Achieving the transition to an environmentally sustainable and climate-safe future is a matter of justice in itself—people in vulnerable situations, poor countries and future generations stand to suffer the most from climate change and environmental degradation—but how it is done also matters. A green transition is already taking place, creating jobs and economic opportunities, and its potential in the medium—and long-term is much greater. Inevitably, however, a transformation on the scale necessary to contain climate change also implies losses of jobs, livelihoods, and public and private revenues in many areas and not necessarily where the benefits will accrue most directly. It also entails changes in the way energy and food needs are met and land is used, generating other types of social and environmental challenges. Breaking the inertial high-carbon development paths requires strong political support worldwide and at all levels. Greening strategies that do not take into account the political economy of the transition and the economic and social well-being of affected communities are therefore likely to be politically fragile and vulnerable to stalemates and reversals. In this context, calls for a just transition have been increasingly prominent in global, national and subnational policy circles.

Achieving the transition to an environmentally sustainable and climate-safe future is a matter of justice in itself—people in vulnerable situations, poor countries and future generations stand to suffer the most from climate change and environmental degradation—but how it is done also matters. A green transition is already taking place, creating jobs and economic opportunities, and its potential in the medium—and long-term is much greater. Inevitably, however, a transformation on the scale necessary to contain climate change also implies losses of jobs, livelihoods, and public and private revenues in many areas and not necessarily where the benefits will accrue most directly. It also entails changes in the way energy and food needs are met and land is used, generating other types of social and environmental challenges. Breaking the inertial high-carbon development paths requires strong political support worldwide and at all levels. Greening strategies that do not take into account the political economy of the transition and the economic and social well-being of affected communities are therefore likely to be politically fragile and vulnerable to stalemates and reversals. In this context, calls for a just transition have been increasingly prominent in global, national and subnational policy circles.  The concept of just transition is not new (see Box 1) but it gained traction internationally particularly since 2015, when it was referred to in the Paris Agreement, the ILO published its Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted, with the pledge of “leaving no one behind”. Numerous international commitments have been made and strategies have been, or are in the process of being, developed. In 2021, just transition was a central theme at COP26. In 2022, ahead of COP27, the concept is addressed in the priorities of the United Nations Secretary-General, in the IPCC report on Mitigation of Climate Change, and in the Ministerial Declaration of the 2022 High-Level Political Forum. A number of countries have references to and commitments for just transitions in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

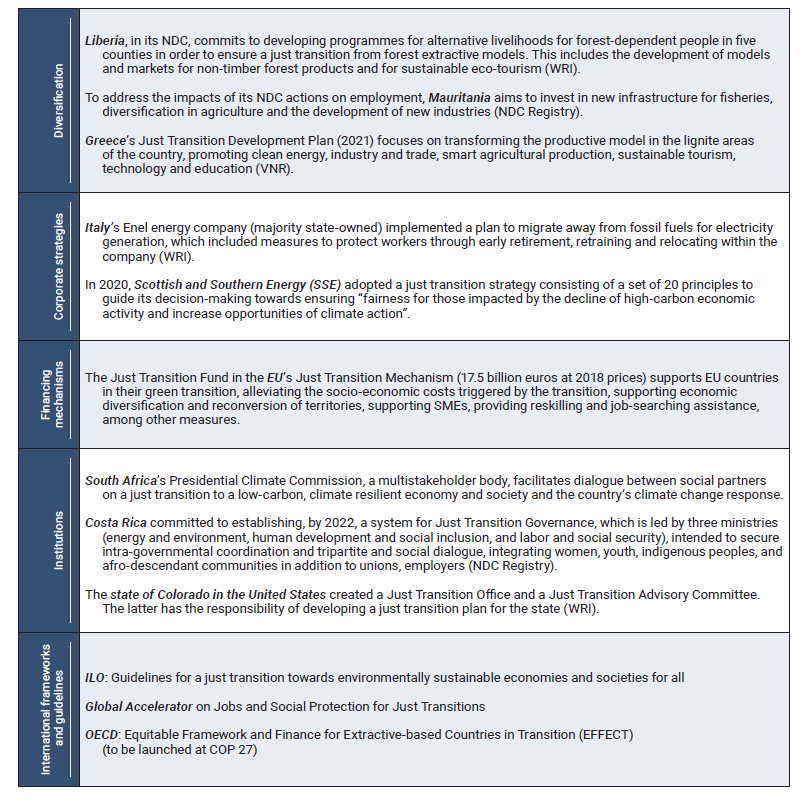

The concept of just transition is not new (see Box 1) but it gained traction internationally particularly since 2015, when it was referred to in the Paris Agreement, the ILO published its Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted, with the pledge of “leaving no one behind”. Numerous international commitments have been made and strategies have been, or are in the process of being, developed. In 2021, just transition was a central theme at COP26. In 2022, ahead of COP27, the concept is addressed in the priorities of the United Nations Secretary-General, in the IPCC report on Mitigation of Climate Change, and in the Ministerial Declaration of the 2022 High-Level Political Forum. A number of countries have references to and commitments for just transitions in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

What does just transition mean?

What does just transition mean?

Definitions differ, and there is widespread recognition of the importance of context-specific analysis and strategies, but just transition refers generally to strategies, policies or measures to ensure no one is left behind or pushed behind in the transition to low-carbon and environmentally sustainable economies and societies (the term has also been used in relation to other types of transitions, such as the transition to a digital economy, for example in the Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for Just Transitions launched by the UN Secretary-General in 2021). The origins of the concept lie in trade union activism, and the original emphasis was on addressing the loss of jobs resulting from the implementation of environmental regulations and policy. This remains a central element, but as more countries and a broader range of stakeholders have been engaged in understanding the challenges at hand and developing strategies for specific contexts, the definition of what a just transition consists of has expanded. When the ILO published its Guidelines in 2015, it defined just transition as “greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind”. The principles in its Guidelines refer, among others, to the need for social dialogue; respect, promotion and realization of rights at work; policies that address gender dimensions and promote the creation of decent jobs and provide social protection and skills development; and international cooperation. Approaches have varied in terms of how and to what extent they incorporate different dimensions of justice considered (distributive, procedural, and/or restorative (Newell and Mulvaney, 2013; Presidential Climate Commission, South Africa, 2022). They also vary in terms of the degree to which a green transition would be transformative in terms of justice or equity: from a status quo approach whereby job losses are compensated for, to approaches that imply a deeper transformation of political and economic systems, or that consider the shift to a low carbon future an opportunity to correct historical inequities or injustices (Just Transition Research Collaborative, 2018).

And in practice?

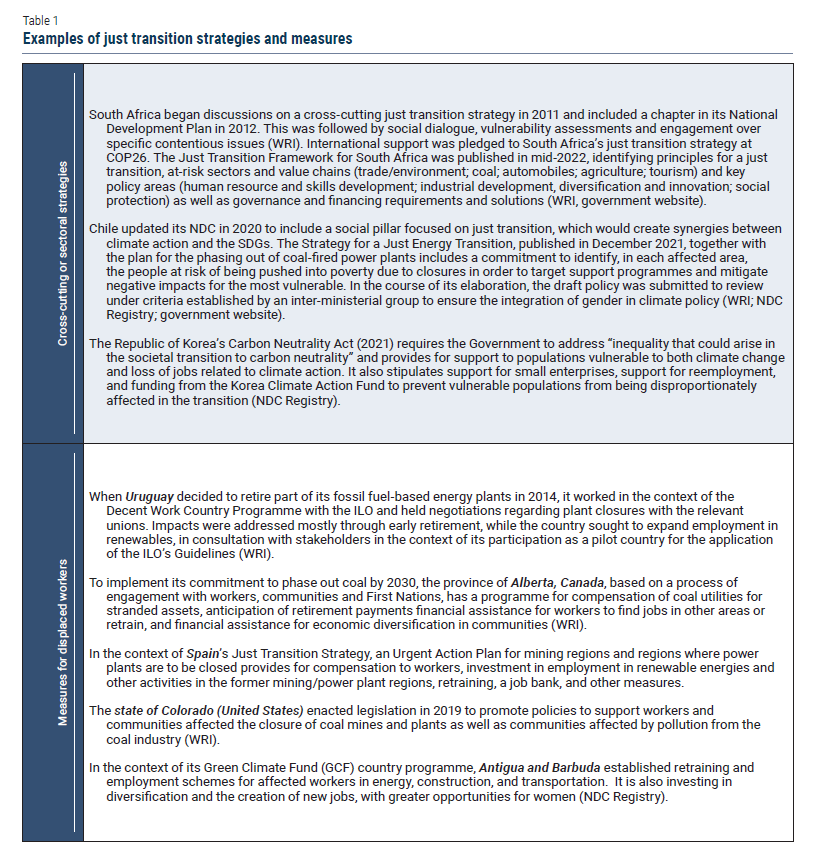

Policies for a just transition have included strategies to support workers and communities in specific areas, such as the state of Colorado in the United States, or the province of Alberta in Canada; sectoral policies at national level such as Chile’s Strategy for a Just Energy Transition; and cross-cutting national frameworks, such as the recently launched Just Transition Framework in South Africa (see Table 1 for examples). At the regional level, the EU’s Just Transition Mechanism includes funding and technical support to EU member states to “ensure that the transition towards a climate-neutral economy happens in a fair way”. There have also been corporate just transition strategies, though a review of action in the oil and gas, electricity and automotive manufacturing industries concluded that action has been limited so far (World Benchmarking Alliance, 2021). Consistent with the original concept, the main focus of many just transition policies has been to support workers and communities affected by the phasing out of polluting activities (frequently but not exclusively coal mining and coal-based energy plants) through temporary financial support and early retirement, employment services, training, business incentives, and support to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Krawchenko and Gordon, 2022). Securing diversification of economic activity in affected areas is an important component of strategies towards a just transition. It is also among the most complex and longstanding challenges, especially in developing countries (see, for example, CSIS and CIF, 2021 on the coal-dependent regions of Mpumalanga in South Africa and Jharkhand in India). Reflecting a broader concept of just transition, South Africa’s Framework for a Just Transition includes a commitment to restorative justice, which comprises “remedying past harms by building on, and enhancing, existing mechanisms such as equitable access to environmental resources, land redistribution and Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment” and addressing energy poverty. Other countries have reported on efforts to ensure that job creation in new (green) sectors is more equitable. For example, Antigua and Barbuda reports in its NDCs on efforts to ensure greater opportunities for women as they implement their Green Climate Fund (GCF) programme. Most of the discussion on just transition focuses on the move away from fossil fuels or other greenhouse-gas-generating activities such as practices that lead to deforestation, but the alternatives (the activities that are being “transitioned in”) and measures taken to adapt to climate change can also have social and environmental impacts for which just transition frameworks are as relevant (Atteridge and Remling, 2017; Atteridge et al., 2022; Institute for Human Rights and Business, 2021). Failure to identify and address environmental and social impacts of large-scale hydropower plants, for example, have generated conflict and in some cases proven ultimately unfeasible. Effective stakeholder engagement is broadly recognized as a core element of a just transition, both as a matter of procedural justice (fairness in decision-making) and as a means to identify the impacts that need to be addressed and feasible solutions. Reviews of experiences so far (Krawchenko and Gordon, 2021; Atteridge et al., 2022; WRI) highlight positive experiences but also shortcomings such as consultation processes that begin late in the game, are just pro forma, do not take into account local realities in terms of literacy, digital access and other elements, or face challenging political contexts. There is no blueprint for a just transition, but the growing body of experience can provide important references for the development of context-appropriate processes, strategies and solutions.

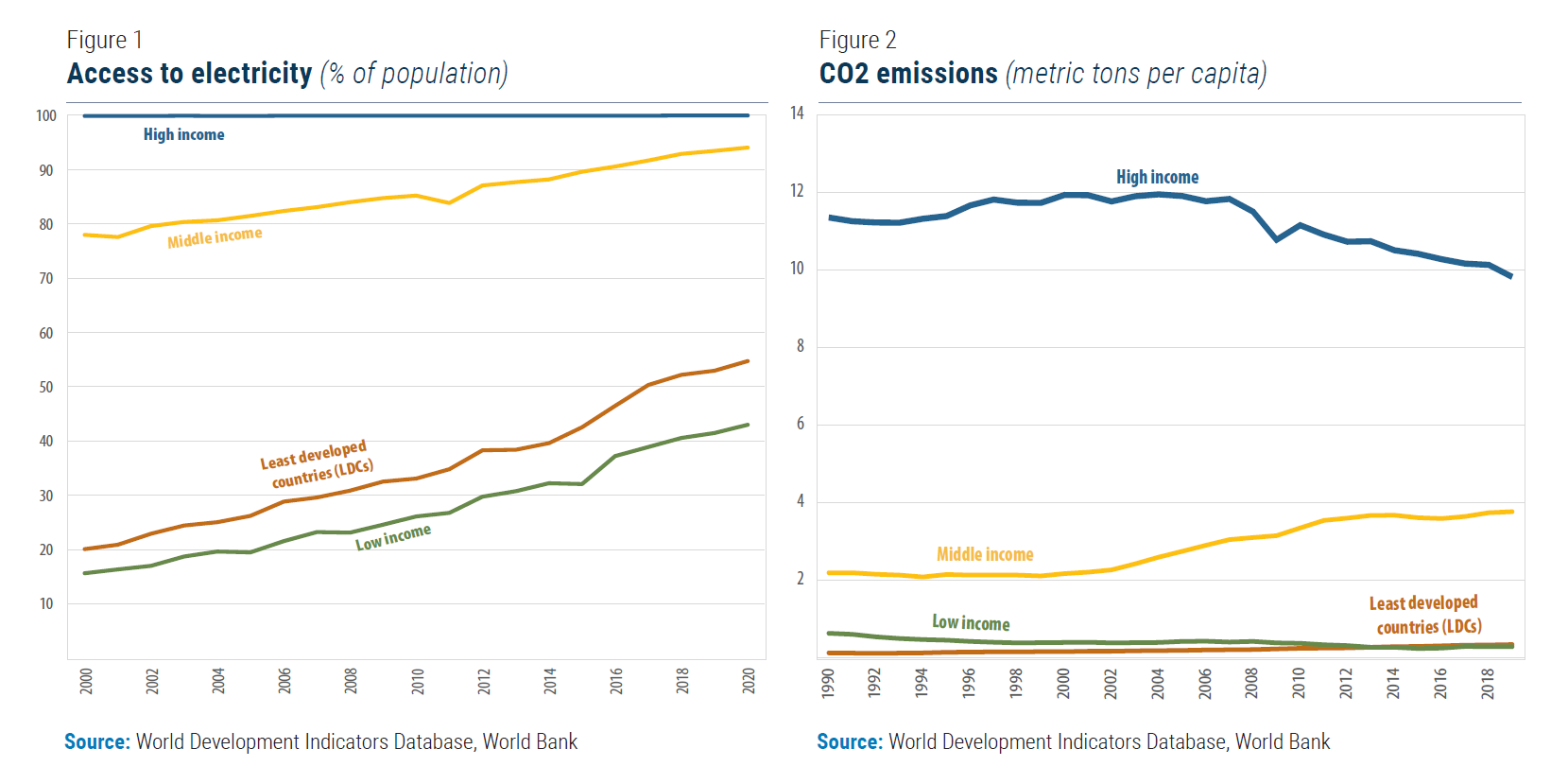

A globally just transition

While securing just transitions is a challenge for countries at all stages of development, developing countries face distinctive difficulties. Abdenur (2022) identifies factors that define the context for a just transition in middle-income countries (MICs). Relative to high-income countries, MICs face high poverty rates; informality; young populations and high dependency ratios; reliance on single commodities; distinct ecological and climate challenges; limited access to capital; and limited institutional capacity, among others. These characteristics apply in even greater measure to low-income countries, where policymakers face particularly limited fiscal resources compared to pressing social demands (including the need to expand access to electricity—see Figure 1—and invest in adaptation and climate resilience) while having marginal contributions to global emissions (Figure 2). Many developing countries also face significant challenges in terms of their productive capacities and their ability to diversify economic activity. Several, including a number of least developed countries (LDCs), rely on fossil fuels as an important source of energy and fiscal revenue, and some are just starting to reap the benefits of investments in their reserves. The concept of just transition cannot be dissociated from global climate justice and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. In addition to the fulfillment of climate action and climate financing commitments, a globally just transition requires support for developing countries’ transition paths (including just transition strategies) in ways that take their realities in terms of capacities and needs into account (see Walsh et al., 2022 for one perspective on what this could mean for Africa). It also requires that countries consider and address the impacts of their own greening strategies on other countries, avoiding the creation of trade barriers and the exclusion of developing countries from opportunities in nascent value chains (CDP, 2022).

References

Abdenur, Adriana (2022), “Stockholm+50: What does Just Transition mean for Middle Income Countries”, op-ed, United Nations Climate Action, 31 May. http://voice.marketingbangkok.net/en/climatechange/what-does-just-transition-mean-middle-income-countries Atteridge, A. S. et al (2022). “Exploring Just Transition in the Global South”. Climate Strategies. https://climatestrategies.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Exploring-Just-Transition-in-the-Global-South_FINAL.pdf Atteridge, A.S. and Elise Remling (2017), “Is adaptation reducing vulnerability or redistributing it?”, WIREs Climate Change, Volume 9, January/February 2018. CDP (Committee for Development Policy) (2022), “Report on the twenty-fourth session (21-25 February 2022). E/2022/33. http://undocs.org/en/E/2022/33 Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and Climate Investment Funds (CIF) (2021), “Understanding Just Transitions in Coal-Dependent Communities”, Just Transition Initiative. https://justtransitioninitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/CoalDependentCommunities_Report.pdf ILO (2015), “Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all”, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—-ed_emp/—-emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_ 432859.pdf Institute for Human Rights and Business (2021), “What is Just Transition?”, https://www.ihrb.org/explainers/what-is-just-transition. Just Transition Research Collaborative (2018), “Mapping Just Transition(s) to a Low-Carbon World”. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, University of London Institute in Paris. https://cdn.unrisd.org/assets/library/books/pdf-files/report-jtrc-2018.pdf Krawchenko, T.A. and M. Gordon (2021) “How Do We Manage a Just Transition? A Comparative Review of National and Regional Just Transition Initiatives.” Sustainability 2021, 13,6070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116070 Newell, Peter and Dustin Mulvaney (2013), “The political economy of the ‘just transition’, The Geographical Journal, vo. 179, No. 2, June 2013, pp. 132-140, doi: 10.1111/gioj.12008. Presidential Climate Commission, South Africa (2022), “A Framework for a Just Transition in South Africa”, https://pccommissionflow.imgix.net/uploads/images/A-Just-Transition-Framework-for-South-Africa-2022.pdf Walsh, Gareth, Imad Ahmed, Jonathan Said, Martim Faria e Maya (2021), “A Just Transition for Africa: Championing a Fair and Prosperous Pathway to Net Zero”, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. https://institute.global/advisory/just-transition-africa-championing-fair-and-prosperous-pathway-net-zero World Benchmarking Alliance (2021), “2021 Just Transition Assessment” https://www.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/research/2021-just-transition-assessment/ World Resources Institute (WRI) Just Transition and Equitable Climate Action Resource Center. https://www.wri.org/just-transitions

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations