to prevent abuse of tax treaties if developing countries have information regarding the tiers of legal ownership that often exist beyond the legal owner of income. Measures to increase access to such ownership information therefore can assist developing countries in reducing tax leakage to third countries.

Policy solutions for the future

Creating beneficial ownership registries

To reduce abuse, beneficial ownership regimes on legal entities should be as consistent as possible across countries. All countries committed to implementing the FATF standards will need to update their domestic legal frameworks to meet the new recommendations. Developing countries struggling with IFFs will benefit by creating registries of beneficial ownership information of legal persons such as companies. It is in their interests to move as fast as possible to implement registries, given the potential gains in tax revenues and reduced corruption. Digital technologies, some of which have been exploited by criminals in conducting financial crimes, can also be used to enhance such registries to further the fight against IFFs. At the national level registries should be accessible to all law enforcement agencies, including anti-corruption bodies, tax administrations and customs authorities. Capacity constraints in developing countries will have to be addressed, and there is a role for donor countries to finance the upgrading of systems in developing countries, especially LDCs. International organizations are also available to assist countries.

Strengthening registries with verification

First, while the FATF standards require that beneficial ownership information is accurate, the information is rarely verified. If criminals give deliberately false information, it undermines the value of beneficial ownership transparency. In December 2021, a UN body “encourage[d] States parties to consider developing effective mechanisms for relevant domestic authorities or entities to verify or check beneficial ownership information provided by legal persons and legal arrangements.” To determine the beneficial owners, where necessary, countries should take additional measures beyond relying on the declarations of legal vehicles themselves. Verification should ideally include authentication (making sure the beneficial owner is who they say they are), authorisation (ensuring that the individual consents to involvement with the legal vehicle), and validation (to prevent mistakes and deliberate falsehoods). Technological tools to detect patterns and signs of high-risk entries can help identify fraud or abuse. A handful of countries have demonstrated successful validation tools and cross-checks with other databases. In developed countries there are well-developed information systems and architectures which could be used for cross validation of information if the legal framework allows (e.g., tax administration system, national identification database or social insurance systems). However, some developing countries lack the secure information architecture to successfully verify information. Again, donors can play a role in financing the creation of these capacities.

Expanding the scope of coverage (e.g. legal arrangements, non-financial assets)

The updated FATF beneficial ownership standards only strengthened the requirements for legal entities (e.g. companies) and not trusts and other similar legal arrangements, leaving secrecy loopholes, yet this may change in the near future. In June 2022, FATF opened a public consultation on potential revisions to its standards to address the way legal arrangements are covered. Regardless of the outcome of the FATF consultation, countries may wish to move forward faster with a registry approach to beneficial ownership information for all legal arrangements. Many countries already have in place limited trust registration requirements, which can be strengthened. Countries are also experimenting with creating registries for other kinds of high-value assets that can be used to store illicitly acquired wealth.

Exchanging information based on consistent standards

Despite the global standards, beneficial ownership definitions in national regulations vary. Often there is a threshold for declaring ownership on a registry or through other information schemes, yet in other countries there are no thresholds at all. One common policy is a “greater than 25 per cent” threshold for ownership or voting rights. In practice this condition is easy to avoid by splitting ownership among associates. Further, some legal frameworks fail to distinguish among different ownership definitions based on the legal entity type, creating loopholes. Member States may wish to take measures for greater harmonization of the implementation of the standards over time. Cross-border information access is generally difficult and time-consuming. The Egmont Group, a network for financial intelligence units, has a framework for exchanges of information related to money-laundering. There are also bilateral, regional and multilateral frameworks setting standards for the exchange of information for tax purposes, for example within the European Union and through the Global Forum (see box), though these tend to focus on financial account ownership. However, many requests for information will not be covered by automatic exchange arrangements and must be handled through bilateral cooperation requests. This requires countries to have in place the necessary legal framework authorizing such an exchange of information. The processing of the request necessitates resources, both for the requesting country, who must substantiate the reason for a request, and the responding country, to find actionable information and send it. Major financial centres and developed countries, where many legal vehicles are incorporated and where most of the cross-border assets and wealth are held, should develop sufficient capacity in their relevant public authorities to handle such requests expeditiously. Having single contact points and clear procedures can help ensure timely responses to requests for information.

Public information availability

A growing number of countries – such as Albania, Ghana, Indonesia, and Zambia – are creating systems to publish their beneficial ownership registries for public access, with appropriate privacy protections. Such enhanced transparency is beneficial to speeding up national and international information-sharing. It can also assist due diligence by the private sector, allowing more effective accountability. Public transparency of this information can also boost trust more broadly and contribute to strengthening the social contract.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations