This year marks the 20-year milestone of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing, a landmark agreement in which Governments committed to “building a society for all ages”. The Madrid Plan of Action contains a broad range of objectives, including that of reducing poverty among older persons. Poverty is a particular risk for older persons. Most people work less or stop working altogether at some point in old age, either for health reasons, family responsibilities, because they must or want to retire at the statutory retirement age, or because discrimination undermines their employment opportunities. While many older persons remain productive, many of their contributions to their countries’ economies, to their communities and to their families are not formally recognized or paid. Their economic well-being depends on the availability of public income support, affordable health care, family support and savings to a greater extent than that of the working-age population. Because of the disadvantages they experience throughout their lives, older women may suffer from higher levels of poverty than old men.

This year marks the 20-year milestone of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing, a landmark agreement in which Governments committed to “building a society for all ages”. The Madrid Plan of Action contains a broad range of objectives, including that of reducing poverty among older persons. Poverty is a particular risk for older persons. Most people work less or stop working altogether at some point in old age, either for health reasons, family responsibilities, because they must or want to retire at the statutory retirement age, or because discrimination undermines their employment opportunities. While many older persons remain productive, many of their contributions to their countries’ economies, to their communities and to their families are not formally recognized or paid. Their economic well-being depends on the availability of public income support, affordable health care, family support and savings to a greater extent than that of the working-age population. Because of the disadvantages they experience throughout their lives, older women may suffer from higher levels of poverty than old men.  Although the challenges that older persons face are well recognized, the data necessary to assess them are not widely available. Despite the call made in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development for reliable data disaggregated by age and sex, among other characteristics, there are few cross-country comparable estimates of the prevalence of poverty among older men and women. The new set of relative poverty estimates by age and sex presented in this brief shows that old-age poverty is primarily a women’s issue.

Although the challenges that older persons face are well recognized, the data necessary to assess them are not widely available. Despite the call made in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development for reliable data disaggregated by age and sex, among other characteristics, there are few cross-country comparable estimates of the prevalence of poverty among older men and women. The new set of relative poverty estimates by age and sex presented in this brief shows that old-age poverty is primarily a women’s issue.

Applying a gender lens to old-age poverty

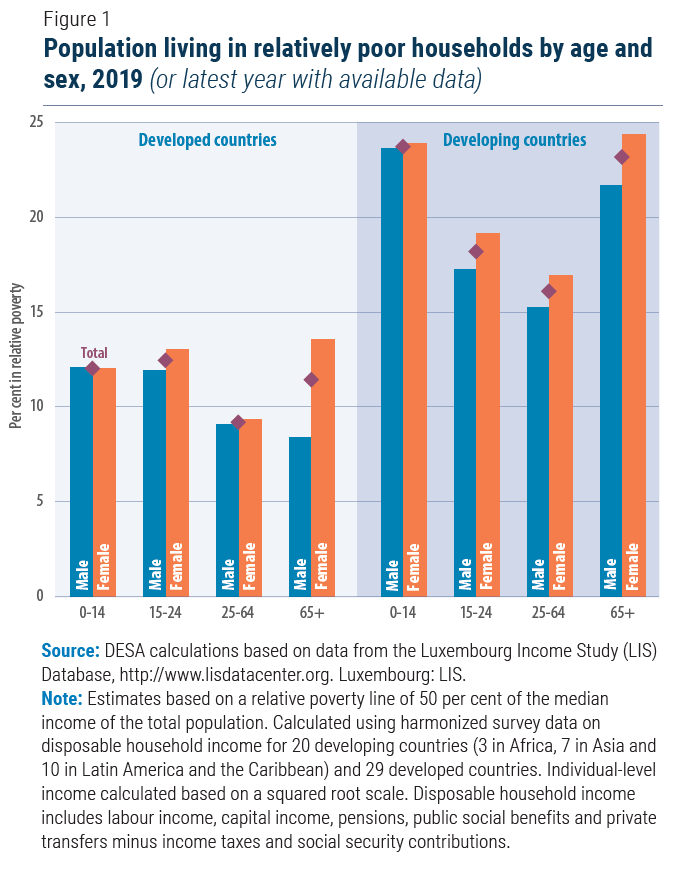

On average, persons aged 65 years or over live more often in relatively poor households than the working age population, as do children and youth (figure 1). Women suffer from higher levels of relative poverty than men at all ages, but the estimated gap is largest among older persons. In developed countries, the higher level of poverty in old age as compared to working ages is driven entirely by older women’s high poverty rates. In fact, older men enjoy lower levels of relative poverty than their younger counterparts in these countries. In the 20 developing countries with data, relative poverty is higher among older women than in any other of the groups shown in figure 1. There are several reasons behind the high levels of poverty among older women. Levels of formal labour market participation are lower among women than among men. In the labour market, lower wages and higher levels of informal employment lead to more economic insecurity among women in later life. While retirement benefits and old-age transfers should reduce old-age poverty, the gap in pensions between men and women is very large in countries with data. Because of the unequal distribution of care and domestic work, as well as their reproductive roles, women often have shorter working lives than men and therefore lower incomes from contributory pension programmes. While wealth plays an increasingly important role for economic security throughout old age, these labour market disadvantages and the unequal care burden affect women’s capacity to accrue wealth. Women also face legal obstacles. In 75 countries, women’s property rights are still restricted, for instance. Demography matters as well. Women live longer than men, on average. As a result of longer life expectancies, they are spending longer periods of time in retirement. Longer lives and age differences between spouses mean that older women are also more likely than older men to be widowed, less likely to remarry following widowhood and thus more likely to live alone—three features that contribute to their economic insecurity. Solitary living is more prevalent among older women than among older men in both developed and developing countries, although the overall percentage of older persons living alone is much higher in the former. In most developing countries, co-residence with adult children is still the most common form of living arrangement. These differences in household composition also have implications for the measurement of old-age poverty, as explained in Box 1.

Addressing the root causes of women’s old age poverty

High levels of poverty in old age are the result of the disadvantages that women experience throughout their lives. Preventing poverty and inequality from taking hold requires action at all stages of people’s life course. At the onset, any policy strategy to give all men and women an equal chance to age with health and economic security should promote equal access to opportunities. That is, it should aim towards giving all children the same chances to advance their capabilities from birth, including through access to health and quality education. As importantly, it should allow women and men to reap returns to education and lifelong learning through decent work and promote economic security in old age. Promoting decent work and investing in care services. Promoting women’s participation in formal employment and closing gender pay gaps require a transformative agenda on gender equality that goes well beyond labour market policies. After all, the world of work begins at home: women still perform three quarters of all unpaid and domestic work. Policies that ease the care burden within families, formally recognize care work and contribute to the sharing of domestic responsibilities between men and women will go a long way toward promoting women’s access to the labour market. In the labour market, promoting formalization of informal work is necessary to reduce working poverty and expand decent work opportunities for both men and women. Strong labour market institutions, from collective representation to wage policies, as well as comprehensive social protection systems, are necessary to ensure that work is performed with dignity and provides economic security. Wage regulations, including minimum wage and equal pay policies, are particularly important to promote gender equality and prevent poverty.  Ensuring equal rights for women and men. Labour market policies and social protection measures will have little impact on gender gaps in poverty if they are not complemented by measures to ensure equal access to land and credit, fair inheritance rights, full legal capacity and equal access to justice by women and men, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Globally, women are afforded three quarters of the rights enjoyed by men, on average, on a broad set of legal areas. Even where women enjoy equal rights, there is still a broad gap between laws and practice. Women still face social barriers to owning property, inheriting or moving and traveling independently, for instance, even in countries that do not impose legal barriers to their doing so. Improving the lives of older women and men through adequate pensions. In old age, pension systems play an important role in keeping people out of poverty. But the persistent disadvantages that women face limit their access to pensions and other social protection programmes around the world. Despite efforts to extend pension coverage, for instance, access to contributory pensions is usually limited to workers in the formal sector. With notable exceptions, people outside of the labour market as well as workers in informal employment and many workers engaged in casual forms of work do not have access to contributory pensions. There is no one-size-fits-all process to increase pension coverage, but action on two fronts can help. The first one is to encourage pension savings, including by promoting decent work opportunities and eliminating barriers to women’s participation, including older women. It is worth noting that the realization of the right to work and the adequate access to the labour market by older persons is considered a pre-requisite for dignity and living independently. The second one is to introduce and expand tax-funded pension schemes. Tax-funded pensions help ensure that all older women and men have at least a basic level of income security, particularly when they are universal in scope. They are typically designed as basic-income transfers meant to complement, rather than replace, contributory pensions. They do, however, have an impact on poverty alleviation among older persons. Encouraging the inclusion of workers in informal employment and those engaged in casual work in contributory schemes and improving financial literacy will also go a long way into promoting better pension coverage among women and other groups that suffer from disadvantages. However, the most pressing task is to provide paths to formalize informal employment and promote decent work. Not only will it contribute to expand pension coverage, but it will also help improve the adequacy of pension benefits, including by broadening and deepening contribution and tax bases. Whereas concerns over fiscal sustainability have dominated policy discussions related to pension systems and other social protection programmes, measures to ensure that expenditure is fiscally sustainable must not jeopardize the capacity of these systems to cover and provide economic security to all men and women, regardless of their labour market situation. In countries with comprehensive social protection coverage, the challenge is to ensure that all women and men receive adequate benefits. In some cases, the benefits received are inadequate to guarantee income security. In countries without comprehensive social protection systems, the focus must be on extending coverage, providing adequate benefits and creating fiscal space to finance social protection systems in order to meet target 1.3 of the SDGs. Unless all women and men have access to social protection at all stages of the life course, eradicating poverty will remain a distant goal.

Ensuring equal rights for women and men. Labour market policies and social protection measures will have little impact on gender gaps in poverty if they are not complemented by measures to ensure equal access to land and credit, fair inheritance rights, full legal capacity and equal access to justice by women and men, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Globally, women are afforded three quarters of the rights enjoyed by men, on average, on a broad set of legal areas. Even where women enjoy equal rights, there is still a broad gap between laws and practice. Women still face social barriers to owning property, inheriting or moving and traveling independently, for instance, even in countries that do not impose legal barriers to their doing so. Improving the lives of older women and men through adequate pensions. In old age, pension systems play an important role in keeping people out of poverty. But the persistent disadvantages that women face limit their access to pensions and other social protection programmes around the world. Despite efforts to extend pension coverage, for instance, access to contributory pensions is usually limited to workers in the formal sector. With notable exceptions, people outside of the labour market as well as workers in informal employment and many workers engaged in casual forms of work do not have access to contributory pensions. There is no one-size-fits-all process to increase pension coverage, but action on two fronts can help. The first one is to encourage pension savings, including by promoting decent work opportunities and eliminating barriers to women’s participation, including older women. It is worth noting that the realization of the right to work and the adequate access to the labour market by older persons is considered a pre-requisite for dignity and living independently. The second one is to introduce and expand tax-funded pension schemes. Tax-funded pensions help ensure that all older women and men have at least a basic level of income security, particularly when they are universal in scope. They are typically designed as basic-income transfers meant to complement, rather than replace, contributory pensions. They do, however, have an impact on poverty alleviation among older persons. Encouraging the inclusion of workers in informal employment and those engaged in casual work in contributory schemes and improving financial literacy will also go a long way into promoting better pension coverage among women and other groups that suffer from disadvantages. However, the most pressing task is to provide paths to formalize informal employment and promote decent work. Not only will it contribute to expand pension coverage, but it will also help improve the adequacy of pension benefits, including by broadening and deepening contribution and tax bases. Whereas concerns over fiscal sustainability have dominated policy discussions related to pension systems and other social protection programmes, measures to ensure that expenditure is fiscally sustainable must not jeopardize the capacity of these systems to cover and provide economic security to all men and women, regardless of their labour market situation. In countries with comprehensive social protection coverage, the challenge is to ensure that all women and men receive adequate benefits. In some cases, the benefits received are inadequate to guarantee income security. In countries without comprehensive social protection systems, the focus must be on extending coverage, providing adequate benefits and creating fiscal space to finance social protection systems in order to meet target 1.3 of the SDGs. Unless all women and men have access to social protection at all stages of the life course, eradicating poverty will remain a distant goal.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations