Introduction

Introduction

Over the last two years, the world economy has been rocked by multiple non-economic shocks, from the COVID-19 pandemic to the war in Ukraine. Climate-related disasters continue to increase in frequency and severity. Together, these events have had enormous socio-economic consequences due to the interrelated nature of economic, social and environmental risks. But not all countries and people have been impacted in the same way, in part because a financing divide is sharply curtailing the ability of many developing countries to respond to shocks and invest in recovery. The outbreak of COVID-19 delivered a seismic shock to the global economy, but developed countries were able to respond with aggressive macroeconomic policies. They financed massive response packages (worth 18 percentage points of GDP) at very low interest rates, stabilizing household incomes and financial markets. Developing countries lacked the resources for a response at similar scale, despite international support. Middle-income countries generally had supportive fiscal policy, but at a smaller scale than in developed countries. The poorest countries, most of whom were shut out of markets or faced very high borrowing costs, were forced to cut spending in areas critical to the SDGs, including education and infrastructure, as they faced shortfalls in revenues at a time of greater needs. On the monetary policy side, while many developing country central banks lowered interest rates and reserve requirements, their interventions were smaller in scale and shorter in duration, due to concerns over currency depreciations, inflation and capital outflows. This more limited response, along with inadequate vaccine availability, has led to a more protracted crisis in developing countries, with differences projected to persist in the medium term. Even before taking the fallout from the war in Ukraine into account, one in five developing countries was projected to not reach 2019 per capita income levels by the end of 2023; unmet financing needs for key SDG sectors are projected to have increased by 20 per cent.2 Total investment rates in developing countries are not projected to return to pre-pandemic levels over the next two years. A subdued investment recovery contrasts sharply with the significant scale up in public investment needed to meet climate objectives and the SDGs. Such SDG investments require access to long-term and affordable financing.  Yet, many of the poorest countries are in no position to finance this investment push. Public debt has reached critical levels. At the beginning of 2022, 3 in 5 of the poorest countries are at high risk or already in debt distress, one in four middle-income countries are at high risk of fiscal crisis. Since late February, and due to the fallout from the war in Ukraine, rising energy and food prices put additional pressures on fiscal and external balances of commodity importers. Sharply tightening global financial conditions are already visible in rising credit spreads. Risks of a systemic crises affecting multiple developing countries have risen further.

Yet, many of the poorest countries are in no position to finance this investment push. Public debt has reached critical levels. At the beginning of 2022, 3 in 5 of the poorest countries are at high risk or already in debt distress, one in four middle-income countries are at high risk of fiscal crisis. Since late February, and due to the fallout from the war in Ukraine, rising energy and food prices put additional pressures on fiscal and external balances of commodity importers. Sharply tightening global financial conditions are already visible in rising credit spreads. Risks of a systemic crises affecting multiple developing countries have risen further.

Costs and terms of capital in developing countries

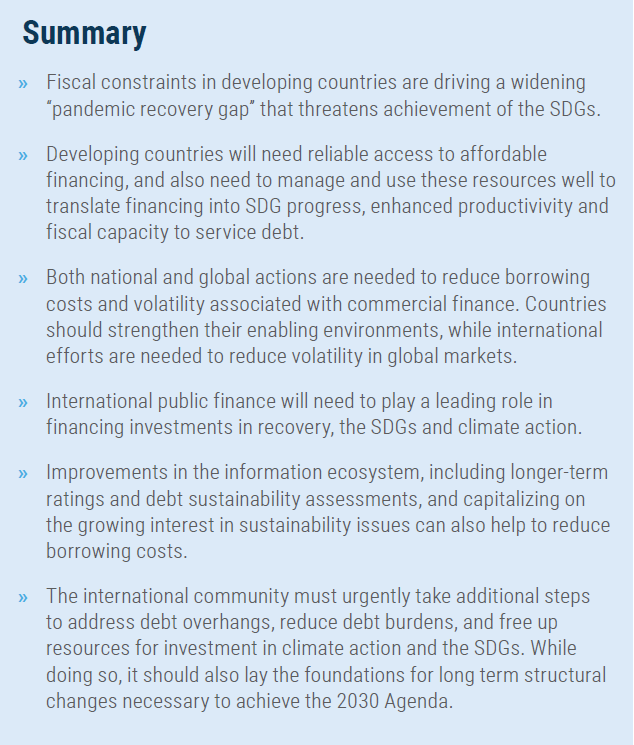

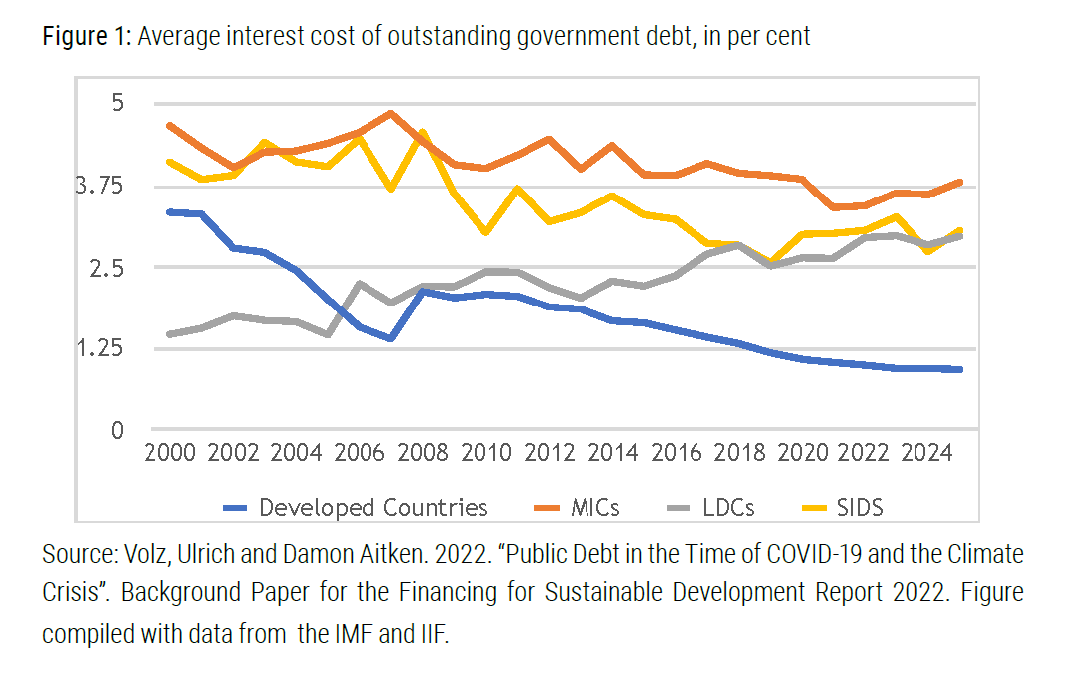

Developing countries typically face relatively high borrowing costs, with their average interest expense on debt three times higher than in developed countries (Figure 1). In the low interest environment of the last decade, the average interest cost of outstanding sovereign debt in developed countries fell to around 1 per cent. Least developed countries (LDCs), which have access to concessional lending, have increasingly tapped international markets in recent years, often at rates of over 5 or even 8 per cent. This has dragged up their average borrowing cost, worsened their debt dynamics, and translated into less fiscal space: LDCs dedicate 14 per cent of their domestic revenue to interest payments compared to only around 3.5 per cent on average in developed countries, despite the latter’s much larger debt stocks (Figure 2).  Fiscal space is also more limited in many developing countries because debt sustainability concerns tend to arise at lower levels of debt than in developed countries, translating into higher risk premia and borrowing costs. While many developing countries have reduced reliance on foreign currency borrowing in recent years, many still face difficulty issuing long-term debt domestically. Yet, foreign currency borrowing can be expensive. Over the last 200 years, the average annual return of foreign currency debt to investors has been around 7 per cent, after accounting for losses from defaults. This exceeded the “risk free” return on US and UK bonds by an average of 4 percentage points. Since the start of the emerging market ‘bond finance era’, around 1995, total returns to investors (net of losses from defaults) have been even higher, averaging almost 10 per cent – a historical high, with a credit spread of around 6 percentage points over the risk-free rate. Foreign currency bonds thus more than compensate investors for the risks they face, even through a period of repeated financial turmoil in developing countries. Indeed, external sovereign bonds have been the best performing asset class, outperforming other asset classes such as equities or corporate bonds over this period. These high investor returns equate to high borrowing costs for countries, thus diverting government expenditures to debt servicing. The dependence of many developing countries on foreign savings and foreign currency borrowing is not only expensive in terms of interest costs, it also makes countries vulnerable to the global financial cycle and sudden stops. Together with often less well-anchored inflation expectations, this limits their monetary policy space as well.

Fiscal space is also more limited in many developing countries because debt sustainability concerns tend to arise at lower levels of debt than in developed countries, translating into higher risk premia and borrowing costs. While many developing countries have reduced reliance on foreign currency borrowing in recent years, many still face difficulty issuing long-term debt domestically. Yet, foreign currency borrowing can be expensive. Over the last 200 years, the average annual return of foreign currency debt to investors has been around 7 per cent, after accounting for losses from defaults. This exceeded the “risk free” return on US and UK bonds by an average of 4 percentage points. Since the start of the emerging market ‘bond finance era’, around 1995, total returns to investors (net of losses from defaults) have been even higher, averaging almost 10 per cent – a historical high, with a credit spread of around 6 percentage points over the risk-free rate. Foreign currency bonds thus more than compensate investors for the risks they face, even through a period of repeated financial turmoil in developing countries. Indeed, external sovereign bonds have been the best performing asset class, outperforming other asset classes such as equities or corporate bonds over this period. These high investor returns equate to high borrowing costs for countries, thus diverting government expenditures to debt servicing. The dependence of many developing countries on foreign savings and foreign currency borrowing is not only expensive in terms of interest costs, it also makes countries vulnerable to the global financial cycle and sudden stops. Together with often less well-anchored inflation expectations, this limits their monetary policy space as well.

A multifaceted policy response

The challenge is to increase access to long-term, affordable and stable financing, and to use proceeds productively so that public policy goals are achieved and fiscal capacity is enhanced, while addressing debt distress when necessary. On the right terms, debt financing can enable countries to respond to emergencies and fund long-term investments, including in climate action and the SDGs. Productive investments in turn enhance growth and fiscal capacity, thus generating the resources to service debt sustainably. For countries with large debt overhangs on the other hand, additional lending can be counterproductive, and debt relief and more grant financing indispensable. The 2022 Financing for Sustainable Development Report puts forward recommendations in four areas to bridge the ‘great finance divide’.

Improving access to international public finance

First, access to additional long-term affordable international public financing, especially concessional financing, is critical. First, ODA commitments must be met, including provision of grant finance. Second, public development banks should play a greater role. They can lend long term at affordable rates. They can also lendcountercyclically, easing financing pressures during crises. Multilateral development banks can further expand their lending through balance sheet optimization; their shareholders should also support capital increases. As prescribed holders of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), multilateral development banks (MDBs) can also be a vehicle for advanced economies to channel their unused SDRs. MDBs themselves can further improve lending terms, for example through ultra-long term loans, and systmatic use of state-contingent clauses in their own lending, to automate standstills for countries in crisis situations. The entire ‘system of development banks’ should also be strengthened, including through co-financing and risk sharing (which can help the system take advantage of diversification across the system). In addition multilateral and regional development banks can extend capacity support to national institutions; international development banks can, in turn, benefit from national banks’ detailed knowledge of local markets.

Enhancing terms of market financing

Second, steps must be taken at national and international levels to improve borrowing terms that developing countries face in international financial markets. First and foremost, this includes domestic measures to reduce risks by strengthening institutions and improving enabling environments. In addition, by increasing domestic savings and strengthening domestic capital markets, countries can also reduce reliance on foreign borrowing over time. Global sources of risk have become more dominant drivers of volatlity of capital flows. Capital account management measures can help mitigate the adverse impact of tighter global financial conditions, but developed countries should also aim to reduce global risks. For example, major central banks should be cognizant of the spillover effects of their monetary policy decisions on other countries, also because ‘spillbacks’ have become more impactful in a more integrated global financial system; prudential regulations can reduce short-term leverage in the system; and the global financial safety net should be further strengthened. Uncertainty premia that drive up sovereign borrowing costs can also be reduced by enhancing transparency and strengthening the broader information environment. For example, further extending the horizon of credit ratings (which are often only for up to 3 years) and debt sustainability assessments would provide insights for long-term oriented investors. The use of scenarios and probabilistic approaches could help to more systematically consider long-term economic and non-economi risks and other factors.4 More systematic valuations of public assets and balance sheets would increase policy makers’ awareness and could lead to more effective use of such assets, generate additional income, and provide investors with a better understanding of government net worth. In addition, some investors may be willing to pay a premium for debt instruments that tie the use of proceeds to SDG and climate priorities. A growing number of sovereigns have issued green, social and sustainability bonds; development finance institutions could consider partial guarantees and other credit enhancements for such policy-based bonds.

Addressing debt overhangs

Third, the international community needs to step up efforts to resolve unsustainable debt situations urgently and speedily. High levels of debt mean that additional financing alone will not suffice, and could make the problem worse for some countries. Measures to address the debt overhang must be part of global efforts. The Common Framework adopted by the G20 and Paris Club is a step forward, as it allows, for the first time, for coordination of all major bilateral creditors. But implementation has been extremely slow, many highly indebted countries are ineligible, and the mechanisms to incentivize commercial creditor participation are weak. These implementation challenges must be addressed urgently, e.g. by providing greater clarity on processes and timelines, expanding access to middle-income countries, providing a standstill on debt service during negotiations, and strengthening tools and mechanisms to enforce comparability of treatment of private sector creditors. As a systemic crisis has become more likely in the aftermath of the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, more effective mechanisms for debt relief will likely be needed, including to bring in commercial creditors. Legislative instruments could be considered, either by actions in key jurisdictions or at the international level. Such actions would limit the ability of holdout creditors to recover claims, or immunize sovereign assets from their judicial actions. These and more wide-reaching improvements to the international financial architecture should be discussed in an inclusive forum that brings together creditors and debtors, and hence within the United Nations.

Using proceeds effectively and aligned with the SDGs

Fourth, countries must ensure that all financing is aligned with the SDGs and climate action, and used well. For additional financing to translate into positive long-term outcomes, resources have to be used well, and risks carefully managed. Access to more – and more diverse – sources of debt financing increases the burden on debt managers to carefully and transparently manage risk. Lenders also have a responsibility to lend in a way that does not undermine a country’s debt sustainability, including for due diligence to assess a sovereign borrower’s capacity to service loans. In terms of use of proceeds, the efficiency of public investment is a key determinant of its growth and debt sustainability impact. Evidence suggests that public investment efficiency gaps are sizeable in many countries, with more than one third of resources lost in the public investment process on average. Public investment decisions must also be guided by a country’s medium-term sustainable development strategies and plans, and fully aligned with the SDGs. Linking public investment decisions to a medium-term fiscal and budget framework and debt management strategy can reduce the volatility of financing for capital expenditure. Stronger medium-term budget practices are associated with higher and less volatile public investment performance. Integrated National Financing Frameworks can help countries to align their investment strategies and related financing decisions with their overall development plans.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations