The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in significant output contractions, deteriorating social conditions and worsened debt sustainability. Some countries that had previously attained higher income status and deemed no longer to need grants and concessional finance in the form of Official Development Assistance (ODA) are once again in need of heightened international support. This includes countries that slid back to a lower income category as well as higher income vulnerable countries, such as numerous small island developing States (SIDS), who have found it difficult to respond and recover from the pandemic without support. Access to ODA, including through concessional finance windows at multilateral development banks (MDBs), is generally linked to gross national income (GNI) per capita. As developing countries attain higher income per capita status, access to grants and concessional windows declines. As a result, countries’ average cost of borrowing generally becomes more expensive, with shorter maturities, which can widen financing gaps in normal times. In times of crises, these gaps are magnified, underscoring countries’ need for support. Recognition that the need for support is often linked to factors that are not measured by income has led to MDBs, in particular, to include important exceptions in eligibility criteria, including incorporating vulnerability. However, it has often been ad hoc and not based on a full analysis of risk factors. This policy brief outlines the criteria to access ODA, why it needs to improve and suggests a way forward.

The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in significant output contractions, deteriorating social conditions and worsened debt sustainability. Some countries that had previously attained higher income status and deemed no longer to need grants and concessional finance in the form of Official Development Assistance (ODA) are once again in need of heightened international support. This includes countries that slid back to a lower income category as well as higher income vulnerable countries, such as numerous small island developing States (SIDS), who have found it difficult to respond and recover from the pandemic without support. Access to ODA, including through concessional finance windows at multilateral development banks (MDBs), is generally linked to gross national income (GNI) per capita. As developing countries attain higher income per capita status, access to grants and concessional windows declines. As a result, countries’ average cost of borrowing generally becomes more expensive, with shorter maturities, which can widen financing gaps in normal times. In times of crises, these gaps are magnified, underscoring countries’ need for support. Recognition that the need for support is often linked to factors that are not measured by income has led to MDBs, in particular, to include important exceptions in eligibility criteria, including incorporating vulnerability. However, it has often been ad hoc and not based on a full analysis of risk factors. This policy brief outlines the criteria to access ODA, why it needs to improve and suggests a way forward.

ODA plays a key role in financing for sustainable development

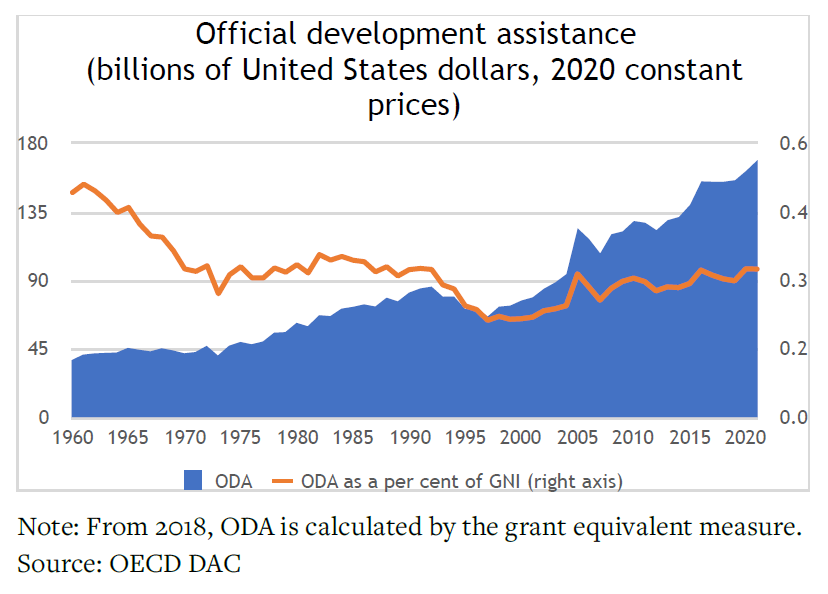

ODA is well recognized for its role in supporting developing countries and is a countercyclical resource in times of crisis. It has been a component of the global COVID-19 response, with development providers increasing ODA to an all-time high of $179 billion in 2021, an important lifeline for the poorest and most vulnerable countries to respond to the pandemic and resulting economic crisis. Collectively, donors continue to fail to meet ODA commitments to provide 0.7 per cent of ODA per GNI and allocate 0.15-0.20 per cent of GNI to least developed countries (LDCs). ODA is also not keeping pace with the heightened demand from the pandemic, as well as from the climate crisis and impact from the war in Ukraine. In the 2022 Financing for Sustainable Development Report, the Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development urged ODA providers to scale up and meet their ODA commitments with new and additional resources, including for LDCs.

Income per capita dominates but vulnerability metrics are increasingly incorporated

Income per capita dominates but vulnerability metrics are increasingly incorporated

With demand perennially outstripping supply, it is important that ODA resources reach those that need it the most. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda recognized ‘the importance of focusing the most concessional resources on those with the greatest needs and least ability to mobilize other resources.’ GNI per capita has long been used to identify countries with the most needs, and it is the key metric in the allocation of aid. As countries achieve higher income per capita levels, they are deemed to no longer need ODA and “graduate”. In the context of international development cooperation, “graduation” refers to three separate events, including graduation from: i) ODA eligibility; ii) multilateral concessional assistance, particularly concessional windows at multilateral development banks (MDBs); and (iii) LDC status. A key determining factor of all three contexts is a country’s per capita income, although other factors are also considered. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) list of ODA recipients show all countries and territories that are eligible to receive ODA. Graduation from the DAC ODA list is based on income per capita alone. Graduation from multilateral concessional assistance is based primarily on per capita income along with creditworthiness. MDBs have, however, increasingly incorporated elements of vulnerability to allow access to their concessional windows. Graduation from LDC status is based on a broader set of criteria, including income per capita, vulnerability, and the level of human assets. Countries that exceed the high-income threshold ($12,695 in 2020) for three consecutive years are removed from the OECD DAC list. When a country graduates from the DAC ODA list, financing it receives is not reported in official ODA statistics. However, ODA graduates can and do receive concessional support, albeit to varying degrees. For instance, despite graduating from the DAC ODA list, Palau still has access to a blend of concessional and regular loans from the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Countries that have graduated from the OECD DAC list also continue to access the European Development Fund, which uses an economic vulnerability index in its country allocations formula. The OECD DAC also has in place a process of reverse graduation – countries are reinstated for ODA eligibility if their per capita income falls back below the high-income threshold for one year. This was the case for Panama, which was scheduled to graduate in 2022 but was reinstated on the ODA list due to a fall in income per capita following the COVID-19 crisis. Funding allocations in concessional windows of MDBs are determined both by need – defined by per capita income – and by policy performance and institutional capacity, based on the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) (with countries with higher CPIAs and stronger institutions, receiving more). The World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) graduation process starts when per capita income exceeds an operational cut-off, at $1,205 for 2022. While the graduating country is no longer eligible for IDA grants, it generally continues to receive ODA from bilateral donors well after graduation, albeit with more expensive terms of finance. However, several exceptions exist, reflecting an acknowledgement of the impact of vulnerability on development. The small island exception, which has been in place since 1985, allows small island economies (populations less than 1.5 million) continued access to IDA even with higher incomes. In 2017, this was extended to IDA-eligible small States, which benefited Bhutan, Djibouti, Guyana and Timor-Leste. In 2019, this was further extended to small island economies based on vulnerability along with income and creditworthiness criteria, which benefited Fiji. An exceptional allowance was also made to Jordan and Lebanon in response to the Syrian refugee crisis. The IDA Crisis Response Window (CRW) and regional programme during the 19th replenishment (IDA19) provide additional resources to help eligible countries respond to severe economic crises as well as major humanitarian and climatic disasters. Several regional development banks’ concessional facilities (e.g., ADB and the Caribbean Development Bank) also include exceptions that allow SIDS to access concessional funding even if they exceed income thresholds. Although some bilateral donors tend to prioritize their support towards LDCs, LDC graduation has not generally had a direct impact on concessional financing flows. LDCs are also generally not explicitly targeted for multilateral concessional assistance. Exceptions are the ADB, the European Development Fund and Green Climate Fund, which prioritizes LDCs. LDCs also have access to the Least Developed Country Fund (LDCF) managed by the Global Environment Facility, which was set up in 2001 to support LDCs in climate change adaptation.

The covid-19 crisis is spotlighting the need for change

The pandemic has already influenced the graduation and country classification decisions of major MDBs and the OECD DAC. For example, fewer counties are expected to graduate from IDA by 2032, compared to pre-COVID estimates, as the pandemic has adversely impacted the income of countries, increased debt risks and worsened social and institutional conditions. The ADB reclassified Fiji due to the impact of COVID-19 to benefit from a blend of concessional and non-concessional finance. The DAC exceptionally agreed to delay the graduation of Antigua and Barbuda, Palau and Panama from the DAC List of ODA Recipients for one year. Only Antigua and Barbuda and Palau graduated on 1 January 2022. The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the limitations of focusing on income per capita to channel aid to countries that need it the most, underscoring the need for longer-term focused risk-informed ODA allocation. This entails accounting for the range of risks that graduated countries may still encounter to ensure a smooth and sustainable transition from requiring international support. SIDS, in particular, have reiterated calls for the use of multidimensional vulnerability as criteria to access concessional finance amid the COVID-19 crisis. SIDS are some of the most vulnerable countries, particularly to natural hazards and climate change, and have been severely affected by the COVID-19 crisis. They are also sensitive to the impacts of graduation in all contexts: from ODA eligibility, multilateral concessional assistance, and LDC categorization.

Donors should use multidimensional vulnerability criteria in a consistent and systematic way

While the multidimensional vulnerabilities of countries are increasingly considered by donors, their responses have largely been reactive to date. At a time when risks are escalating and the world faces ever more crises and challenges, there is need for a more consistent, long-term focused, and systematic way to account for multidimensional vulnerabilities. Donors should aim to mainstream vulnerability criteria in their allocation decisions by using vulnerability metrics as a standard complementary measure to income per capita. A few MDBs already have this in place – this should be replicated through the network of public development banks. The OECD DAC should also expand criteria for the ODA list to include vulnerability criteria, alongside income per capita. The recent agreement by the United Nations General Assembly to develop a multidimensional vulnerability index (MVI) provides an opportunity for countries to better communicate vulnerabilities through a straightforward indicator. Global acceptance of the MVI as the pre-eminent measure of assessing vulnerability could lead to application of the MVI by donors as a complementary criterion to income per capita. It could also be used more broadly, for example, in debt sustainability assessments. However, as with the experience of current vulnerability indices, some countries will not be classified as highly vulnerable, while others may qualify, which should not impact current access to concessional finance for those in need. Hence, it is imperative that donors increase the volume of ODA with new and additional resources, which together with a consistent and systematic use of vulnerability criteria can help ensure that ODA reaches the countries that need it the most.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations